by Katarzyna Skiba

“Those who are able to climb up the ladder will find ways to pull it up after them, or selectively lower it down to allow their friends, allies, and kin to scramble up. In other words: ‘Who says meritocracy says oligarchy.’” – Chris Hayes, MSNBC

“A lot of people think big business in America is a bad thing. I think it’s a really good thing. Most people in business are ethical, hard-working, good people. And it’s a meritocracy.” – Steve Jobs

Meritocracy, or the idea that one’s socioeconomic success is determined by their own virtue and hard work, is lauded by pundits, politicians and entrepreneurs alike. Around the world, this principle has been used to credit the wealthy and successful as moral, driven by their skill and desire to succeed, while blaming the poor for their own lack of determination. It falsely inspires those at the bottom of the ladder through political speeches that promise a future where the have-nots will be the soon-to-haves. If they work hard enough for it, that is. In today’s world, where the gap between wealthy and poor has skyrocketed, many are beginning to question these notions. After all, as the rich become fewer and fewer, does that leave the rest of us without virtue? Moreover, does social mobility as it is depicted in these meritocratic ideologies exist at all?

In his film “Parasite,” director Bong Joon-Ho directly examines these questions. He tells the story of a poor family, the Kims, who each swindle their way into a job in the gleaming mansion of the wealthy Park family. Each member of the Kim family displays a cleverness and skill that initially helps them to work their way up the hill and into the Park residence, but no one does this as well as Ki-Jung, the daughter of the Kim family.

Parasite, Bong Joon-ho, 2019

From the very beginning of the film, it is clear that Ki-Jung has developed a resourcefulness that has kept her always looking for the next best opportunity or chance to escape her immediate situation. When her family receives reduced pay for sloppily folding pizza boxes, she tells their boss that she knows about their part-time delivery driver, who didn’t show up as soon as they had a huge order to fulfill. While this isn’t directly addressed in the film, it is possible that Ki-Jung, knowing who the driver was, made sure that he did not show up, leaving behind an open position for herself or her brother. When Ki-Woo, her brother, gets a job as a tutor for the Park family, it is Ki-Jung who photoshops realistic university documents for him to present as credentials, causing her father to ask “Wow, does Seoul University have a major in document forgery? Ki-Jung would be top of her class.” It is clear from these moments onward that Ki-Jung is not lazy or stupid, but rather held back by her social class and the lack of opportunities presented to her, which would allow her to channel her skills.

Parasite, Bong Joon-ho, 2019

Throughout the first half of the film, every member of the Kim family makes their way into the Park house. Ki-Woo, the son, first enters as an English tutor, and upon hearing that Mrs. Park is looking for an art tutor, he recommends a “classmate of his cousin,” Jessica, paving the way for Ki-Jung to pose as Jessica and have an interview with the madame of the family. While Ki-Woo lets Mrs. Park sit in on his tutoring session with her daughter, and waits for her approval, Ki-Jung not only claims that she is an art tutor in high demand, but goes on to invent a position for herself. She is not controlled or visibly intimidated by the Park family’s wealth, and rather than staring in awe at Park son Dah-Song’s supposed “self-portrait,” she invents something called a “schizophrenia corner” present in Dah-Song’s drawings, claiming that he needs immediate art therapy and that for the proper rate, she is the only one who can help him. She turns typical power relations on their head, acting for the position she wants, rather than the one that she has. And in the end, she not only gets a job, but also a raise. All on her first day.

Ki-Woo and Ki-Jung attempt to get an internet connection in their semi-basement apartment, Parasite, Bong Joon-ho, 2019

After her tutoring session with Dah-Song, Ki-Jung is driven home by the family chauffeur. The driver, trying to be polite, insists that he drives Ki-Jung home. She refuses again and again, telling him that she is waiting for her boyfriend at the train station. Thinking one step ahead, she knows that if the driver sees her semi-basement apartment home, she will no longer be able to trick Mrs. Park into believing she is a sought-after tutor. Rather than choosing to fit in with her class or see herself as confined to it, Ki-Jung not only tries to escape it but also refuses to disclose her position on the socioeconomic ladder to others. She is not Ki-Jung from the semi-basement, she is Jessica from Chicago.

When the Park family goes on vacation, every member of the Kim family relishes the time they get to spend in the Park house alone, acting as if it is their own. Ki-Woo goes through the diaries of Da-Hye, the girl he is tutoring. In a moment of peace, Choong-Sook takes a break from being the family housekeeper and naps on the floor, sunlight streaming onto her face from outdoors. Ki-Jung, on the other hand, flips through TV channels while taking a bath, even asking her brother to bring her a bottle of water. She is so convincing, acting like she belongs, and maybe even knowing that she should, that her brother tells her: “You fit in here. This rich house suits you, not like us.” And indeed, there is something about her that stands out. Her brother is the eternal optimist, clutching to the false hope of his scholar’s stone, daydreaming about marrying Dah-Hye and hiring actors to play his parents at the wedding. At the same time, he feels insecure in the Park mansion, and looks to Dah-Hye for approval and to convince him that somehow, he belongs.

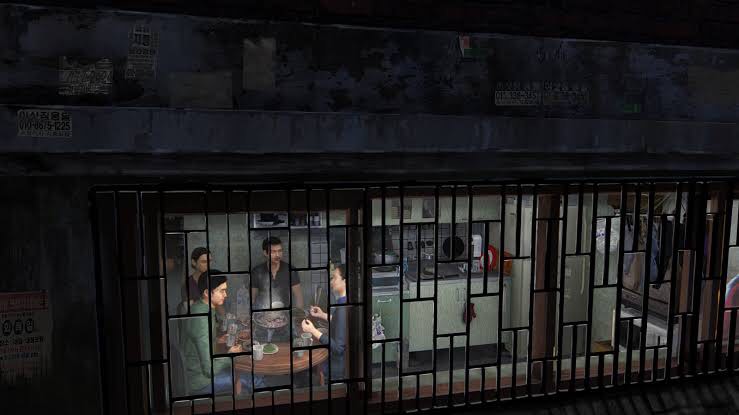

The Kim’s family semi-basement home, Parasite, Bong Joon-Ho, 2019

In the middle of their time alone, the Kim family is interrupted by the news that the Park’s trip has been cancelled due to a storm. After hiding out underneath the Park’s table, the Kims come home and see their semi-basement apartment destroyed by the storm. Seeing all of their possessions floating in shoulder-high sewage water, each member tries to hold on to the few items that hold the most worth to them. The father takes his wife’s tennis medals, a reminder of their former success and holding the potential for hope for the future. Ki-Woo holds on to the precious scholar’s stone his friend brought to him at the start of the film, even as he realizes that it floats – meaning that it is a fake. Ki-Jung however, rather than trying to recover anything, goes into the bathroom, sits on top of a toilet spewing sewage, and, with a dirty hand, lights a cigarette in resignation. Much like she tried to hide the fact that she was poor from the Park family, and even from herself, she almost denies that this is happening to her and her family. She has been so desensitized by their ups and downs that she never takes the time to get upset, or try to save something that is already likely gone or destroyed.

The next day, at Dah-Song’s birthday party, Ki-Jung isn’t relegated to pushing around Mrs. Park’s grocery cart like her father, preparing the tables like her mother, or stuck in the upper room of the house like her brother. She is invited by Mrs. Park herself to be a centerpiece of the party, a guest rather than a servant. She shows up polished as if nothing has changed, despite spending the night sleeping on the floor of a makeshift flood shelter. While carrying a cake in the middle of the party to celebrate, she is fatally stabbed, and her family is left to fend for themselves as their father hides in the house’s secret bunker.

At the end of the film, Ki-Woo comes into contact with his father using morse code, promising him that he will go to university, make enough money to buy the house, and let his father live freely again one day. But rather than ending the film on this optimistic note, when – although unrealistically – we as an audience believe that Ki-Woo could somehow make it, the screen cuts to him in the semi-basement apartment, and we realize that this will never happen.

If Ki-Jung were the surviving figure at the end, the audience would have hope that she would be able to outmaneuver the system, and use her cunning determination to claw her way to the top. By killing off Ki-Jung, director Bong Joon Ho directly attacks this notion of meritocracy, stating that even the smartest cannot escape the confines of their class. In spite of her situation, Ki-Jung found a way to not only make money, but to make extra. Not to grab for the charity that she could get, but to rise to the occasion and claw her way up the ladder. In doing so, she embodies the meritocratic ideal of “pulling yourself up by the bootstraps,” the self-motivated innovator who can push their way out of their situation by virtue of learning the system and working their way toward success. She’s ambitious and rational in a way that evokes the homo economicus, thinking not about any moral consequences of her family’s actions, but rather of what they mean for her own gains and those of her family. If even she and others like her cannot rise up, no one can.

According to Ben Bernanke, American economist and two-time former chair of the Federal Reserve, “[a] meritocracy is a system in which the people who are the luckiest in their health and genetic endowment; luckiest in terms of family support, encouragement and, probably, income; luckiest in their educational and career opportunities; and luckiest in so many other ways difficult to enumerate – these are the folks who reap the largest rewards.”

This conception of the potential of social mobility simply through hard work and determination is not only a falsehood, but a harmful one. According to a 2020 study published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of the Sciences of the United States, “recent birth cohorts [from the 1940s onward] experienced less upward mobility than their parents or grandparents” (Beckfield). A similar study published in the same journal in December of 2019 observes a “long-term decline in intergenerational mobility in the United States since the 1850s” (Song, Massey, et.al.). By 2026, Amazon CEO Jeff Bezos is projected to become the world’s first trillionaire, while Amazon workers remain unable to unionize. With surges in demand due to stay-at-home orders, Bezos saw a 24 billion dollar increase in his net worth, while 1 in 4 American workers have filed for unemployment benefits (Evelyn). In South Korea, where the film is based, “hundreds of thousands of people live semi-underground,” and there is “a growing number of people who live in “gosiwon” or “jjokbang” —flop houses where occupants pay daily or weekly rents for windowless rooms barely enough to squeeze in a bed” (Sang-Hun). And now, around the world, those most affected by the COVID-19 pandemic are not the upper and middle-classes who are able to self-isolate in their homes, but the largely working class essential workers – especially those of color – including bus and train drivers, grocery store workers, and janitors, who must leave for work every day, putting themselves at greater risk of contagion. Just this week, protests over the killing of George Floyd in the US ignited debates regarding the racism and classism that is not only present in the police system; but in fields such as business and the access to resources, among others.

We see that social mobility is falling, the wealth gap is rising, and as much as we would like to believe that the socioeconomic ladder rewards good virtue, it does not. The system is unfair and it is broken, and worst of all, it convinces the poor that it is their own fault, their own lack of skill, and their own laziness that has led them into hardship. It keeps them divided in their individualism, rather than united in a struggle for equity, and diminishes any basis for collective struggle. It keeps them eternally clinging to false and faraway hopes, like Ki-Woo, or fighting amongst themselves for mere fractions of what the wealthiest classes can offer, like the two poor families feuding within the Park’s bunker.

In order to truly offer a platform for change, we must not allow people to exclusively blame themselves for “irresponsibility.” We must not act as though everyone who has boundless wealth has the right to exploit those around them without consequence. And we must work towards a future where everyone has the resources to achieve their full potential.

Sources:

https://www.pnas.org/content/117/1/23

https://www.pnas.org/content/117/1/251

https://www.theguardian.com/technology/2020/apr/15/amazon-jeff-bezos-gains-24bn-coronavirus-pandemic

https://www.cnn.com/2020/05/28/economy/unemployment-benefits-coronavirus/index.html

https://www.nytimes.com/2020/02/29/world/asia/parasite-seoul-south-korea.html?searchResultPosition=3

Other posts that may interest you:

- The Trouble with ‘Ecocide’

- Carbon dioxide removal – hit or miss?

- Local Victories for Turkish Opposition — A Sign of Hope?

- Are France and Japan a Mismatch Made in Heaven?

- A Reflection on Dark Tourism

Discover more from The Sundial Press

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

Its also shown that she wpuld rather use her resourcefulness for get rich quick schemes that. Legitimate methods. I worked hard and climbed up the ladder myself so it can be done but the expansion of welfare incentivizes people not to do such things since they get paid to not do so or use their means on get rich quick schemes that fail and leave them right back where they started.