‘They mean well,’ begins every polite explanation of an individual’s incompetence.Whilst this usually takes a trivial context, sometimes the road to hell is truly paved with good intentions. Nothing fits this more than the ‘voluntourist,’ a type of tourist who engages in voluntary work abroad. Embarking on a thousand-euro volunteer programme abroad, the voluntourist hopes to make a difference. However, they are rarely skilled and often ignorant about the potential harm of their actions.

‘Voluntourism’, a combination of the words volunteering and tourism, refers to a type of tourist who engages in voluntary work abroad. Although this voluntary work may reap positive impacts, the true intentions of the voluntourist differ from that of the volunteer. Rather than purely travelling for the sake of responding to the needs of others, the voluntourist is also attracted by travel and social media content, virtue signaling throughout the entire process.

The voluntourist’s attraction to travel, rather than volunteering, may create a disconnection between the voluntourist and their cause. They may lack adequate cultural understanding, language knowledge or even the necessary skills to truly help the recipient community.

Meanwhile, voluntouristic behaviour such as taking photos of members of the recipient community and uploading them to social media, may even be a threat to their safety and wellbeing, especially in a context of violence and persecution.

In this case, it is necessary to distinguish between volunteering and voluntourism. Volunteers may also be sufficiently equipped to respond to the needs of the community and make a genuine difference, such as by offering medical or educational services.

On the other hand, the voluntourist may lack an understanding of the real needs of the recipient population, and may even be unable to identify an adequate host organisation. For instance, one of the main beneficiaries of volunteers from abroad have historically been orphanages, an institution high income countries such as France have almost entirely abandoned due to decades of research proving a higher likelihood of child abuse, cruelty, or neglect. Research by Lumos, a charity working against the institutionalisation of children, has found cases of children being malnourished, trafficked, and even sold for adoption in wealthier countries.

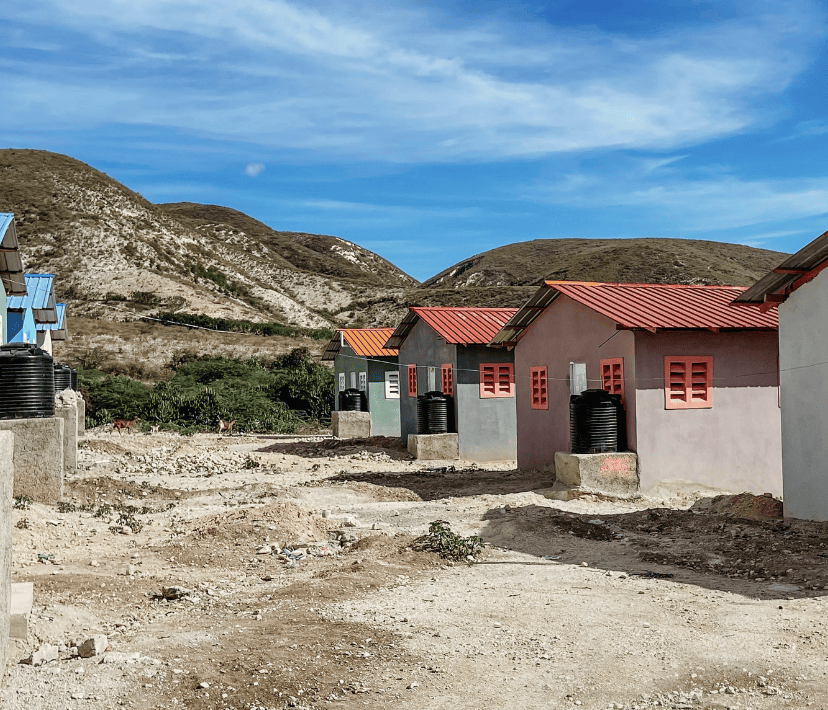

Meanwhile, orphanages greatly profit from volunteers and donations, with one orphanage in Haiti collecting an average of $100,000 per child per year. The majority of this lines the pockets of the corrupt director. Most disturbingly, there have been cases of orphanages deliberately keeping children looking malnourished to attract more donations.

The growing industry of voluntourism also feeds into a neo-colonialist system, where individuals of the Global North may begin to view those from the Global South to be ‘in need of help’ and unable to respond to their needs without the assistance of the Global North. Also referred to as ‘white saviourism’, as coined by Nigerian-American writer Teju Cole, voluntourists from the Global North may assume a superiority of knowledge which they believe will equip them to ‘rescue’ their non-white recipient community.

Needless to say, this is not the case.

As stated by Tina Rosenberg, ‘voluntourism may be fuelled by noble feelings but it is built on perverse economics.’ Volunteers offer a stream of income for such institutions, keeping them open and keeping them dependent on workers from abroad, the short-term nature of whom often leaves abandonment issues amongst children. Meanwhile, as the employment of local workers would cost money rather than raising it, local employment is limited, preventing economic self-sufficiency.

The dependence on donations from volunteers also shifts such institutions’ focus from helping the local area to maximising the experience of volunteers. This is startlingly clear in The Hope of Life Project in Guatemala, where volunteers can be housed in air-conditioned suites with private bathrooms, whilst housing dedicated to disabled children allocates between 8 and 11 children to each room.

On the other hand, most organisations would often benefit more from the equivalent financial donation than the volunteer’s actual labour. This can be seen by a project in Haiti where volunteers built a school, which ultimately lacked the funds for teachers. Meanwhile, the $2000 spent on a volunteer’s week-long trip could have funded a village teacher for four months.

Conversely, the quality of labour may not even be satisfactory, due to the lack of formal training required. One American volunteer in Tanzania admitted that the volunteers were so unskilled at construction work that each night local men would have to secretly rebuild the accomplishments of the previous day.

Each year 10 million voluntourists go to the Global South to fund an industry worth over $2 billion. However, rather than funding systemic change in developing countries, vast sums of money are being spent on maximising the experience of foreign volunteers and endowing corrupt institutions , which they may then proceed to flaunt on social media. Their intentions may be honourable, but voluntourists are perpetrating a system of corrupt institutions and economic dependency.

Besides, no matter how flashy the advertisements for volunteer programmes, structural inequality is hardly a glamourous affair.

Other posts that may interest you:

- Insight into the Warwick Economics Summit: A Discussion on the UK’s Economic System with Sir Howard Davies

- La grève des scénaristes et des acteurs: Hollywood en péril ?

- A forbidden fruit — nourished in shadows,

- Paris, December 21

- At your mercy at the coffee shop

Discover more from The Sundial Press

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.