By Alyssa (Yueran) Sun

A head of lettuce lasted longer than the British head of government.

The absurdity of the situation makes it seem more like a sitcom than real life. But alas, it is real.

In The Economist’s article “Liz Truss has made Britain a riskier bet for bond investors,” the author estimated that between her formal appointment as Prime Minister on 6 September and the implosion caused by the announcement of the “mini-budget” on 23 September, Truss’ grip on power lasted no more than 7 days, deducting the 10 days of mourning following the Queen’s death. The shelf life of a head of lettuce is 7-10 days.

Inspired by The Economist’s shrewd comment, on 14 October a British tabloid named The Daily Star started a live stream in which a lettuce was placed next to a portrait of the soon-to-be-former Prime Minister. “Will Liz Truss outlast this lettuce?” the newspaper asked in the video. She didn’t.

Setting the record with a 44-day-old premiership, Liz Truss is the most short-lived Prime Minister the UK has ever seen. Now, as the UK has ushered in its third prime minister in three months, it may be worth taking a look at how Liz Truss bravely took over a British economy in crisis, and adamantly smashed it into smithereens.

Timeline:

5 September — Truss wins Tory leadership contest.

6 September — Truss is formally appointed Prime Minister by the Queen and appoints Kwasi Kwarteng as Chancellor of the Exchequer

8 September — The Truss administration announces plans to freeze energy bills

23 September — Kwasi Kwarteng announces the fiscal policies of the Truss administration, dubbed the “mini-budget”, which aimed to stimulate the economy, mainly through a series of drastic tax cuts, amounting to £45 billion in total.

From 23 September onward

- The pound starts plummeting

- Reactions in the gilt market (government bond market)

28 September — Bank of England intervenes heavily in the gilt (British government bond) market

2 October — Truss acknowledges mistakes over the mini-budget, blames Kwasi Kwarteng for abolishing the top rate of income tax without discussing it with the cabinet and insists on her tax-cutting plans

3 October — The Truss administration restores the 45% top rate of income tax, contrary to what was announced in the “mini-budget”

14 October — Liz Truss fires Kwasi Kwarteng and takes a U-Turn on her attitudes

17 October — Jeremy Hunt reverses the tax plan and slashes energy price freezes.

19 October — Truss says “I am a fighter, not a quitter” after being attacked by the opposition during Prime Minister’s Questions (PMQs)

20 October — Truss quits

A Rocky Start

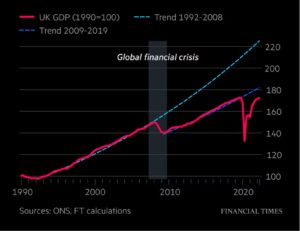

Taking the British economy on one’s shoulders when it has been stagnant for more than a decade is no easy task. As demonstrated by calculations by the British Office of National Statistics (ONS) and the Financial Times, the UK has yet to recover from the global financial crisis of 2007-09. Productivity and real income have been left flat for the years that followed. This is the case for many other western countries, but the pace of productivity growth in the UK has been exceptionally slow among other G7 countries.

This graph from The Financial Times shows that ever since Brexit, real GDP growth has been stagnating in comparison to what’s projected based on trends prior to 2016.

Britain’s decision to exit the European Union took a large toll on the British economy. The UK is expected to be hit by tighter financial conditions, weaker confidence, and higher trade barriers and restrictions on labour mobility. Using data from the ONS, a map of business investment from 1997 to 2022 shows that business investment ceased to grow after Brexit.

Needless to mention, COVID delivered another heavy blow to the British economy. Investment plummeted, the GDP saw a historically large decline, and the budget deficit rose to 15.1%—a peacetime record. Due to both COVID and Brexit, a severe labour shortage also ensued. Companies, desperate to hire, have been offering up to 20% rises in wages, yet failing to keep up with the pace of inflation.

To make matters worse, this year’s Russo-Ukrainian war has disrupted the supply chain, driving up energy and living costs, thus aggravating cost-push inflation (inflation caused by a drop in the purchasing power of a currency due to rising living costs) in the UK. The latest estimates show that prices in the UK are 9.9% higher compared to those of a year earlier. The UK isn’t alone in suffering from the economic repercussions of the war in Ukraine. Estimates for Germany, for instance, show that its inflation rate was up to 10% in September. Nevertheless, many of these economic issues are UK-specific.

Amid a financial crisis, facing wavering confidence in the UK economy and a fracturing Conservative party, prospects for her regime seemed dim. Having won by just a slight margin of victory, obtaining merely 57% of the votes in her race with Sunak, Truss needed to impress her partisans and the British people with a strong response. But her challenges were enormous. On 5 September, Financial Times commentator Robert Shirmsley poignantly remarked, “Liz Truss should enjoy the next 48 hours. They may be the happiest of her premiership.”

Unfortunately for Truss, the prediction turned out to be accurate.

A recap of Truss’ disastrous financial policies

As we can see from the timeline above, the ‘mini-budget’ is what sent the British economy and Truss’ prospects speeding downhill.

In a nutshell, the Truss administration planned to cut the basic rate of income tax, reversing the tax rise for the wealthy and businesses, lifting the cap on banker’s bonuses, a “permanent cut” on stamp duty (a tax levied on single property purchases), reversing the projected rise in national insurance, and “carpet-bombing” the country with investment zones with lower taxes and lighter regulations.

In addition to that, an energy bill freeze, announced on 8 September, which is an attempt to address the rise in energy prices and “let people know help is coming,” would entail £60 billion pounds of extra spending within the next 6 months only.

When journalists pointed out that her tax cuts disproportionately benefited the wealthy, she argued that it’s not about redistribution, but about “growing the pie so that everyone gets a bigger slice.”

Ambitious and confident, Truss seemed to be blind to the glaring fact that the British government is already heavily indebted. Her belief that tax cuts will pay for themselves in the long run under the form of boosted economic growth, does not stand on empirical grounds, as data from the International Monetary Fund (IMF) show that there is no clear correlation between tax burdens and prosperity.

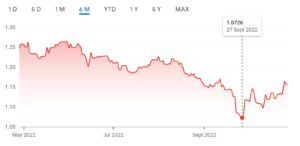

With a drastic plan backed by little theory or empirical evidence, Truss also didn’t have any clear plans to fund her agenda. Expecting a dramatic increase in government borrowing, interest rates rose, leading investors to sell off British government bonds (gilts) massively. As a result, gilts “swung more within a day than they had in a full year for the past five years,” imperilling British pension funds, as they rely on bonds to liquefy their assets and provide cash to pensioners. On 28 September, the Bank of England had to urgently intervene, buying a large number of bonds and postponing its scheduled bond sell-off. While the bond market was plunged into mayhem, the value of the pound plummeted to a record low, as investors, foreign and domestic, lost faith in the British economy.

This graph from Google shows how the value of the pound sterling relative to the US dollar plummeted to a record low on 27 September, closely following the announcement of the mini-budget.

U-Turn and Subsequent Resignation

Failing to carry out almost all her promises, Liz Truss had to give in. On 3 October, she restored the top rate of income tax. On 14 October, she fired Kwasi Kwarteng, her chancellor and closest ally, and replaced him with Jeremy Hunt. Later, she apologised for her policies.

Truss’ U-Turn, however, hardly saved her month-old career. Hunt did not hesitate in pointing out that Truss and the former chancellor “made mistakes,” and cancelling most tax cuts planned in the mini-budget, a move that basically placed his authority above that of the Prime Minister. More importantly, as tax cuts were part of her campaign promises and the centrepiece of her growth policies, her reversing the entire agenda under pressure made it impossible to trust her judgement. During Prime Minister’s Questions (PMQs), Labour leader Keir Starmer ruthlessly mocked: “What’s the point of a Prime Minister whose promises don’t even last a week?”

Following her resignation, Rishi Sunak was quickly elected as Britain’s new PM. Nevertheless, the British are impatient—polls show that Tories’ public support is now around 20%, whereas that of Labour’s is over 50%.

With a broken economy, political unrest, and loss of Britain’s reputation for stability in the international community, Rishi Sunak will have to demonstrate exceptional talent just to last long.

Other posts that may interest you:

Discover more from The Sundial Press

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.