By Yanis Makhlouf

The Ukrainian invasion has come to an unprecedented fever pitch after Russian President Vladimir Putin placed Russia’s Strategic Deterrence Forces on a new status of ‘high alert’ on the 28th of February. The potential showdown between NATO and Russia might incite a new missile crisis as the greatest military confrontation in Europe since World War II. The population’s near-amnesia of the height of the Cold War and the greatest carnage in human history makes us vulnerable to a crippling underestimation of the ongoing crisis.

Despite scholarly scepticism around the idea of the “lessons of history,” it can help us understand long-term historical trajectories and the complexity of the present.

From the Sudeten Crisis to the domino effect of alliances in the weeks leading to World War I or even the attack on Pearl Harbour as a reaction to the US oil embargo on Japan, there is no lack of historical analogies to use as a point of comparison with the situation in Ukraine.

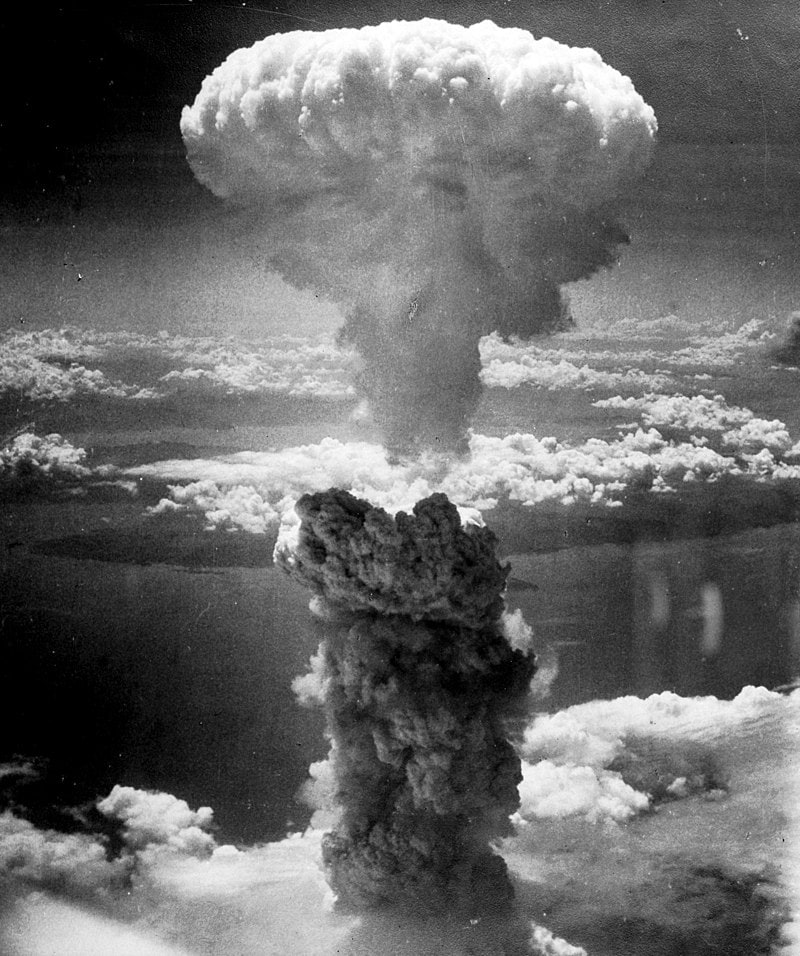

The past is very much shaped by our understanding of the present but investigating the past is key, especially when the stakes are so high. However, this is not solely about history – since the advent of nuclear weaponry, we live in a world in which a few individuals have the capacity to bring the apocalypse on Earth and end our species for good. Of course, the idea that there’s a red button that a head of state could just push on their desk is deeply flawed and a complete misconception of the security procedures surrounding nuclear arsenals. Nevertheless, the risk of massive escalation is not that far removed; I do not want to cause panicked alarmism but merely warn of the risks of an uncontrolled escalation.

NATO and the United States did miss significant diplomatic opportunities with Russia ever since the fall of the Soviet Union and could have adopted a more decisive approach to deter further aggressive actions ever since the invasion of Georgia. Uncertainty and ambiguity vis-à-vis Russia did not help to cool down tensions. No one can say which course of action if any could have completely prevented the invasion, but the failure of deterrence by NATO should create serious questions about power projection and the foreign policy of its most prominent nations.

Ukraine deserves to be supported but such action requires an unfortunate and somewhat dispiriting realisation in the West. The margin of action is very limited; the tightrope is very thin between addressing Russia’s action with necessary severity and an escalation of the conflict that could start a disastrous war. Even if a conflict between NATO and Russia were to limit itself to conventional forces, the human cost would be horrific and cause untold suffering on all nations involved.

No one can pretend to know about Russia’s ruling circles and what goes on in the mind of Putin anymore. The speech he gave announcing the invasion had an ideological component that went far beyond security concerns over NATO expansion and cannot be understood only in the framework of realist theories of international relations. In the past two decades Russia made significant diplomatic gains which could very well be jeopardised by this expansionist move and make once amenable nations more suspicious. Putin’s ruthlessly pragmatic approach allowed Russia to take the upper hand in Syria, expand influence in Africa, establish a new relationship with Turkey based on practical interests, exploit favourably its status as Europe’s gas supplier, and advance its pawns in Ukraine while withstanding US and EU sanctions. In spite of previous very aggressive actions like the invasion of Georgia in 2008 and the annexation of Crimea in 2014, Russia had made its own brand of ruthless pragmatism and realpolitik, framing its foreign policy in a realistic and strategic framework.

However, when the president of the Russian Federation calls for a “denazification” of a country like Ukraine which was not spared by the horrors of national socialism, uses fiery nationalistic rhetoric, and embraces Russian imperialism and panslavism of old, there is reason for concern. This crisis from the very beginning was about much more than Ukraine or Donbass specifically; it is the stress test of the relationship and balance of power between the Atlantic Alliance and Russia. A test the West has failed.

Putin’s move on nuclear annihilation could be a bluff… or not. It might be a sign of desperation at the sight of strategic failures in an invasion clearly not going as planned. Putin’s desperation could be interpreted as a good sign, or perhaps should make us terrified of what heightened emotions could lead the warmongers in Moscow to do. The threat is serious. Whenever each battling power has the capability of destroying the planet several times, risk looms. The luck of human civilisation so far has been that cold heads have prevailed, but this is by no means a given.

The failure of deterrence has placed the entire world at risk and created a crisis with no clear resolution that would avoid both a massive military with Russia and the fall of Ukraine. To think that Putin would not risk nuclear war is a grave mistake. Vladimir Putin is part of a generation that was raised under Soviet propaganda and in the shadow of the Great Patriotic War’s memory. Putin and all those who surround him have grown up with stories of the untold suffering experienced by the Soviet Union during World War II and the spectre of an ideological fanaticism that would go to any length of sacrifice to achieve its objectives, even if that means accepting the risk of self-destruction. The risk of nuclear war seems to be low for now, but the road to escalation is short. Despite the scenarios drafted by general staffs all across the world since the 1950s on tactical uses of nuclear weapons, the destructive potential of the technology makes containing any conflict involving them to a “limited scale” almost impossible.

Even economic sanctions ought to be seriously thought about. Russia cannot be treated like Iraq or Afghanistan. Putin is no Saddam Hussein, Bachar Al-Assad, or Kim Jong-Un. Isolating a major military power is not the same thing as crushing a backwater dictatorship in the Middle East or imposing sanctions on the Hermit Kingdom. Yes, NATO is by far the mightiest military alliance in history and yes, the combined economic power of the European Union and the United States dwarfs Russia’s. However, this asymmetry is not as pronounced on the side of the West as it is against basically any non-nuclear power.

I do not pretend to know the right answer to this crisis and there might be none.

This uncertainty is precisely why an underestimation of the nuclear threat is so fatally dangerous.

[Image Source: https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/e/e0/Nagasakibomb.jpg]

Other posts that may interest you:

Discover more from The Sundial Press

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.