(c) vectorstock

“Ça va?”

I am sure that many international Sciences Pistes would recognise the utter surprise that comes with the first time a person asks you this innocuous question, and then, without waiting for any response, continues walking.

If I wasn’t a fluent French speaker, I probably would’ve thought that at first glance this expression means “hello” rather than “how are you”. It might be too romantic to think that the question “how are you” conveys a sincere interest in how other people are feeling. However, I still refuse to play the “salut ça va?”-“et toi.”-game. You can bet that this often generates some confusion, especially when I respond “non, ça ne va pas.” Indeed, although no one is always doing well, this question seems to be intertwined with a greater desire to comfort the asker than to actually be authentic. Especially at Sciences Po, it seems that many prefer to say what the other person supposedly wants to hear, rather than express their true thoughts and feelings.

This is a war-declaration on small-talk, and I am here to tell you why it’s urgently needed, and long overdue.

Of course, we don’t always want to share our deepest feelings with that random girl from our history seminar, whose name slumbers in the darkest corners of our memory, lurking since integration week. And of course, many people are introverted by nature and prefer to stay in their personal safe-space. Both of these scenarios are perfectly understandable.

Yet, I am convinced that this is also a matter of socialization, specifically a wide-spread stigmatization of uncomfortable topics and emotional disclosure. Especially in our Western society, the Nietzschean philosophy of “one must either be a wheel and nothing else, or get run over by the other wheels”[1] is terribly wide-spread, and rationality is often praised at the price of emotion and empathy.

But, while this numbness might cover us like a blanket, the truth is that the body enveloped in that very blanket remains an emotional being. No socialization in the world can prevent us from feeling, even if we all build up colossal walls in an attempt to protect ourselves from getting hurt.

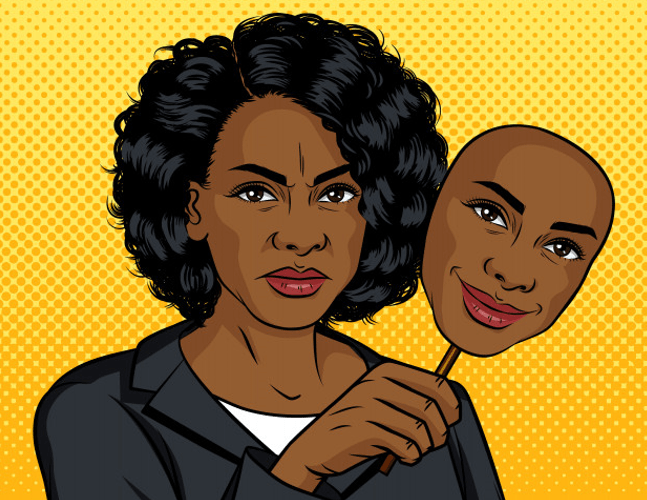

If we now apply this idea to the “ça va” – “et toi” – game, it is clear that we can easily become artificial phantoms of our true selves, mechanically repeating the same blank phrases over and over again. Thus, it seems that at Sciences Po we can talk to a person for two years straight in the court-yard during our desperate cigarette-breaks. But, if someone asked us about who that person really is, we might be unable to say anything concrete about their personality. Indeed, we would know that this person is as tired of readings as we are, and just as hopelessly confused about the modalities of their parcours civique. We could even hazard a guess that they hate the grey weather of this inconspicuous town. Our connection hence consists of trivialized collective experiences framed by our academic or sanitary universe.

What is missing? There is a vast lacuna over the collective experience of simply being human, being emotional – being alive.

So, why does this matter?

Authenticity is sacrificed for the sake of politeness, as we try so hard to avoid moments of potential embarrassment. However, I have found that it is essential to feel this embarrassment in order to overcome not only certain barriers that prevent us from being ourselves, but also the prejudices that we project onto others. Feelings of embarrassment allow us to confront our fears, and help us realize that they exist mainly in our heads, as the product of social norms we don’t necessarily need to adapt to. When we deconstruct these fears together, an enriching, inspiring and honest interaction becomes possible.

If we gain an awareness of the defence mechanisms that we have all built up throughout our lives, it in turn becomes easier to be understanding towards others. Indeed, it is easier to judge a person by their cover than by the numerous chapters composing their life-story. It is easier to be hostile towards someone if they are passive-aggressive, arrogant or superficial, but much less so when we know that they are sad or lonely. On the other hand, it is also easier to be accepted and understood if we reveal our emotions, rather than letting them speak through our defence mechanisms. We can create a more empathetic environment by demonstrating that we are all in this together, and understanding that beyond every toxic behavior lies a hurt inner child we all have inside of us.

Especially in times of COVID-19, as so many of us feel insecure, anxious, or even depressed, let us normalize not feeling good. Scrolling past heavily liked Yik Yak posts about mental health, and their encouraging, thoughtful comment sections, it becomes clear that revealing your fears and emotions does not make you vulnerable. On the contrary, it proves to us all that we are not alone, that we are not failures, and that our feelings are completely normal.

In times of isolation, let’s come closer together. Let’s surrender our urge to be on top of expectations, and realize that these expectations mainly exist in our own minds, not others’.

Let us be authentic, and let us fight the false idea that other people do not want us to talk about our true selves.

And please, if you don’t truly want to hear how I am, then simply don’t ask.

[1] Nietzsche, Friedrich. Book 3, Aphorism #166 in Daybreak: Thoughts on the Prejudices of Morality. Edited by Maudemarie Clark and Brian Leiter, 2nd ed., Cambridge University Press, 1997

Other posts that may interest you:

Discover more from The Sundial Press

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.