By Anton Mukhamedov

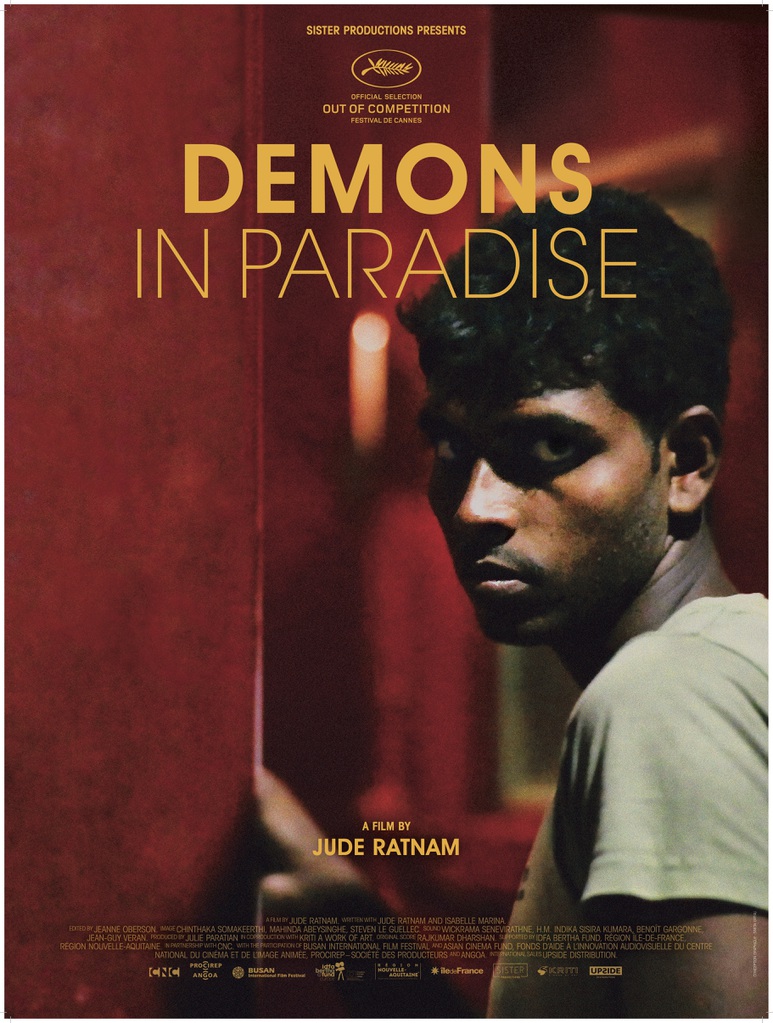

34 years after the eruption of a civil war in Sri Lanka waged by the majority-Sinhalese government against the Tamil Tigers, activist and filmmaker Jude Ratnam directed Demons in Paradise, a documentary going back to the roots of a brutal conflict by exploring the variety of memories it has produced. During the 2017 edition of the film festival War on Screen, I had the chance to interview Jude about what documentary cinema meant to him.

A.M. Film-making isn’t your principal vocation, as you started with humanitarian work. Still, you bring both imagination and innovative filming techniques to the field, so how did such a transition occur?

Jude Ratnam: I fell into the making of this movie quite by accident, partly because of Charlie Chaplin. When I saw Modern Times, I was 25 years old and the civil war was going on in Sri Lanka. I was disillusioned with my work. Modern Times was eye-opening. I realised how powerful cinema could be.

It is in the process of filming that I discovered the whole tradition of documentary film-making, especially the work of Claude Lanzmann. As I started Demons in Paradise, I realised I hadn’t prepared myself. I had an idea of what I wanted to do, but hadn’t meticulously prepared myself. The form emerged on the field.

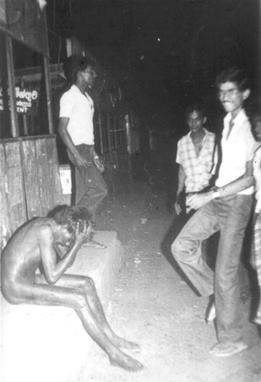

There’s a very striking scene at the beginning of your documentary, when you interview a journalist who took a photo of a Tamil man being killed during the riots. You ask him if he has any regrets about not having acted… Is your film a way to act?

During the film, I was struggling with this whole question of “how can someone make a picture of a man being killed?” As I finished, I understood the whole process of art itself: it cannot intervene directly in human affairs. Yet, somehow, it also exists there as a witness to look upon everything. As a way to relieve yourself from this horrible past: one fundamental purpose of art is the release it brings. Instead of a static, detached sense of admiration, art has to be able to offer something of a use, like an Aristotelian cathartic moment.

It seems that this is even less a documentary about war than a documentary about people remembering war, about the memories…

Initially, it was supposed to be very didactic. I wanted to explain what was going on, the brutality of the past. It turned into much more about the ‘you’ in the domain of history. And then you start asking those basic fundamental questions of existence itself. I think it’s what probably also allowed me to unconsciously play with the traditions of the genre, like blurring the boundary between the past and the present. You don’t know if the characters are in the past or in the present. Is the reality we see the true reality? We can’t give it a concrete definition.

Speaking of the title, what is your conception of a paradise?

For me, paradise is here and now instead of a utopian place that we have to reach. We’re already in paradise. It’s up to us to realise that. In that, we’re obstructed by the demons.

And your film helps to exorcise these demons, such as the colonial past of Sri Lanka?

No, you cannot exorcise the demons completely.

In the flux of human history, we struggle to become more human. It’s the story of becoming, as being human is the opposite of being ossified. If you try to exorcise the demons completely, they turn into something even more horrific, like an attempt to purify an ethnic group or country or religion, which is also an attempt to ossify. This is the whole difficulty of the human condition.

The first part of my film seemed to be about trying to justify the struggle of the Tamil Tigers, but what it turned into at the end is asking those basic questions about identity. These are the questions I grappled with.

The more you’re able to connect to the ground you’re standing on, in a metaphorical sense, the more the world opens up to you. If fear clogs you and closes your mind, the entire world turns dark. But the more you go look deeper within yourself, the more you realise how you connect deeply to other beings. You cannot escape these limits cognitively, as it’s impossible to connect to the cosmos through your own rationality. It’s an emotional process, something which happens through contemplation.

If you try to exorcise the demons completely, they turn into something even more horrific, like an attempt to purify an ethnic group or country or religion, which is also an attempt to ossify.

So you travel deeper into your soul and it’s strange that you do it emotionally, but suddenly people can identify with the art you make and relate not just emotionally but also cognitively. And then it becomes a rational attempt to resolve something that’s gone wrong.

This is the great thing about art, philosophy and religion, as well as the reason they’re all connected. The only difference between philosophy, mysticism and art is that the first two don’t involve craft.

In a certain way, the discourse on religion in Demons in Paradise might be a response to the whole debate on radicalism in religion?

Religion? Not at all, I don’t like to use these words, it puts me in trouble… But the problem lies within reading the text in a literal and structural way. The moment you start reading it in a metaphorical sense, a new world open up. It’s something greater than you and has been there for a long time. Meanwhile, at least in my film, people also want to live in a historical, factual, material sense.

And the moment you start using the word “atheist” or “agnostic”, people start putting you into categories and you become that and only that.

Since we’re talking about identity, you’ve spent ten years on Demons in Paradise. Are you going to continue producing movies?

Film-making is inseparable from you. I think I fell in love and now I cannot part with it. But whether I’ll go on to make more films, this is contingent: only life can tell. You cannot make issue-specific films,—today about war, tomorrow about love,—life throws the material at you. In the Nietzschean sense, the will to power, which is the will to life, will bring the film out eventually. This is how I made this movie, while living in Sri Lanka. You try to use cinema to express your life, but instead it’s the cinema which ends up using your life for its own purposes.

Credits: Google images

Other posts that may interest you:

- The Trouble with ‘Ecocide’

- Carbon dioxide removal – hit or miss?

- Local Victories for Turkish Opposition — A Sign of Hope?

- Are France and Japan a Mismatch Made in Heaven?

- A Reflection on Dark Tourism

Discover more from The Sundial Press

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.