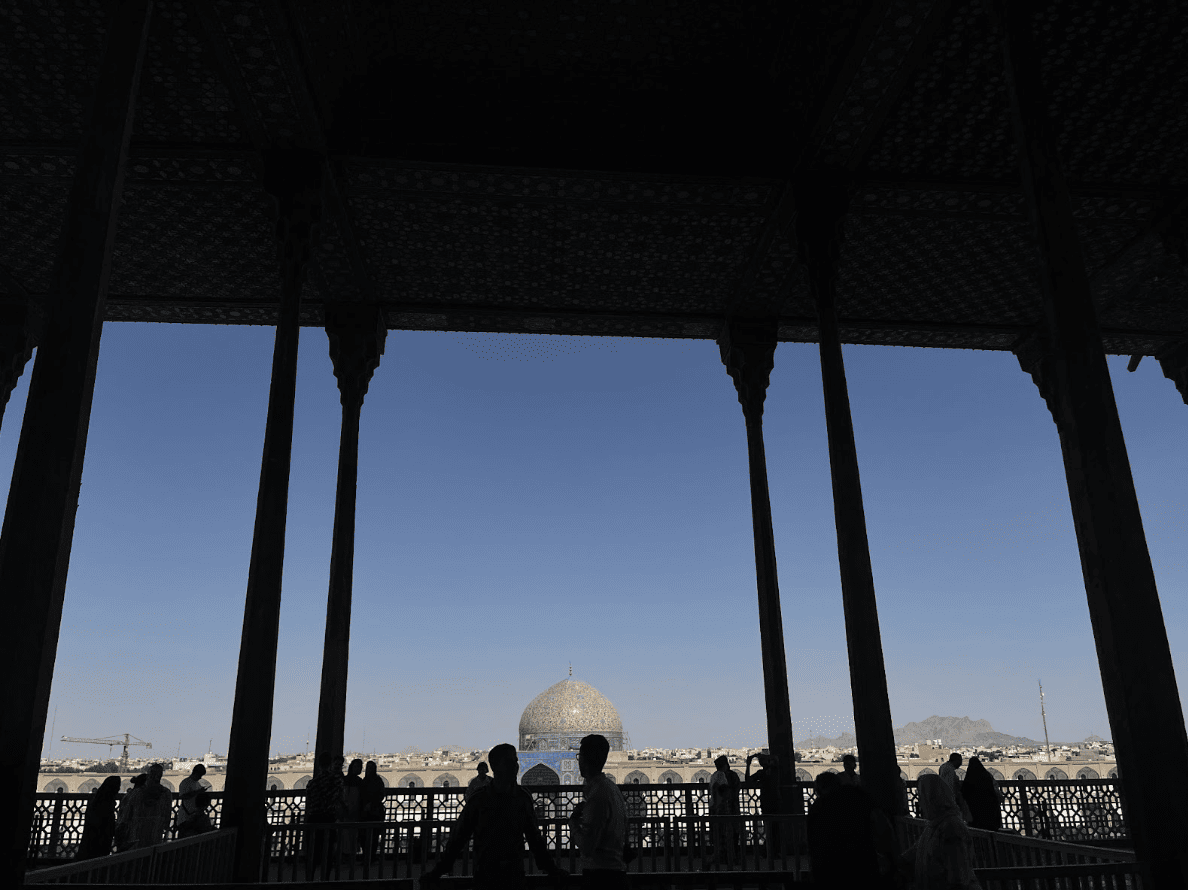

(In Esfahan, 2023)

Two months ago, Fariba Adelkhah, a Sciences Po researcher specializing in Contemporary Iran finally returned to France after four years of detention in Tehran. Her release serves as a crucial victory for academic freedom at Sciences Po. While Iran may seem daunting to some, last summer I embarked on a 15-day backpacking trip. I was keen to peel back the layers of this enigmatic nation, to witness first-hand the realities behind the veil of Western politics and media portrayals.

“[Iranian Customs] don’t have a sense of humor,” said the check-in lady at Charles de Gaulle as I boarded my flight to Iran. While she was laughing, I was concerned instead of amused by this joke, because I had not yet bought a return ticket. Indeed, my lovely family and friends chided me for my recklessness, but they also knew I enjoyed these spontaneous adventures.

Upon arrival, the capital city of Tehran presented a dichotomy that initially overwhelmed me. The prevalence of strict laws governing personal attire was palpable, a stark reminder of the tragedy of Mahsa Amini and the broader implications of such restrictions. Gradually, I got used to seeing women in chadors, yet I was curious to see the ones who “rebelled.” To my surprise, my search was quite easy because the rebels seemed to be everywhere. Women who dressed fashionably without a hijab could be spotted on the metro, on the streets, and in restaurants. Interestingly, panic and unease momentarily washed over them when someone with a police badge came close. They would then assimilate themselves back into the crowd. The subtle defiance, a quiet refusal to adhere to stringent religious norms, was their way of pursuing personal freedom within a restrictive system.

“My religious belief has taught me to also respect others’ will and freedom,” said a Muslim taxi driver in Tehran after I asked him about his thoughts on the hijab. He sighed and pointed at the enormous portrait of Ali Khamenei, their unpopular supreme leader, referring to him as “one of the problems of our country, our Iran.”

Moving beyond Tehran, as I traversed through smaller cities like Kashan and Yazd, I noted that the rebellions ceased to exist. Fewer women would show their hair, and instead more adopted the jilbab, which covered the whole body. I was not surprised by this, because I, the only foreigner present in the grand bazaar in Kashan, had already attracted an overwhelming amount of glances, a testament to the challenge of deviating from the norm in less populous areas.

In Kashan, a tour guide, proficient in Chinese and fluent in English, piqued my interest. Despite his historical accounts lacking accuracy, his perspective on life in Iran satisfied my curiosity. He was forthright about his disapproval of the government: “The government is crazy… I don’t agree with what they did to people…” His perspective was a rare insight into the lives outside Tehran, often underrepresented in the media.

This sentiment was echoed in Isfahan, where a guesthouse owner, having experienced life in Canada, expressed her frustration: “Yeah, fuck them, religion is an excuse for them to make profits.” She shared stories with me in which some people made a decent living out of reporting people to the government and moral police. “They bought a big nice house by reporting people. How ridiculous!” Despite my expectations of the notorious law enforcement in this country, I was enlightened by her referring to the whole system as “a business.”

The hijab law, which mandates women to cover their hair, alongside the ban on Instagram, and other gender-specific rules derived from interpretations of the Quran are seemingly strict but often circumvented in practice. They are all “solvable”. By solvable, it means people find ways to bypass the rules: paying fines when caught not wearing hijab, subscribing to a VPN service that was silently approved by the government, and bribing your way out of an inspection. The actual practices do not align with the iron-clad policies and Islamic principles emphasized repeatedly by the administration.

I was disheartened, because here lies an inequality where those with financial privilege could buy their freedom, while others could not even afford small rebellions, let alone the long-term pursuit of human rights.

On Si-o-se-pol in Esfahan, a lively scene unfolded. Young women boldly defied the norm, their hair uncovered, couples smoked shisha, and families gathered to play music and enjoy the night view by the Zayanderud River, the largest river of the Iranian Plateau. The peace of the night is so beautiful, just like in any city in the world. It does not feel like Iran. To say this, I admit to having held a stereotype of Iran largely due to the bombardment of negative media coverage. I was wrong. Maybe, all of us were wrong about this country.

The Iranians I met were eager to dispel the online misconceptions. Their curiosity about my solo travels was tinged with a desire to communicate beyond their borders. “Iran is not dangerous,” they said. “We are very hospitable people.” Indeed, the renowned Persian hospitality was heartfelt and this precious experience will be held in my heart forever.

This was a nation where the tension between an authoritarian regime and the people’s resilience was palpable. The government was invested in and committed to suppressing their people, all while ignoring the obviously surfacing societal and economic problems. The ever-growing inflation was highlighted by paying over 20 million Iranian rials (40 Euros) for a single night’s stay. The contrast was apparent from the Skydeck of Tehran’s Milad Tower. One side of the capital gleamed with vibrant lights while the other languished in darkness.

Yet, there was a sense of anticipation among the people, waiting for a moment of change. A moment of rebellion, they believed, was on the horizon.

Nostalgia for a more open, Western-influenced Iran was prevalent in my conversations. My tour guide lamented the changes: “Before, Iran was very open, very Western. It’s different now.” When I searched through pictures of Iran before the Islamic Revolution in 1979, the level of modernity and Westernization was inconceivable, almost an unrecognizable contrast to the same country today.

Despite government restrictions, I noticed the younger generation’s defiance; they avidly followed global trends and maintained access to foreign social media, subtly resisting the status quo. This undercurrent of resilience and hope was a testament to the Iranian spirit. The people, especially the youth, seemed to long for a return to a past where freedom and openness were the norm, a silent yet profound resistance to their current reality.

My trip concluded abruptly, leaving me surprised at how swiftly the time had passed. While I learned of so many powerful and enlightening stories, I felt powerless and helpless. I was just a tourist, and I couldn’t offer more than my sympathy and mental support, which, honestly, did not appear helpful. My departure from Iran at midnight was vividly recorded in my travel diary. “I doubt I will come back. It felt oppressed,” I wrote. While the bustling bazaars and hustling streets were no doubt captivating, it felt superficial, like an overdone performance masking the reality of a society struggling to maintain its basic foundations.

I saw the hope and resilience of Iranians, regardless of their age, gender, and social background. “I believe one day Iran will change,” said the guesthouse owner, and this was echoed by so many people I met on this trip. I believe so too. Certainly, Iran’s time for change is near, and the hopeful await its transformation.

Other posts that may interest you:

- The Trouble with ‘Ecocide’

- Carbon dioxide removal – hit or miss?

- Local Victories for Turkish Opposition — A Sign of Hope?

- Are France and Japan a Mismatch Made in Heaven?

- A Reflection on Dark Tourism

Discover more from The Sundial Press

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.