Nowruz (also known as Nauryz or Navruz), the Central Asian New Year, stands as a testament to the cultural richness and resilience of the region. Despite not being widely known in the West, it is one of the cultural pillars for the people in the region.

- Historical Origins:

Nowruz, meaning “New Day” in Persian, is embedded within ancient Zoroastrian traditions and marks the beginning of spring and the new year. For reference, Zoroastrianism, one of the world’s oldest monotheistic religions, revered nature and its cycles, and emphasized the eternal struggle between light and darkness, good and evil. Nowruz emerged as a celebration of the vernal equinox (March 21), marking the end of winter and the beginning of spring. The festival symbolized the triumph of light over darkness, fertility over barrenness, and life over death.

The festival is believed to have originated in the ancient Persian Empire, which spanned modern-day Iran, Central Asia, and parts of the Caucasus and Anatolia. Its origins can be traced back over 3,000 years to the pre-Islamic era when Zoroastrianism was the dominant religion in the region.

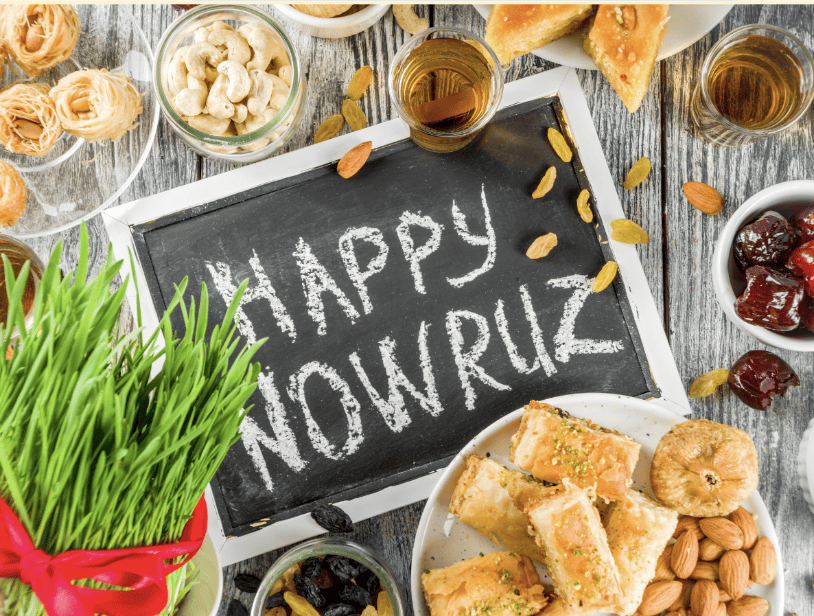

Central to Nowruz is the concept of renewal and rebirth, reflected in various rituals and customs observed during the festival. One of the most iconic traditions is the Haft-Seen table, where seven symbolic items starting with the Persian letter “seen” (س) are displayed, each representing different aspects of life and nature. These items often include sprouted wheat or barley representing rebirth, apples symbolizing beauty and health, and garlic signifying medicine and health.

Another integral part of Nowruz is the practice of spring cleaning, where homes are thoroughly cleaned and decorated to welcome the new year. This tradition symbolizes purification and the casting away of the previous year’s troubles, making way for a fresh start.

- Repression of the Holiday:

Despite its cultural significance, Nowruz faced repression under the various regimes that sought to suppress indigenous traditions and promote state-sanctioned ideologies.

In Central Asia:

During the Soviet era, Nowruz faced significant repression as authorities sought to enforce communist ideology and suppress indigenous cultural traditions. Therefore Nowruz, with its deep-rooted connections to pre-Islamic customs and Zoroastrianism, was viewed with suspicion. Under Soviet rule, celebrations of Nowruz were often discouraged or outright banned, particularly in Central Asian republics such as Uzbekistan, Turkmenistan, Tajikistan, and Kazakhstan.

Participants in Nowruz festivities faced persecution, including arrests, imprisonment, and harassment by Soviet authorities. Religious leaders and traditional practitioners were targeted for their role in organizing and preserving cultural rituals associated with the holiday. The suppression of Nowruz was part of broader efforts to undermine indigenous cultures and assimilate diverse ethnic groups into the Soviet collective, through major migration policies, russification, and erasure of indigenous languages.

Following the collapse of the Soviet Union, many Central Asian states transitioned to authoritarian regimes. Some of them continued to suppress Nowruz and other cultural expressions by deeming them incompatible with state ideology. Leaders in countries like Uzbekistan and Turkmenistan intended to consolidate power and promote a centralized national identity, often at the expense of ethnic and cultural diversity. On the other hand, countries like Tajikistan and Kazakhstan accepted Nowruz as part of their cultural heritage as soon as they gained independence.

Despite repression, Nowruz has persisted as a symbol of cultural resilience and resistance in Central Asia. Communities found ways to clandestinely observe the holiday, often in private homes or rural areas away from the prying eyes of authorities. Underground networks emerged to preserve and transmit traditional customs and rituals associated with Nowruz, ensuring its survival despite official attempts to suppress it. With time, governments increasingly acknowledged Nowruz as an official holiday, granting it legal status and incorporating it into public calendars and official ceremonies.

In Turkey:

In Turkey, Nowruz, known as “Nevruz” or “Newroz,” has always held significant cultural and historical importance, particularly among the Kurdish population and other ethnic minorities in the country. However, the relationship between Nowruz and the Turkish state has been complex, with periods of repression and resurgence.

During various periods in Turkey’s history, especially under authoritarian regimes, the celebration of Nowruz faced repression, viewed as a potential symbol of Kurdish identity and nationalism. Consequently, celebrations were often suppressed, and participants faced harassment and persecution. Under the policies of cultural assimilation pursued by the Turkish state in the past, expressions of Kurdish culture, including Nowruz celebrations, were often marginalized or banned. Authorities sought to promote a homogenized Turkish identity, discouraging the acknowledgment of Kurdish cultural distinctiveness.

Despite repression, Nowruz persisted as a symbol of Kurdish identity and cultural heritage in Turkey. With the gradual democratization of the country and the recognition of cultural diversity, there has been a resurgence of interest in Nowruz celebrations. In recent years, there has been greater tolerance and even official recognition of Nowruz as a cultural event in Turkey. The Turkish government has allowed public celebrations of Nowruz in various cities, with official acknowledgment of its significance as a cultural festival.

Nowruz holds broader significance beyond its cultural and historical roots. For many Kurds, it is not just a celebration of the arrival of spring but also a symbol of resistance, solidarity, and aspirations for cultural and political rights. For several years, Nowruz celebrations in Turkey have occasionally been accompanied by political demonstrations or expressions of Kurdish nationalism, reflecting the ongoing tensions and struggles for recognition and autonomy.

- Recognition of the Holiday and its Status Today:

Even though the history of Nowruz is not bright all the way through, many cultures around the globe help it to thrive. With the advent of independence in Central Asian states, there has been a resurgence of interest in traditional customs and celebrations. Governments have increasingly recognized Nowruz as an official holiday, reflecting a broader shift towards acknowledging and preserving cultural patrimony.

Today, Nowruz is celebrated with renewed enthusiasm across Central Asia, with festivities that include music, dance, food, and family gatherings. Governments have incorporated Nowruz into official calendars and public ceremonies, signaling a departure from past attempts to suppress indigenous traditions. The holiday serves as a unifying force, bringing together diverse communities to celebrate shared cultural heritage and values.

Other posts that may interest you:

- The Trouble with ‘Ecocide’

- Carbon dioxide removal – hit or miss?

- Local Victories for Turkish Opposition — A Sign of Hope?

- Are France and Japan a Mismatch Made in Heaven?

- A Reflection on Dark Tourism

Discover more from The Sundial Press

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.