Image courtesy of Omran Aldoumani, volunteer photographer in Ghouta

As human rights advocates and professional journalists reiterate, for the thousandth time, same words which ring hollow, the least we can do is never forget.

Omran Aldoumani usually spends his days either wandering the small streets of Douma to document daily life in the besieged town, or sitting in his small office by a window completely destroyed by a shell having landed nearby. Now that the Assad forces have escalated aerial attacks on the opposition-controlled areas in the Damascus suburbs of Eastern Ghouta, which Douma is part of, he has also started shooting pictures of Syrian and Russian aircraft engaged in heavy bombing of the region from his rooftop.

Rescuer carrying a child away from the site of an airstrike in Ghouta

“The fate of my family is the fate of al-Ghouta,” says the 18 year old volunteer photographer for the Ghouta Media Center. He cannot know what will happen, but doesn’t want to leave even if Assad forces reconquer the opposition-controlled suburbs East of the Syrian capital. “We’ll see”: these words sound almost too casual for someone who is surviving a massacre which some compare to Srebrenica.

But comparisons don’t necessarily do Ghouta justice. Each atrocity may stand on its own terms.

This is what “hell on earth” looks like

The never-ending siege of Eastern Ghouta, started in April 2013, has deprived thousands of urgent medical care and supplies in food, which occasionally enter the besieged area with the help of several businessmen having ties to both the Syrian government and rebels, thus acting as power brokers, or through bribes to the regime officials controlling the checkpoints.

Ghouta has also been the site of the first major chemical attack of the Syrian war, involving the nerve agent sarin which killed hundreds. Since then the region has faced an unprecedented bombing campaign, from ground-to-ground missiles alternating with airstrikes, to the repeated use of chlorine rockets and barrel bombs.

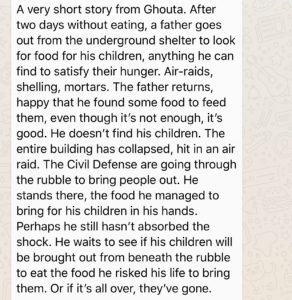

A story posted by journalist Julia Macfarlane

Last Friday, after several world leaders’ call for ceasefire, the regime briefly paused the operation to drop leaflets indicating a potential way out for the citizens of Douma (needing to pass through a military checkpoint near the al-Wafideen refugee camp to escape). Omran stayed faithful to his promise not to leave his childhood home, a great part of which have been destroyed, and he claims that the majority of Ghouta did the same. In any case, less than 24 hours later, Assad resumed the attacks, now using white phosphorus-filled munitions against residential areas.

The “humanitarian corridor” which Assad claimed to provide distracted from what constitutes an effective attempt at a forced displacement of civilians (defined as a war crime by the Fourth Geneva Convention), as well as indiscriminate attacks on residential neighbourhoods, rescue workers and civilian infrastructure.

Douma, center of Rif Dimashq governorate, has been the site of several massacres committed by the government forces

In addition, out of the 500 “severely ill or wounded civilians” that the UN attempted to evacuate in the previous months, only 35 were allowed to leave by the Syrian government, and this, only following a release of several detainees by the fighting factions. In the past, Jaysh al-Islam, one of the rebel groups, has allegedly prevented civilians from fleeing Eastern Ghouta. Meanwhile, many others are concerned with the possibility of persecution by the Assad regime, arbitrary arrests and the compulsory military draft.

Therefore, while the war crimes perpetrated by the warring factions in Ghouta,—such as the alleged shelling of residential Damascus districts by rebel mortars in response to Assad’s bombardment,—should not be brushed under the carpet, any claim of equivalence is misguided and only disregards the plight of Ghouta civilians.

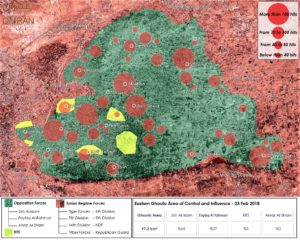

The government’s military strategy in Ghouta

In addition to the classical airstrikes, Ghouta’s first respondents have recently accused the government of using chlorine weapons, as recently as Sunday. As the opposition-controlled Syria has been shrinking since the fall of Aleppo in 2016, Assad has been frequently described as “winning” the war, which, according to some, would make the usage of chemical weapons all the more puzzling. But Ole Solvang, who has previously documented aerial attacks in Syria since August 2012 as part of the Human Rights Watch emergencies division and who currently works at the Norwegian Refugee Council, argues that the strategy behind such weapons may be “creating fear” as well as “making places that were otherwise safe unsafe”. Currently, shelters dug underground are the Ghouta civilians’ primary means of protecting themselves from air strikes. Solvang reminds that “chlorine is heavier than air and would seep into [these] shelters. This makes it even more difficult for civilians to protect themselves, because there are no places left to hide.”

Yet, he clarifies that a lack of coherent national strategy is possible, as “chlorine weapons are not home-made, but not industry-produced either. These aren’t the kinds of weapons that require the authorisation of President Assad [or other senior government figures]. Of course, this does not relieve the latter of responsibility, given that it is a chain of command and they are responsible for what weapons their troops are using.” The decision to attack Ghouta with chemical rockets and barrels may in theory be taken by regional military commanders, especially “in areas where frontlines have been static for a very long time. For example, in Aleppo, the government was systematically dropping chlorine bombs close to the frontlines and as [those shifted, so did the chlorine attacks] falling just ahead of them to drive people away.”

This highlights the seriousness of the attempt to retake Ghouta, at a moment when the government is redeploying various forces on the ground. For instance, the so-called “Tiger Forces”, previously used for cutting rebel supply lines during the battle of Aleppo, have been moved near Ghouta’s frontlines. Bellingcat’s Cody Roche, who has been documenting the evolving factions fighting in Syria, doubts the “Tiger forces will do any better in Eastern Ghouta. It’s a difficult urban environment, all they can do is throw men at it and that requires many casualties just to take one block. It doesn’t matter if the regime uses conscripts or so-called elite forces, that isn’t the issue. Eastern Ghouta factions are more united ([there are only] 2 main groups) and they are indigenous to the area.”

On the other hand, Russian Air Force assistance to the Assad government might be the decisive factor in determining the battle’s outcome. Describing the battle of Aleppo for The Century Foundation, the Levant Front’s Jumu’ah Abu Ahmed claimed that “Russian air support changed the equation on the ground.” Supported only “with regular ammunition, and with money,” the opposition was unable to compare to “Russian and Iranian support, it wasn’t enough—it was a holocaust.” These words sound all the more ominous as Russia has increasingly taken an active role in the Ghouta campaign, after deploying two new advanced jets to its Syrian airbase last week.

A Syrian military helicopter dropping a barrel bomb on Ghouta

Ole Solvang believes that sooner or later, “we may see one of these ceasefire agreements, that we’ve seen in many other places [including Aleppo], when eventually the remaining fighters decide to give up and get evacuated to Idlib alongside many civilians. I think the bigger question is what the Syrian and the Russian government will do to Idlib, because from there, people now have nowhere else to go.”

The failed ceasefire

As the number of civilian deaths in Eastern Ghouta escalated beyond 500, two hours late, the UN Security Council proceeded to vote on a 30-day ceasefire resolution following a number of delays. Undermined from the start, the resolution did not take into account the attacks directed against ISIS, al-Qaeda and “associated groups”—a way out for the Russian joint campaign with the Syrian government. Even though Ghouta has a very limited presence of fighters associated with Hayat Tahrir al-Sham (or HTS, see map below), whose predecessor Jabhet al-Nusra had previously been considered “al-Qaeda’s branch in Syria”, Russian Foreign Minister Lavrov indeed claimed that they were the principal problem.

A map from the Omran Studies think-tank (from February 23, 2018) showing that most government airstrikes target heavily-populated areas with no presence of jihadist forces

Regardless, the ceasefire was not simply broken, but rather completely disregarded, as on the next day of the vote the above-mentioned Tiger Forces announced that they did not “give a toss about what the UNSC decides” and that “Ghouta [would] be recaptured”. Then, in just a few hours, Ghouta was subjected to more than 70 airstrikes and dozens of barrel bombs and new reports of chlorine use resurfaced. The reports that Vladimir Putin is ordering 5-hour daily ceasefires, in addition to making a mockery of UN Security Council’s demands, are also hard to take seriously.

It is impossible to imagine the brutality of the siege of Eastern Ghouta without having lived there. The deadly operation to recapture Eastern Aleppo in 2016 regularly made headlines, but even that may pale in comparison to the operation the government has now dubbed “Damascus Steel”.

Global activists and civil society organisations have promptly suggested numerous ways to help, from emergency fundraisers to feed Ghouta families to global demonstrations and calls for a no-fly zone. But the Russian-Syrian killing machine that has turned its eyes on the Damascus suburbs has so far been unavertable.

That’s why, tuning into the news from Ghouta every morning, I check Omran’s latest posts, always fearing a tragic update. “If you see a green light next to my name on Messenger, you’ll know I’m safe”. Thus far, he has been, according to his own words, “survivor until further notice”.

Ghouta (photo by Omran)

Other posts that may interest you:

- The Trouble with ‘Ecocide’

- Carbon dioxide removal – hit or miss?

- Local Victories for Turkish Opposition — A Sign of Hope?

- Are France and Japan a Mismatch Made in Heaven?

- A Reflection on Dark Tourism

Discover more from The Sundial Press

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.