By Aurore Laborie

“Chocolate! Chocolate!”

A few kids swarmed around us on the steps of the trail. I searched my pack for some last remaining pieces of the sugary goods that my taste buds were so tired of eating after having spent six days on the mountain. Sighing as I watched my fellow travelers all handing out the chocolate they had left to the smiling children, I realized I couldn’t find where I’d safeguarded my pack of food in my backpack. I looked at it. It was muddy, filthy, and jammed with mountain gear. Most of us never wanted to eat the bars again. When you’re close to abandoning everything, when you can’t even think straight, and when you think that there’s no way you’re going to make it, the chocolate bars were edible. Now, so close to the finish line, I couldn’t look at the purple wrapper without feeling a bit sick. I’d eaten enough chocolate for a lifetime.

In October 2017, my family sat around the table, eating and discussing what we should do during Christmas break. Last year, while still living in the United States, we had traveled to Patagonia, in Chile, and hiked the W trek. During the summer, my dad and I had climbed Grand Teton, which had been a truly extraordinary experience for me. We wanted more. My sister proposed that we climb Mount Kilimanjaro in Tanzania, Africa’s highest summit. At the time, it was just that, a proposition. A month later, my parents announced that we were going. I was excited. It was our first 5000 meter climb as the Kili is 5895 meters high, which is spectacular for a mountain since it is not part of a mountain range like Mount Denali, America’s highest mountain. No, the Kili is exceptional. It rises, so high, out of nowhere, next to its counterpart, Mount Meru, which rises to about 4000 meters. Agreeing to do this was a bit crazy. We’d only started to think about it, and only three weeks later, we found ourselves at the foot of the mountain. Gerard, a wonderful 68 years old man who had decided to challenge himself had been training for months. On the other hand, I’d been injured three times on the same ankle in four months, and was just recovering.

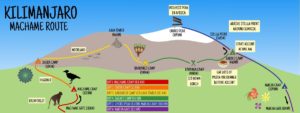

Mount Kilimanjaro is located in Tanzania, although there is a climbing route that starts in Kenya. Our guides were still adamant in saying that Tanzania was the only place to climb the summit. There are about seven different routes to get to the summit, and we chose the Machame route, which is six days long, and soon to be extended to seven days so that hikers better adjust to the high altitude and get less tired before summit day. The Machame route is also known as the “whiskey” route because it is harder than most routes, known as “coca cola” routes.

The Climb. From 1600m to 5895m.

“Our route” Photo: Aurore Laborie// The Sundial Press

Rain. So much rain. Each and every day. Looking at pictures a week later, I realize that we saw the sun only on the second day, for ten minutes (enough time to take pictures of the mountain), and on the fifth day (summit day) when we were on top. As a result, the sun graced us with its presence during the two most important times. This was great since spending six days in mist, rain, and snow is not fun. The first few days I’d still bother to take off my rain gear and pack it up, hoping that the next day I wouldn’t have to use it. By the time we got to the third day, I stopped. It’s ironic to think that when we were packing, the company told us that we could bring an umbrella, and I actually laughed, saying “who in their right mind would take an umbrella to 5895 meters? It’s a hike, not a shopping trip!”. Karma slapped me in the face. Most porters had one, and Gerard had brought one to. He was probably the least wet out of all of us. You have to master the art of hiking over huge and slippery rocks while holding an umbrella, but once you do, it’s so much better!

“Starting under the rain Photo: Aurore Laborie// The Sundial Press

The Kilimanjaro mountain is very interesting because the scenery changes from one day to the next. In fact, there are five different types of terrain going from tropical forest, where we saw blue monkeys again, to rock desert, to the white snowy paradise of the summit with its many glaciers. Minus the mist and rain, we were still able to see how the mountain shifts the more we climbed.

Porters. I have to mention them. For a group of 15, we had about 30 porters. Out of all of us they are the bravest. Porters carry 20 kilos on their backs and have to walk faster than us so that our camp is fully set up once we arrive at the end of the day. They faced the same horrible conditions that we did, except with many more smiles. Our guides screaming “JOHNNY! maji ya moto!!”, meaning hot water because we asked for tea, will forever be ingrained in my mind, as well as “hakuna matata!”, which to foreigners reminds us of the Lion King, but they actually use the saying all the time.

“Our team of porters” Photo: Aurore Laborie// The Sundial Press

The first two days, we hiked for about four to five hours. On the third day, the goal was to hike all the way to 4600 meters, and then go back down to 3900 meters for the night. We hiked seven hours, and it was our first touch with high altitude. I caught a splitting headache and felt drowsy all the way to camp. The next day, we climbed to 4700 meters. It was not pleasant. Rain kept pouring down; the trail was slippery and dangerous; and we couldn’t see anything. I had not slept much due to the high altitude, so I started to feel the effects caused by lack of sleep. Nonetheless, like Erasto kept repeating “On s’arrache” and “On est pas d’ici”, so we kept moving.

“Day 3 arrival to camp, amazing weather as always” Photo: Aurore Laborie// The Sundial Press

The fifth day was the day we climbed all the way to the top. We woke up at 11:00 p.m., and started the climb at around midnight with our headlamps on. It was cold, and dark. We couldn’t see much besides hundreds of small lights glistening and moving slowly up the mountain. I started with a stomach ache. Others felt the need to vomit, and one actually did. Can you imagine walking 10 hours with nothing in your system but cereal bars? Another had gastric issues and had to stop literally every 10 minutes to go “to the bathroom”. She was the bravest out of all us if you ask me. It destroys your strength and makes you weak, with no energy left, and yet here she was, next to me all the way up. The climb up was hell. Not because of the weather as it wasn’t so bad, despite the cold, but because it was unbearably long and tiring. Each time you felt as if Stella Point was near, you ended up climbing another hour, and another one, and another one. I struggled more than anyone due to tiredness. I suffered the last six hours of a eight hour long summit climb. I couldn’t think. I had no energy left. My mom had to feed me because I didn’t have the strength to do it myself. My legs were logs. I tripped, staggered, stumbled. My batons dragged behind me, and I swayed due to dizziness caused by the high altitude. It’s an unbelievable experience to feel so close to your breaking point, to know that the next step might be your last and that you might collapse and faint right there. The day before, I’d seen some Americans coming down the mountain. They were in a bad state… One of the ladies could barely write her name in the log book. They had to be carried around by the porters and guides and couldn’t do anything. Thinking back to them as I put another foot forward and felt my leg tremble from its weakness, I began to realize that I might end up like them. I used to relish the physical pain of pushing your limits in sports, but the pain of climbing Mount Kilimanjaro is one I’d never felt before. You are physically and emotionally numb. When you arrive at the top, everyone is in a state of semi-consciousness, drained. This can be extremely dangerous because it can lead someone to make a wrong move such as forgetting to put a glove back on and thus lose a finger to the bitter cold (-28 celcius). I remember one of the guys with us trying to tell one of the girls, whose hands were cold, to make large fast circle movements with her arms. She could barely hold them out. On a mountain, at such a high altitude, anything can make your day a complete disaster. The wrong pair of socks can stop you from making it to the top.

When you get to Stella Point, the top of the crater, you hike for about an hour on the edge to get to 5895 meters, which is Uhuru Peak, the highest point of this ancient volcano. My father had to hold my arm throughout the way because I kept collapsing. Arriving at Uhuru Peak, I remember panicking because I didn’t think I had the strength to go back down. Hikers only stay ten minutes up there due to the really cold weather but these minutes will be the most precious ones of the journey.

“Stella Point” Photo: Aurore Laborie// The Sundial Press

At 5895 meters, relief was the only thing I felt. Some of us did shed a few tears. I forced myself not to, though the emotion of having made it did overwhelm me. The worst was over. The scenery was stunning. Glaciers surrounded us as we struggled through the wind, and everything glistened, white with snow. The crater was huge and everything looked so peaceful, untouched by human hands. The sun welcomed us as we arrived, and stayed with us the time it took to take pictures, and then left, as if it had done its part in making this journey worth it. We were so high, we sat above the clouds and could barely glimpse the world beneath us. We felt small. This reminded me that we should remain humble when facing the Earth. She has granted us stay on her beautiful soil, we best remember that we are only guests for if we cannot appreciate her kindness, then she will send us to leave. After seeing some of nature’s secrets, I hope to remind everyone that we keep this planet safe and pure.

“Glaciers from afar” Photo: Aurore Laborie// The Sundial Press

There are no words to explain the feeling of being so high and so far away from everything. It’s why it is so difficult for me to tell people how it was when they ask me. I always think, “well, it was the most painful thing I’d ever done, I cursed my whole family for having brought me up here, and yet I’d do it again and again if I was asked to come back.” Nonetheless, despite all of that, I made it to the top, and down. I am “a proud ambassador of the Kilimanjaro” as our guides would say. It took me a whole week to recover from the lack of sleep and regain the strength in my legs.

“My family at Uhuru Peak, 5895 m, top of the Kili” Photo: Aurore Laborie// The Sundial Press

“Snapchat never failed me despite a -28 degrees celcius temperature” Photo: Aurore Laborie// The Sundial Press

To show in numbers how hard the climb actually is: only 45% of climbers make it to the summit. Our 15 person group was an exception as only two people did not manage to summit. So what makes me special? How come I made it when 55% don’t? No matter how many times I told myself, “stop you can’t do this”, I kept putting one foot in front of the other. As long as my feet managed to hold me up despite the wobbling, I kept pushing. Some might call it stubbornness. There was no way I was stopping no matter how much I wanted to. It’s almost stupid. Why climb a mountain only to come back down? Why do I care? I didn’t have anything to prove to anyone but me. However, I care about what I think of myself. Climbing to the top is just another way to prove to yourself that you are strong, independent, and can do literally anything. The exhilaration that comes after this is incomparable to anything most people will ever feel in their lives. I feel high just thinking about it.

“Me getting my diploma from my guides that certifies that I climbed all the way to the top” Photo: Aurore Laborie// The Sundial Press

My trip to Tanzania was a beautiful human experience. The fourteen companions who spent seven days with me were the most wonderful people I had met in a while. Not a day passed that we didn’t laugh, and despite the horrible conditions each woke up with a smile on their face, ready to joke through another rainy day. Our group is what got me all the way to the top, and I thank each one of them for having motivated me, and made this journey as epic as it could be.

It’s amazing how hiking really enables one to discover a country. I have hiked many a mountain, on multiple continents in fact, and I find that trekking is one of the best ways to uncover the beauties and wonders of Earth because there is nothing more ravishing to the eyes than staring down at the world from 5895 meters above.

“The Kili, day 2: imposing and magnificent” Photo: Aurore Laborie// The Sundial Press

Other posts that may interest you:

- The Trouble with ‘Ecocide’

- Carbon dioxide removal – hit or miss?

- Local Victories for Turkish Opposition — A Sign of Hope?

- Are France and Japan a Mismatch Made in Heaven?

- A Reflection on Dark Tourism

Discover more from The Sundial Press

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.