After seven months in France, I have lost track of how many times people ask where I come from. “Canada,” I usually reply, “the land of four-month-long winters, maple syrup, a rarely mentioned history of genocide…. and free healthcare.”

Photo by @timhortons, Instagram.

Images of Tim Hortons logos, the snow-capped Rocky Mountains, and a grinning Justin Trudeau marching in the Montreal Pride Parade play into Canada’s image as “America’s friendlier neighbour.” According to The Reputation Institute, Canada has consistently ranked among the most reputable countries in the world based on criteria such as technological advancement, natural beauty, government effectiveness, and ethics. The “true North, strong and free” alternated between first and second place in this study from 2012 to 2017, before dropping to seventh place in 2018.

But Canada’s sparkling facade has been carefully buffed and polished to mask the more brutal parts of its history, particularly the widespread mistreatment of the Indigenous population that is older than the Constitution. North America was built on the oppression and genocide of Indigenous tribes – and Canada is no exception.

Although today the country prides itself on multiculturalism, it has a legacy with darker, colonial undertones. The arrival of Europeans in the fifteenth century began a process of domination in which the colonizing minority eventually became the majority by decimating the hundreds of Indigenous tribes that inhabited ‘Turtle Island’ (the North American continent) for twelve thousand years. The Indigenous peoples had little to no say in the shifting balance of power, left out of a developing European-dominated system that became increasingly hegemonic.

In 1876, the Canadian government passed the, still in force, Indian Act – a federal initiative that granted the government control over various aspects of Native life, including limiting the practice of Indigenous traditions and languages. Government control manifested in the residential school system, state-run schools that collaborated with churches to assimilate and “civilize” Indigenous children.

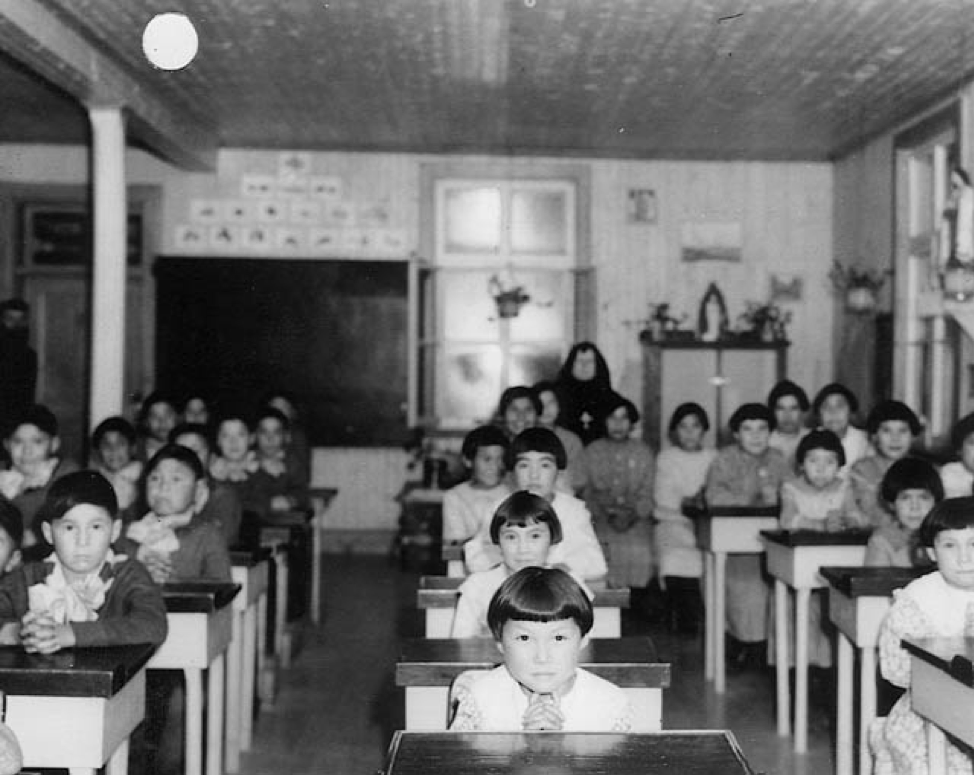

Indigenous children in class at the Roman Catholic Indian Residential School, Quebec. Photo: Where Are The Children @wherearethechildren.ca/en/

In residential schools, children were taken forcibly from their parents, given new names, and raised in school dormitories by administrators who were appointed full guardianship. The institutions were cheaply constructed and under-supplied; thousands of children died from tuberculosis outbreaks and the poor living conditions. Counts of physical and sexual abuse, sometimes resulting in torture and death, were ignored by the state.

In 2008, Prime Minister Stephen Harper issued an official apology and began the Truth and Reconciliation Commission to investigate what was eventually deemed a “cultural, physical and biological genocide.” It was the first step on a long road of superficial gestures and inadequate actions that fail to address the critical issues concerning Indigenous peoples.

More than ten years later, little has changed when it comes to Indigenous rights. Native reservations continue to be plagued by inadequate educational institutions, as well as poverty , alcoholism, drug abuse, mental illness and suicide at rates which are much higher than the national averages – all of which can be linked to a cycle of abuse and intergenerational trauma.

Photo of the Attawapiskat Reserve in Manitoba. Photo: Charlie Angus, Ottawa Citizen

Elements of exploitation and an imbalanced power dynamic still colour the relationship between the Canadian government and First Nations tribes today. Despite repeated promises to prioritize Indigenous issues, the government has done little more than slap a Band-Aid over an open wound.

This is not to say that Prime Minister Justin Trudeau has not been taking action. In September 2016, he launched a national inquiry into missing and murdered Indigenous women and in February 2018, the Prime Minister outlined a plan to reform the legal framework of Indigenous rights (the details of which he was careful not to specify).

But in the true spirit of Canadian politics, governmental bodies treat Indigenous issues in a way that tries to disguise the Band-Aid as a life-saving tourniquet. Declarations like Trudeau’s have been made before, but real change has yet to be seen. His pledges are especially difficult to believe when they are undercut by contradicting government actions – like the nationalization of a Trans Mountain pipeline Expansion Project that cuts through Indigenous land, or the decision announced by premier, Doug Ford, to end efforts to emphasize Indigenous history from the Ontario education curriculum. The Government of Canada seems to think that the threat of the Trans Mountain pipeline infringing and polluting Squamish territory can be excused by renaming National Aboriginal Day to National Indigenous Peoples Day.

Canadians are fond of apologizing, but “I’m sorry”s do little to erase centuries of oppression and reverse the making of Indigenous peoples into third-class citizens on their own land. When it comes to addressing the deep institutional fractures in Indigenous communities, the Canadian government swings but ultimately misses. Canada needs to not only take responsibility for the continued mistreatment of its Native population but also to start fixing it.

Other posts that may interest you:

- Be Radical, Not Neutral

- Sexual Violence in the Spotlight

- 100 Years at Vimy Ridge

- Listen to my Politically Correct Opinion

- Why I Don’t Bother Coming Out

Discover more from The Sundial Press

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.