Emilie Rappeneau

“The misery of being exploited by capitalists is nothing compared to the misery of not being exploited at all.” – Joan Robinson

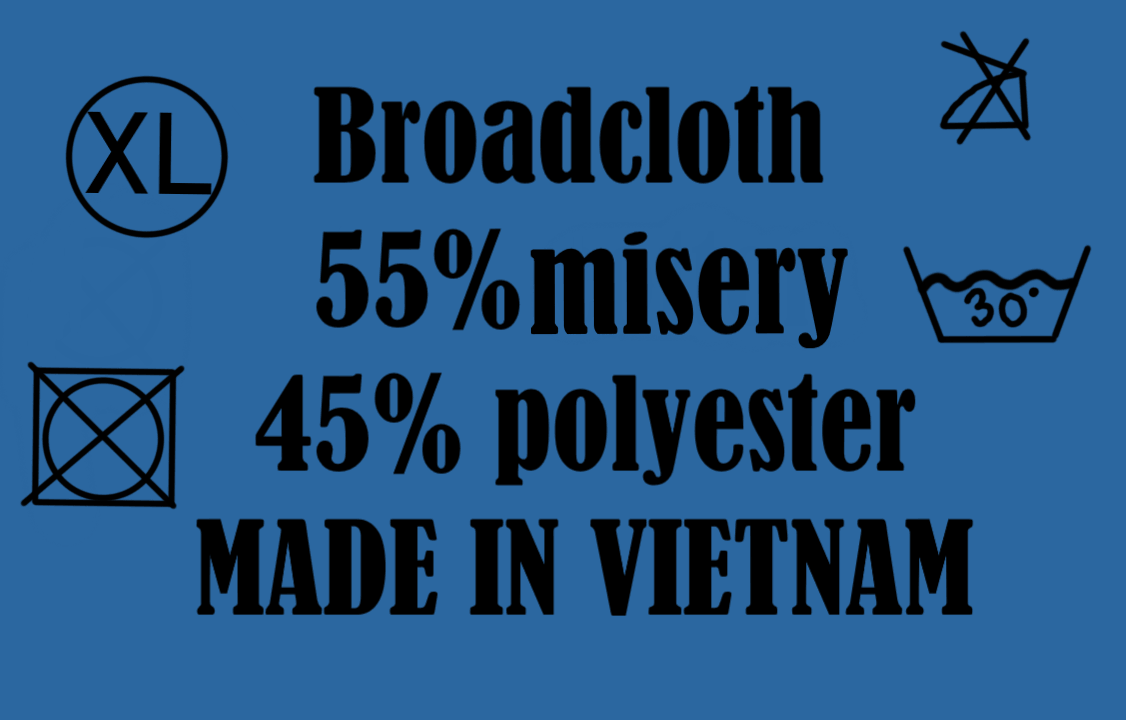

Articles and studies dedicated to redeeming sweatshops have flourished in the West. The average first-world citizen is either exposed to sophisticated research that describes sweatshops as escalators out of poverty, or to media-enhanced moral outrage at the squalid working conditions behind the production of our apparel. On the one hand economists like Jeffrey Sachs bluntly state that “my concern is not that there are too many sweatshops but that there are too few” and on the other, documentaries like The True Cost make accusations that deeply disturb our consumer morality.

Blinded by cheap prices and backed up by the Paul Krugmans of the world, we soothe ourselves by believing that our high consumption of cheap goods actually helps other countries reach the capitalist haven of industrialization. Historically, these theories go back to Sir Arthur Lewis – a key figure of development economics and a Nobel Laureate – who believes sweatshops to be a lesser evil than rural poverty and the extreme precarity it represents. According to him, the urban manufacturing sector helps move low-skill workers out of the countryside and into the cities, allowing the country as a whole to boom. It offers stable wages, unlike other sectors, and lifts the disadvantaged out of poverty. How convenient!

A Sundial Press article from last year judged the pros and cons of sweatshops, and came up with one very forceful argument against traditional development theories. Namely, a study conducted by Christopher Blattman and Stefan Dercon which shows that in Ethiopia, working in a sweatshop is not the golden job opportunity that Sachs, Krugman, and Lewis make it out to be. The manufacturing industry has a huge turnover rate because the work is dangerous, and other sectors, like agriculture or entrepreneurship, actually offer similar wages. So much for the “better than nothing” argument.

Despite this welcome criticism by Blattman and Dercon, the solutions they proposed were disappointing: better human resource management and improved social welfare systems. Nothing revolutionary, merely the attempt to make murderous factories a little less dangerous so that desperate workers do not have to risk their lives in order to bring food to the table. But even the reforms they demand are suggested to be enacted on an “appropriate scale”. God forbid workers be paid too much, too quickly, or that factories be equipped with more than one fire exit for thousands of workers.

Half-hearted criticism, such as that found in the study on Ethiopia, and over-the-top nuance, as seen in the earlier Sundial press article, sinks us into mediocrity. We deny the gritty reality of sweatshops by insisting on their importance for modernization, or we offer uninspired and moderate solutions because we claim “it’s complicated”. Solutions require a strong moral stance, belief in change, and political will. Know that nine-dollar shirts are not the natural result of the miracle of capitalism, but rather “the result of discrete policy decisions undertaken in recent decades by the U.S. government and the W.T.O. [that] not only to permit but favor outsourcing to countries that lack environmental protections and basic labor protections.” You already know, without the shadow of a doubt, that merely hiring better sweatshop-managers is not enough. We need something bigger.

Low wages and killer factories are competitive and bring in foreign capital, for sure, but what about a worldwide rise in wages, employee protection and working conditions? Would that not bootstrap industrialization by increasing purchasing power, and replacing dehumanizing jobs with more empowering ones? It is vital that we stop our systematic opposition to decent working conditions and industrialization if we want, one day, to be able to indulge and buy cute jacket without any afterthoughts. Firms would of course need to raise prices in order to maintain their profits, but I firmly believe a small change in purchasing practices – buying one slightly pricier item instead of several cheap ones – is worth the trouble.

However, the devil is, as ever, in the details. How can we bring about this hypothetical boost? Extrapolating from the historical European experience, labour unions could be the solution. They would fight for rights in the garment industry, even though some say this would only create a labour aristocracy, a factory elite, leaving other underpaid sectors behind. On the contrary, I believe a bottom-up union movement, starting with sweatshops but espousing solidarity, would very likely spread into other sectors. However, seeing as sweatshop workers are easily replaceable, and the existence of the industry relies on docile low-cost labour, potential union movements tend to be suffocated. For example, in Bangladesh, the government has made union registration as burdensome as possible, and union activists regularly face threats of dismissal and violence.

Is it not up to us, those fortunate enough to live in states providing adequate workers’ rights and civil freedoms, to denounce this blatant disregard for basic human needs? Installing procedures to investigate unfair union-busting by labour authorities should be a priority, if we want to one day live in a world where everybody is paid decently for a safe and humanizing job. Capital and its defenders are global, could the camp for workers’ rights one day be rebuilt in the same form? Could unions and their defenders go global?

I by no means pretend to have the answer. In the end, there is a lot to be said about the positive effects of globalization and modernization. But if hundreds die each year, if we know that local workers are not content and their attempts at unionization are crushed, if we know that our obsession with cheap fashion is unsustainable and immoral, should we not seek something else? Do not be swayed by the false prophets who seek to beguile you into rationalizing exploitation. Children working hundreds of hours for a meager salary is not right, no matter the alleged worldwide benefits of industrialization.

Ps. Before you go off to win the next Nobel prize in development economics, please sign this petition to end sweatshops.

Emilie Rappeneau is a French first-year Euram student from Poissy who writes for the Opinion section of The Sundial Press. She talks too much, sleeps too little and loves to write silly poems. When she’s not procrastinating, she can be found defending veganism, binge-watching Friends or playing the ukulele.

Are you angry? Do you disagree? Write a response column by first contacting the editor, and we’ll publish your dissenting opinion.

Other posts that may interest you:

- Quand la sécurité prend le pas sur la liberté : les défauts du règlement Dublin

- The Pros and Cons of Effective Altruism

- When the Economy Screams, We Bleed

- Rote learning is Not Learning At All

Discover more from The Sundial Press

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.