By Rysha Sultania

Uncredited image

My window directly faces Sciences Po. Thus, on a normal day, whenever I look out, I often observe students rushing to Paul for a hurried lunch, exchanging greetings or clamoring over fallen backpack contents as they find their student IDs to show security. From sullen scurrying every early exam-morning to electric excitement post-finals, I’ve gotten used to Place Museux’s noise engulfing me. Perhaps the only time my window sees Sciences Po quiet is on Sundays or in the wee hours of the morning.

Except today, when I woke up at 5 AM (thanks PoliSci midterm -_-) and for the first

Photo by Aliya Hirji

time, I wasn’t alone.

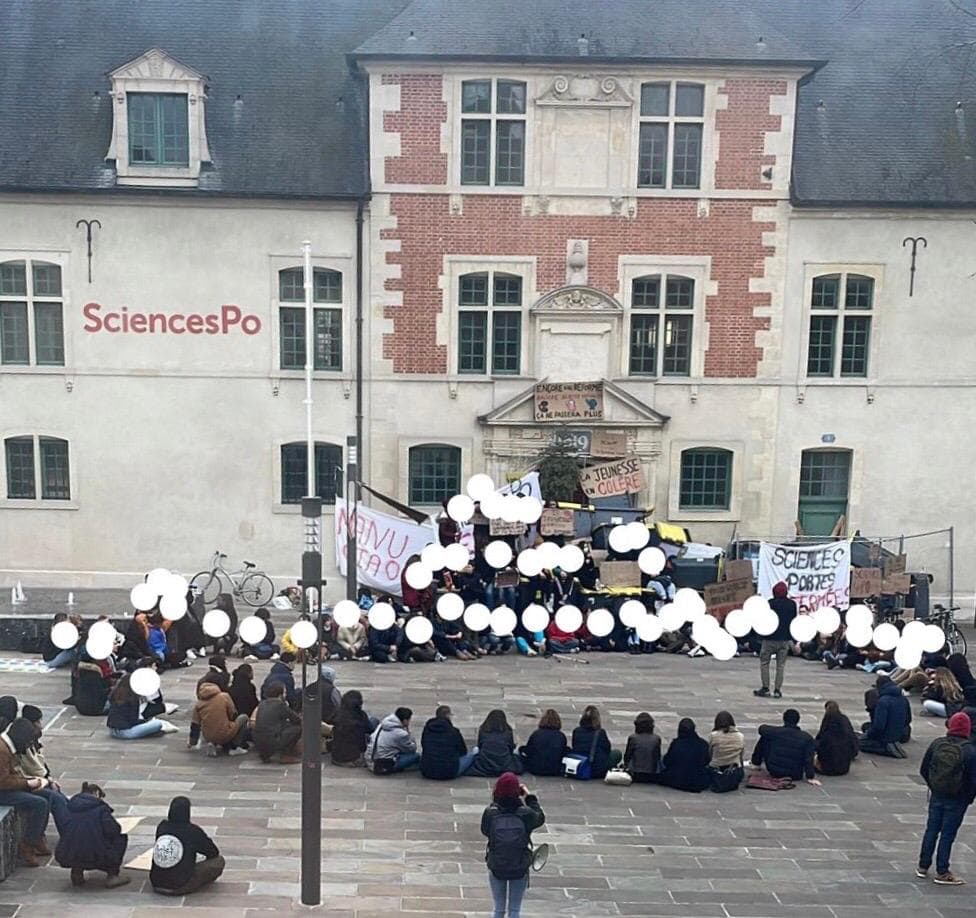

Looking out my window, I saw large group of around 25 collecting trash cans, arranging them in front of Sciences Po’s facade, interspersed with banners of “Sciences Portes Fermées“ and “Manu Ciao,” in preparation for a day-long blockage of the school to protest the lowering of the retirement age from 64 to 62 in France.

Today’s blockage, and over a month of nation-wide protests, has had undeniable effects on student life at Sciences Po—SNCF canceled trains, classes shifted online, and some lucky 1As got out of an Environmental Justice midterm. These effects, caused by backlash to French governmental reform, have thus had non-French impacts on Sciences Po and its internationals, who make up 50% of its student body.

View from my window by Rysha Sultania

While the issue has gained global interest, it has largely been framed as a matter of culture (nearly every New York Times article I read had some allusion to France’s history of protest).

And so, if protesting is so inherently French, was today’s blockage at our diverse Reims campus inclusive of Sciences Po’s non-Frenchness too? What did international students think of it and to what degree did they get engaged in the movement? To probe this issue further, I interviewed a few students, international and French, and gained some insight about their perspectives on today’s events.

On asking Juliette Pieraerts, a 2A from France who has organized several protests at Sciences Po before, what she thinks of the impact of Science Po’s diversity on how this particular blockage has been carried out, she points out, “The diversity of Sciences Po hasn’t honestly brought a lot of change or impact on this movement. Most of the international witnesses have

Photo by Juliette Pieraerts (1)

just come to help out and understand what’s going on but they obviously haven’t really changed the course of the movement. Obviously we’ve tried to be accessible and engage everyone, circulating English pamphlets and explaining why students, especially internationals, can’t access the library today. It’s not because we like to skip class but because this protest is a traditional way of doing things in France when we disagree with our government”.

On this note, I asked whether international students have understood this French exceptionalism to the art of striking, which can often feel just as frustrating to follow as the French problématique format in our essays.

Juliette’s friend, Audrey Bonn, jumped in here to appreciate the internationals’ efforts to actually get involved despite not fully understanding the French-ness in this revolutionary movement: offering their apartments in case something is needed or bringing out food for those protesting. Juliette adds, “However, in France, it’s just easier to be involved because you grow up seeing protests. Like even the 2018 Yellow Vests. Even if you don’t participate, there’s a lot of information about it, you see the manifestation happen around you, and it’s also very organized. So we’ve tried to make information accessible to everyone to understand why we’re protesting but really, this is our way of telling the government that they’re not listening to us. It’s just the French way and how we’ve always done it.”

So, then, is there after all an exclusion inevitable in today’s blockage, just by virtue of not being French? For one French student I interviewed, who interestingly has studied and grown up in the United States, despite her primary socialization and mother’s positive portrayal of protests, the nature of how much impact civic engagement actually has in America made her initially regard French protesting as “too radical.” Despite this, she adds, “Being in France and seeing protests like these however make me more critical of the US as a role model for democracy and social action as a whole.”

To me, this quote really highlights the real-life applicability of state-citizen relations in advanced liberal democracies, a fact we often study comparatively in our EURAM courses at Sciences Po. In the words of Makayla Gubbay, a Columbia-Sciences Po Dual BA student, “France’s spirit of striking is a lot more unified than America’s. The ability to shut down the economy to this extent isn’t seen as valuable or even possible in US society. Overall, there’s a lot more promise for strikes in France because of the spirit of civic engagement while political participation is only through institutions and voting in the US.”

In fact, through these interviews, while internationals seem to appreciate today’s blockage as a learning opportunity, the extent of diversity also provided no shortage of potential critiques, especially in the spirit of how international perceptions understand further social inequalities within this movement.

According to Sophie Hawthorne, a 1A EURAM from Texas, “A lot of news outlets internationally are coveringthis is

Photo by Juliette Pieraerts (3)

sue as a reflection of French culture and the commitment to work-life balance but they forget to mention that real people, women, working classes are being affected too. As an American, I see this reform as a way for France to confront their own inequalities and overcome their belief in absolute equality through a united citizenry that protests together. Ultimately, I’m curious if these protests will make France move from a conception of equality that focuses more on equity.”

Although all chants and posters today are in French, the protest has been far from exclusive, and all day long, my phone has been ringing with updates on the student group chat, and many internationals have volunteered their footage and photographs to supplement this article. In my eyes, this consideration for diversity is definitely valuable to Sciences Po’s political fabric as a whole. While most Sciences Pistes reveal an acknowledgement of the French sentiment to protest, they also simultaneously view the utility in the French citizen culture as one that engages itself in government accountability and personal responsibility.

Photo by Min-Jee

Thus, as students of one of the world’s leading political science universities, blockages like today’s could be acute ways of bridging cultural gaps in how individuals perceive drivers of social action. In many ways, perhaps such protests illustrate a lot more about institutional change, path dependency and democratization than a 2-hour Political Science midterm ever could.

And for that exact reason, and none other, maybe we strike again this Saturday?

Note: While all quotes from individuals are direct, some have been shortened or reformulated for clarity.

Other posts that may interest you:

Discover more from The Sundial Press

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.