By Anton Holten Nielsen

The result of the Icelandic election this Saturday is just in. More than being inconclusive, the outcome reflects the frail and uncertain political direction of a country that has only recently resurfaced from the global financial meltdown in 2008. There is little public faith in politicians following several corruption scandals and no unanimous vision for the future on either political wing. Eight parties will represent the 330,000 large population and inhabit the 63 seat parliament – yet without a given parliamentary majority. The result may be an opportunity for the ‘Left-Greens’ to break the neoliberal consensus of the centre-right parties that have dominated since the conception of the republic in 1944. In that sense, Iceland is different from its Scandinavian counterparts that follow a pendulous transfer of power from left to right. In this time of political fragmentation, a neat way to survey the landscape is by asking who was in power and who is going to be.

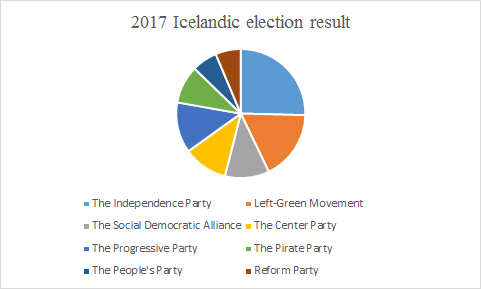

The then Prime Minister Bjarni Benediktsson, of the right-wing Independence Party (XD), called the snap-election in September after revelations that his father wrote a letter to help expunge the criminal record of a friend convicted of pedophilia. The coalition partner Bright Future left the government and prompted President Gudni Johannesson to call a new election. Notably, the election has taken place within 10 months of the last one. in 2016, the previous government fell with the resignation of The Progressive’s Gunnlaugsson who was entangled in the findings of the Panama Papers. It was therefore expected that the popular reaction to the continuous series of power abuses and scandals would lead to another, more left-leaning and anti-establishment government. However, such a clear paradigm change did not take place. Rather, the new election result is as follows, taken from state-media RÚV:

The two biggest parties are now the Independence Party and the Left-Green Movement with 16 and 11 seats respectively. Following procedure, the president of Iceland, who is elected in a separate voting process, gives the mandate to form a government — typically it has been granted to the biggest party, but the question remains whether the President deems it the best democratic practice to allow the leading government party, XD, just ousted from power, to take control of the coalition negotiations. Especially considering that the outcome opens for a left-wing coalition mirroring the leftist government, spearheading tax and social reforms, led by the Social Democratic Alliance from 2009-2013, the first of its kind in Icelandic history. However, similar to the French presidential election, the conventional labour party has gone from double to single digits in a decade. Instead, the young Left-Green Movement leader, Katrín Jakobsdóttir, is running on a platform similar to the party’s last time in government and has emerged as an almost Macron-like figure, soaring above the waters of distrust. Notably, unlike Macron’s liberalization of the labour market she seeks to liberate Iceland’s ecological resources from its incompatibility with capitalism.

Indeed, the biggest difference between the Greens and centre-right parties lie in the understanding of the financial sector and the IMF intervention that followed its collapse in October 2008. Suspiciously, though not illegally, the then MP Bjarni Benediktsson was revealed by the Guardian to have sold assets in major commercial banks hours before the official crash. It is this kind of attitude that Jakobsdóttir wants to bring an end to as she proposes to restructure nationalized banks before selling them and maintaining at least one in state hands to benefit from dividends of public investment. The Green’s economic policy as part of the 2009 government was a direct example of that with the introduction of progressive taxation, despite the concessions in relation to public-sector cutdowns, and avoiding privatization. Since then, Iceland has recovered largely due to tourism and has overall seen the economy grow by 7.2% last year and unemployment down at just 2.5%.

Still, according to economics professor Thorvaldur Gylfason: “political corruption, including the blatant failure of parliament to ratify the new post-crash constitution, has trumped economic recovery in the minds of many voters”. This dissatisfaction manifested itself in the Pirate Party becoming a political force in 2013 after several years of grassroot activism that entailed 1300 protest meetings between 2008-11. The party is distinct; proposals of a basic income guarantee to correct inequalities among students and businesses, Iceland being a safe-haven for whistleblowers, the legalization of bitcoin and crowdsourced constitution-building. The key is the free sharing of information to optimize individual potential. The party founder, Birgitta Jonsdottir, sees the party as means to end political nepotism and oligarchy by demanding governmental accountability. For the 2016 election, the party interestingly proposed a left-wing coalition of the Left-Greens, Bright Future, Resurrection and the remainings of the Social Democratic Alliance running on a platform of strengthening public welfare and redistributing profits from fisheries. To the surprise of many, the bloc received 43% of the vote, just short of a majority. Taking this as a sign of a changing political culture, the question now remains whether the left-wing coalition building will repeat itself.

Based on the election result, a coalition led by the Left-Greens would have to include the Progressive Party in addition to the weakened Social Democrats and Pirates for the slimmest possible majority of 32 seats. But as Jakobsdóttir puts it in a recent interview with Jacobin Magazine: “In Iceland we don’t have a tradition of a left-wing bloc and a right-wing bloc, as in Scandinavia, where you often know the likely coalitions. There is also a demand from the public for us to govern with the right wing, the Independence Party”. The centre-right Progressives and the newly formed Center Party will have to be consulted for a stable government to surpass the minimum majority and last longer than the previous two. The following days or weeks will hence determine a coalition that is going to oversee a significant institutional shift in Iceland regardless of the outcome. Away from the past of manipulation and disappointment and instead towards an ideological battle concerning fishing quotas, EU-accession, gender equality and sustainability.

Photo credits: Iceland Monitor / Eggert

Other posts that may interest you:

- The Trouble with ‘Ecocide’

- Carbon dioxide removal – hit or miss?

- Local Victories for Turkish Opposition — A Sign of Hope?

- Are France and Japan a Mismatch Made in Heaven?

- A Reflection on Dark Tourism

Discover more from The Sundial Press

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.