By Miko Lepistö

Image: Miko Lepistö//The Sundial Press

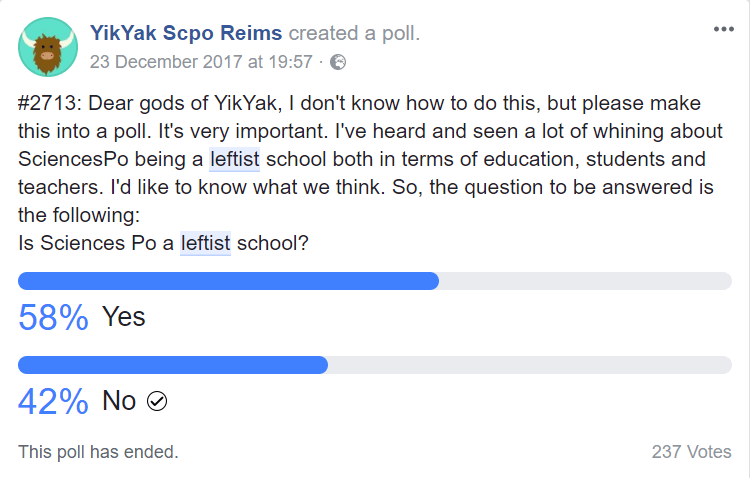

The anonymous confession page of our campus, Yik Yak ScPo Reims, has served as a platform for debates on the political nature of Sciences Po. The question “is Sciences Po a leftist school?”, yielded a 58 percent majority for those who voted yes. The poll had definitional problems, as noted by some astute commentators, but it still provides an insight into the gut feeling of the students regarding the overall political nature of their institution. It’s not fully precise and scientific, but neither is politics. I think recent political events attest to the importance of emotion and values in the res publica.

“Is Sciences-Po a leftist school?” could be divided into three further questions concerning first: the allegedly leftist nature of academic content, second: the political views of the student body, and third: the policies set and enforced by the administration. Not being an expert in all the disciplines studied, nor having access to all the political views of the students and the administration, I must resort to a more convoluted of answering the question. I will trace some of the development of the political school of thought that I believe Sciences Po subscribes to. I claim it to be liberalism, 1990s third way-ism, or Macronism.

Defining ideologies or political schools of thought is like trying to nail jelly to the wall. Any kind of definition is open for criticism, but the exercise of giving things names – or more accurately in this case, giving names things – must be engaged in to construct any kind of meaningful argument. Bear with me.

Emmanuel Macron is the pristine centrist and the quintessential liberal, and as a graduate of Sciences Po, he offers a good lens to view the issue through. He represents a convergence between the two different, but not mutually exclusive, meanings that liberal holds in European and American political discourse. In the United States of today, at least in popular discourse if not academic, liberal is very strongly associated with the Democrat party and the Left. It holds a place in opposition to conservative, which implies that the focus of American liberals is on social issues and identity politics—hence the huge importance that stances on abortion, immigration, gun control and same-sex marriage play in elections.

In European public discourse, the word liberal has a right-wing tinge to it. It is more closely associated with right-wing economic policies than anything else. Those policies are designed to protect individual (economic) freedom and as such, espouse liberal values. Emmanuel Macron has been lauded for and accused of being a liberal as well as a centrist—of being a spineless opportunist and of being a master of the art of compromise. In any case, he has earned the accolade liberal from his opponents and admirers. To caricaturize, his plan is to increase the number of female CEOs as well as the number of females in precarity. He promised that the party lists for the 2017 parliamentary elections would respect parity to further the cause of liberal feminism, while passing liberal reforms of the code de travail that will increase precarity and precarious jobs. In France, those jobs are more often held by women than men.

Macron is a liberal—economically and socially. This is not a completely unprecedented take in politics. It was already pioneered most notably by Margaret Thatcher’s greatest achievement, as she once famously quipped: Tony Blair and the new Labour party. In the 1990s the Labour party, currently being purged of Blairites by Corbynistas, accepted certain market-based paradigms as part of their political agenda, and focused on social inclusion and cultural issues as the basis of their ‘leftist’ agenda. A similar development can be observed in Sweden, where the Socialdemokraterna have driven for liberal healthcare reforms that opened the healthcare and pharmacy markets to private competition since the 1990’s, but have also pursued a radically inclusive and socially liberal agenda. A cynic might call the governments overseen by Francois Hollande to follow a similar trend due to some very liberal legislation passed under his incumbency—notably the El Khomri labour reform of 2016 and the loi Macron of 2015. Macron himself came from the ranks of Hollande’s government, and during the run-up to the election claimed to be de gauche. As the race sped up, many accused him of ditching left-wing views in favour of his liberal program—socially left, economically right.

A longer list would serve no purpose; I’m sure the idea and trend of combining economic and social liberalism to create a third-way politics has been made clear. Remember that this classification is simply a tool among others that can be used to unearth a certain pattern of political development—not a declaration of the convergence of politics and the end of history. In fact, Tony Blair stated, already back in 2006, that a new political divide has opened between open vs. closed. “Open” concerns itself more with international trade and the free movement of capital, but it is strongly correlated with socially and culturally liberal values resulting from the flows of globalization. The apologists of this theory usually loosely group hardline right wingers and left wingers together on the “closed” side due to similar economic policies, despite fault lines running through social and cultural issues.

Sciences Po is without a doubt an institution that would describe itself as open to the world, since, after all, 47 percent of its students come from abroad. Since the mid-90s Richard Déscoings and Fréderic Mion have driven Sciences Po to be a more internationally open institution—our campus of Reims is an example of this. Strengthening social inclusion by ensuring entry for students from low socioeconomic status, and establishing new specialized Masters’ schools to help integration to the job market—a process crowned by the creation of the School of Innovation and Management in 2016, could they come up with a more liberal name?—seem like policy suggestions ripped right out of a New Labour handbook.

Our academic program seeks to make us think for ourselves. It’s not mindless indoctrination by the left or the right. Sure, the economics we study is based on certain assumptions that hardline leftists refuse to accept, but we also learn to question the whole economic apparatus and its development in history classes. However, I do think that Sciences Po, along with most of its students, does like to paint itself as the open and rational liberal standing on top of the popular horseshoe model, scolding both extremes and finding a third way.

Lastly, I’d like to point to anecdote and personal experience for what they’re worth. Most students I have met have said that they voted Macron, and claim to take “a good idea, whether it comes from the left or the right.” Sciences Po follows the liberalization of politics that has taken place in the past 30 years or so, and seeks to promote liberal values during a backlash against globalization.

It is a liberal school, not a leftist one.

Miko Lepistö is a first year student from the bowels of Helsinki. The only student living on the notorious “other side of town”, as well as an avid biker due to necessity. Looney Truths runs the third Tuesday of every month.

Other posts that may interest you:

- The Trouble with ‘Ecocide’

- Carbon dioxide removal – hit or miss?

- Local Victories for Turkish Opposition — A Sign of Hope?

- Are France and Japan a Mismatch Made in Heaven?

- A Reflection on Dark Tourism

Discover more from The Sundial Press

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.