By Diana Piper

My hair is longer now. Not particularly long, not long enough to drape over a chair, hook on a pant leg, or act as an “it’s a bit too obvious, but otherwise it’s brilliant” idea for a party trick. But it has become long enough for me to notice. It has also straightened and darkened, turning it into a heavy honey-blonde curtain — I pull it up whenever I find a hair tie, though that task proves excessively difficult at times. Regardless, it makes me different and slants me a different way. Yet my intention for this difference remains obscure: did I decide this on the useless vanity of my intuition, or did I ignore this, wishing in vain for it not to happen? Did I reserve my haircut for hors de France? Was I guarding my hair from my new residence, from upkeep in my new residence? All I know is that it is longer now, as long as it was two years ago.

The length of my hair is the one change since coming to Sciences Po I can establish, and even that change gives me the same face as the one I had at 16. I did modify myself more dramatically — I got a nose piercing. But I do not mind that. I can better understand a mundane change, a nothing-change. A change that means nothing and is nothing – so you can secure it. Of course, I cannot secure the intention, but I can secure its occurrence. Its coincidence with the movements of the planet and the body. Its egoism, pseudointellectualism, and self-replicating suicidality. My hair has become longer, and I can give it more words and make it big and make it mean something.

To give more words is to give more of yourself: I am Diana Piper, Swedish, 18 years old. I lived in England for ten years and California for seven. My family is medium size, all Swedish, mostly mentally ill. I am mentally ill: depression, anxiety, perhaps a mood disorder. I am a first year at Sciences Po and will transfer to UC Berkeley after my second. I have tried several times to transfer earlier. I will likely not transfer earlier.

Inertia surrounds these facts. Years run long, countries keep their names, families keep their faults, and students keep their schools. But something campaigns against this — I kept my hair the same, and it grew longer. The action of non-action, movement of non-movement, feeling of non-feeling. When your ground crowds you, draws you into a square, you push against it, dig your toes in the crack. The body resists. It forces you to change.

In mentally ill and neurodivergent circles, change happens both never and constantly. It works as an equilibrium, an organ that portends something illegible: an appendix. It appears vestigial, minuscule, hanging off the end of the large intestine, waiting to be cut. An umbilical cord after birth. Yet it also appears to add a level of defense, perhaps a well of helpful gut bacteria. We do not know. The body has no obligation to explain itself to its owner, only to keep that owner alive. The universe has no obligation to explain itself to its inhabitants, only to act as a place to be inhabited. Scientists try to make them both explain anyway.

I suppose this essay is my own vain attempt to explain, a science-adjacent jab at what sustains me, the environment of which I cannot absolve myself. My sickened group, my leveled group, my adored group, my artistic group, my resolute group. The farcical community which adjoins me. The one exists simply because it shouldn’t — establishments, schools, hospitals, workplaces claim to take care of the ennui that they caused in us, but they cannot. When the gridlines of reality repel you, you tack onto others. You pool up, a falling, three-beat, Mission-Impossible rhythm. You step on one person’s back, then bend so that someone can step on you.

We clean each other’s apartments, cook food for each other, help each other with homework, host each other when sleeping in the same bed is impossible. Pairs form — the depressed and the anxious ones. One speaks in tremors, eyes fixed, hands fiddling, lips bitten. The other speaks in sighs, eyes disengaged, hands stroking their thighs, mouth open. They loop around each other and themselves, a whorl of moods and mentalities and misgivings. They speak their oblique thoughts directly — they do not lie, only reveal their mind’s dishonesty. No one appreciates each other. Appreciation cannot accommodate need.

Mutual aid creates a unity greater than enjoyment. It moves as hair moves: rooting down, growing longer. An immediate reaction. A bodily reaction. Boring, obvious, self-effacing, self-contained. It is upkeep necessary for some but not for others — in fact so unnecessary for others that establishments do not validate that upkeep. Schools do not give accommodations, doctors do not take it seriously, the government does not consider psychologists’ charges as included in free health insurance. If you cannot attend class because you cannot leave your bed, you must schedule and attend a doctor’s appointment, obtain a medical certificate, and report your absence within five days. Your sickness prevents its justification. Your only recourse? A group of fellow depressives, ready to push you out of your episode.

Mutual aid trespasses on friendship. The word means little — the hugs, compliments, outings, and pictures of outings are not important. You need to fill up a carnal need first, the need to function as a human here does. You must eat. You must leave your bed. You must go to class. You must keep your appointments. These musts come before manufacturing social interactions. The mutual aid circle becomes live-in, an addendum to yourself. It moves into, not around. Love, friendship, contentment will come later. First, you need someone who will force you to put on socks.

My friendships are a partial action. They overlap my mind but do not sink into it. I still love my friends deeply — I know how they smell, how they arrange their appearance, how they laugh, and what they laugh at. But my illness caps my expression of this love. My friends cannot release me and I cannot release them. Thankfully, mutual aid can poke a hole, lessen the pressure. I don’t thank them enough and neither do they. But we help one another.

My hair is the same length as what I had at 16. My face is the same. My family is the same. My languages are the same. My needs are the same. This time, though, mutual aid has come, kicked in, hands and feet ready, tongue by the teeth. The movement has deblocked the individual, the sole neuroses appertaining to the sole person. It has become bigger than relationships because relationships are only links between individuals. Mutual aid is a necessary, quiet movement – just like the growth of my hair.

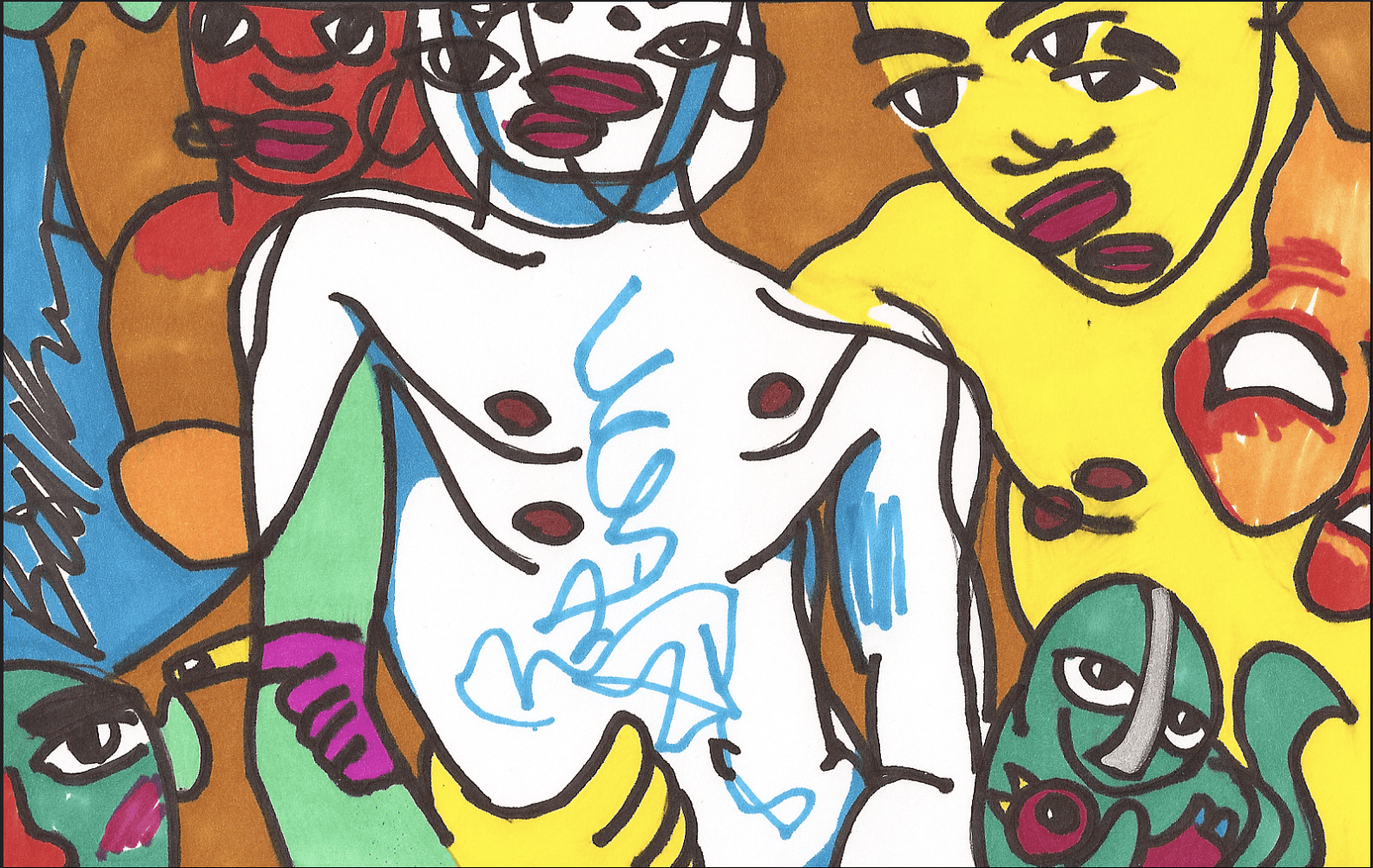

Artist statement: “This piece is a self-reflection on mental illness in university and the mutual aid groups that form from it. I wished to write this in order to reveal the strength of support within a community, especially when the rest of the world offers unhealthy solutions to that community’s problems or simply shuts out the community itself. I hope this serves to reveal another side of Sciences Po and to demonstrate to mentally ill students that there are others willing to help.”

Other posts that may interest you:

Discover more from The Sundial Press

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.