My grandfather spent four of his teenage years in the outskirts of Siberia, surviving on 300 grams of bread per day, working as forced labour to bury those who had frozen to death. All at the age of 12. Thank you, comrade Stalin, for [his] wonderful childhood.

We have all learned about the atrocities of the Soviet regime and in some classes we even compared it to the Nazi one, questioning who ranks higher on the evil scale, reducing the ruthless bloodshed to a debate of quality versus quantity. Despite the non-malicious intent of such discussions (or wearing of a t-shirt), we tend to trivialize the sheer extent of human destruction the regime caused. When talking about USSR, we somehow end up with the paradox of a forgettably high number of deaths with no discriminatory idea to link them. The mass killings and famines were seemingly indiscriminate, sparking no dramatic interest for the popular memory to form a narrative. On the other hand, the British, Japanese, and German empires created a rhetoric based on biological inequality, giving the international community something specific to rally against. However, when you are being shot down or starved to death, how much does the official discourse of your killer really matter?

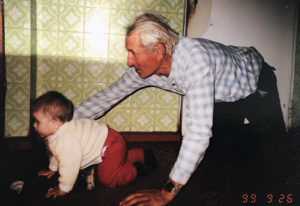

My grandfather and his brother in a Lithuanian forest (c. 1959). Both of them mandatorily served in the USSR army. Photo: Ieva Salnaite

The Soviet Union, despite its ideological claim of camaraderie, had at its core the same imperial repertoire of repression, eradication of culture, social engineering, and violence. Thanks to the popular depiction of them as the “representatives of communist ideals”, however, their horrendous deeds have at times been disregarded in light of the positives. People are quick to point to the Soviet Union’s gender equality, defeat of the Germans or anti-colonialist endeavours.

These are the arguments that arose when a Soviet-themed shirt was worn on campus. Now, imagine an Indian student witnessing colonialist paraphernalia and raising an issue with it, simply to be shut down with an “hey, at least you got railroads, it wasn’t all bad!”. That would be unthinkable.

Millions of people died. Villages were destroyed, families separated, homes burnt down. On a whim of an NKVD officer, someone – no matter whether man, woman, or child – might be killed or sent to the gulag. You never really knew, you would be next. We had to struggle to survive dehumanizing practices and the gradual propaganda-induced breakdown of our society. I say we, because this is not only a question of physical experience – it is one of national memory. I grew up hearing first-hand accounts of survivors, including the story of my beloved grandfather. From brainwashed children betraying their parents to remorseless extermination of our language and traditions, we gradually developed our very own coping mechanism – dark humour – to make sense of the senselessness of barely living. Reading memoirs from gulags, it is difficult to miss the sharp seemingly out-of-place wit, the irony used to explain inhumane treatment. Humour helped us cope and to a large degree it still does.

My grandpa playing with me as a baby. His is the face I see when the USSR is mentioned. Photo: Ieva Salnaite

If dark humour was common in the Soviet Union, what is my problem with a funny t-shirt? Well, when using this dark humour we are simultaneously very aware of the atrocities behind these jokes. This traumatic memory has been instilled within us, by crying and laughing together with the survivors and acquiring an understanding of the suffering. Many Sciences Po students lack this understanding.

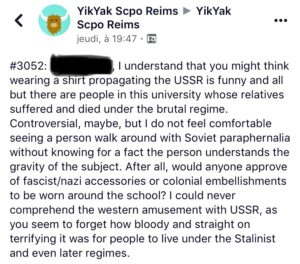

The blatant disregard for personal anguish raised by “celebrations” of the USSR is apparent in the comment section of the Yik Yak post that complained about the shirt. Some people asked how wearing a Soviet emblem on a shirt is different from wearing one of the United States, seeing as both have a history of imperial violence and massacres. Others brushed aside the core of the problem by jumping into a debate over Marxist theories.

The Yik Yak post that started it all.

What they forget is that the USSR symbol was not a voluntary display of membership but an imposed mechanism of cultural homogenization, the absence of which could literally get you killed. Furthermore, human life is not a theory. It is important to make a distinction between the Marxist ideology and the regime itself, the latter being a very poor application of communist beliefs. The USSR, unlike a theory, cannot ever be separated from the brutalities that aimlessly ended lives and traumatised multiple generations.

The example of the shirt is only a small part of a more recent trend of Western fascination with the USSR that I have observed, which extends the romanticised narrative of past events beyond communist ideology and into popular culture. The example is there to illustrate how the West still commonly uses their go-to communist regime as a source for a joke or capitalist gain, without fully accepting possible damage caused. When a French person dismissed my distress on the basis that he found the shirt funny, it made me question why outside spectators (rather than active actors) get to shape the narrative of what is funny and what is history.

To address the elephant in the room: no, I do not advocate banning USSR memorabilia or symbols. It is both useless and counterproductive. The problem is not the action per se but rather the inconsiderate mentality behind it. Instead, I ask for cultural sensitivity. After all, if we have managed to successfully create societal stigmas around cultural appropriation of previously colonized cultures, there is little justification for continuing the disregard for national experiences under the Soviet regime. Sometimes the joke is not worth it.

When I came to Sciences Po, classes on imperialism taught me to look beyond official rhetoric to see humans, their lives and the strength they derived from hardship. Yet I never expected that my national suffering would somehow not be enough.

Cover image by Chloé Joubert @The Sundial Press

Other posts that may interest you:

Discover more from The Sundial Press

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.