By Adam Havelka

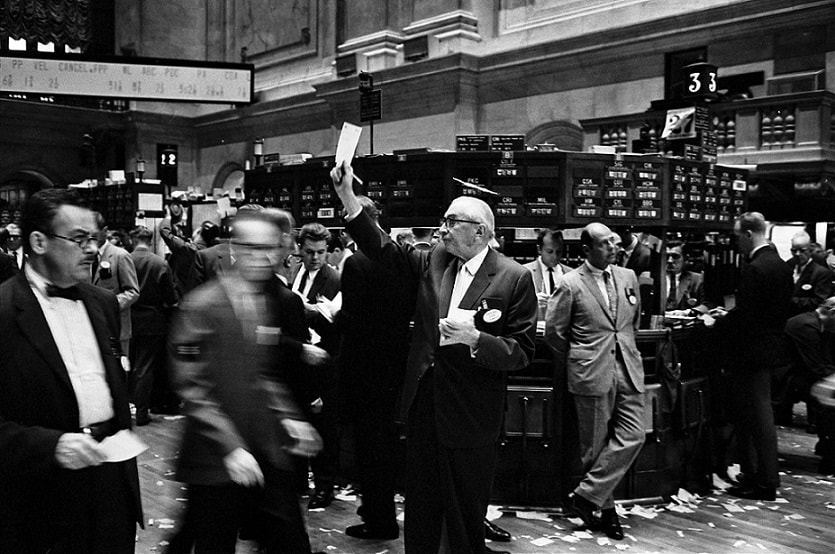

Cover Photo: Stockbrokers at the New York stock exchange, 1963. Photo: Thomas J. O’Halloran

In the movie Melancholia by Lars von Trier, one of the main characters looks through a wire ring at a rogue planet distraught with the possibility that it may be heading for earth. She waits a couple of minutes and repeats the measurement with her wire ring device. It then looms on her. The planet has outgrown the ring. It is headed for Earth, destroying everything in its path. The only question left to answer is when it will hit.

Similar analogies are often invoked when economists talk about the next financial crisis. The only things that seem to be certain in life are death and an eventual economic meltdown. You might think that perhaps the hysteria surrounding an economic crisis is overblown. It is, after all, only a crisis of money. The reality, however, is that it is much more than that. According to a metanalysis conducted in 2011, a person who loses a job experiences a 63% hike in all-cause mortality. We cannot disregard other important and well-documented factors, such as increases in poverty rates and inequality as well as decreases in the quality of education and healthcare in times of crises.

Economists like to say that the economy moves in cycles. There is a period of growth followed by a so-called market reset or a period of economic downturn, and then the whole thing repeats itself. Leading up to the 2008 crisis, the general opinion was that through planning and robust financial frameworks we would be able to mitigate the impacts of such crises, eventually rendering them unable to cause widespread harm. But the housing bubble and the unregulated financial market had other ideas. What became painfully clear was the inability for economists to successfully predict not only the crisis itself but its causes and ensuing impact. When the world’s leading financial experts and economists came up with a plan to counter, they employed aggressive tactics to expand money supplies. Governments in most countries followed suit with similar expansionary strategies, and, eventually, these stimuli collectively became known as the “period of quantitative easing 2.0”.

The important thing to understand is that quantitative easing was not a standard measure and only became a necessity when the initial impact of the crisis coupled with a low-interest rate at which the central bank’s lending processes were already operating. Fast forward to present day and the benchmark interest rates are still very low, which in turn gives little to no wiggle room for central banks to work with should the need arise. Central banks all over the globe have, ever since they were first introduced, been very wary of both ending quantitative easing prematurely and raising benchmark interest rates amid concerns of backlash and increased volatility. Coupled with the occasional jab at the US Federal Reserve by Mr. Trump and his breed of right wing populists and you are left with institutions that are supposed to be at the frontline of all future troubles unable to fully deploy the protective shield they are supposed to wield in the face of a potential crisis.

Ask a random person on the street what caused the 2008 crisis and you will get an answer varying from greed to mortgage-backed securities. Put more simply, extraordinary events, exotic products, or bad apples. Over time, however, it has become clear that meltdowns are an inherent part of capitalist economies. Whatever the cause or causes for the next financial crisis may be, it will not be caused by an idiosyncratic market failure, nor will it be caused by a systemic slowdown of the markets. It will be a combination of insufficient regulation, overaggressive risk-taking, and structural flaws of the economic system that has brought us a stark increase in wealth ever since its inception.

It would be naïve to think that crises are caused uniquely by the financial system of any given economy. Yes, banks and financial institutions certainly do exasperate some of the problems stemming from a crisis but are not the causes in themselves. In 2008 it was the mortgage market that had initially enabled the dangerous and malign mix of deception and greed to flourish. The toxic mortgages that had been made in the process were then scooped up by the financial institutions in large quantities. These mortgages then got tangled together in derivatives, or financial products incorporating bundles of different kinds of mortgages. The companies whose job was to rate the quality of these bundles of mortgages knowingly distorted the risk carried in these derivatives amid the fear of losing customers to rivals willing to do just that. This crooked system met its demise when a large percentage of those mortgages defaulted, triggering the defaults of the derivatives built around them. What happened next triggered a global crisis only comparable to the Great Depression.

What is sometimes lost on most people is the extent to which the last crisis was an international disaster more than an isolated incident in the United States. The seemingly distant problems triggered a domino effect that resulted in major downturns in all global markets. The Eurozone found itself in turmoil that has shaken the idea of a feasible common currency to its core. Not only were European banks like Deutsche Bank or Credit Suisse directly involved in the schemes that gave rise to the crisis in the first place, but European institutions did a poor job of securing the market amid irresponsible policies of member states. Crises have thus become instant, global, and increasingly hard-hitting.

Through meaningful regulation, better education, and, most importantly, close scrutiny of decisions made by those in executive positions, we can move towards a system that is more resilient and less prone to having exploitable backdoors similar to those exploited in 2008.

In the current environment of market volatility and increased tensions, some have begun to sound the alarm already. If this turns out to be the case and the crisis hits somewhere in the horizon of the next two years, it is fair to say we are ill prepared. Better bring out your ring wire and start measuring, like the main character Melancholia, who helplessly watches the impending collision between earth and a rogue planet.

The wire ring from the movie Melancholia. Photo: screenmusings.org

Adam is a Slovak first-year student in the Euro-American program at the Reims campus of SciencesPo. Apart from binge-reading the Washington Post in order to satisfy his constant urge to be up-to-date, he enjoys economics, finance, and political philosophy. While being an avid fan of sports he also loves cinema and existential dramas.

Other posts that may interest you:

- The Czecho-Slovak Century and what it means for Europe today

- Trump, the United Nations and Alt-International Relations

Discover more from The Sundial Press

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.