As Harry Truman once said, “If you want a friend in Washington, get a dog .” Politics have conventionally been known to be a game of distrust. Today, even more so, as polarization has bifurcated politics into camps of respective enmity. Long gone are disagreements on tax policy; instead, resentments seep fervently, crystalizing into something far deeper.

While polarization swarms headlines, deep-cut political loyalties are also affecting our social relationships. One is either in agreement or disagreement; others are either friends or foes. Yet, instead of placating hostilities or shielding ourselves from disagreement, relational preferences may be further widening the divides — we feel acrimony for people who do not share our views. Have political views truly managed to sever our relationships as well? What does this mean for socialization? Is there a productive way out?

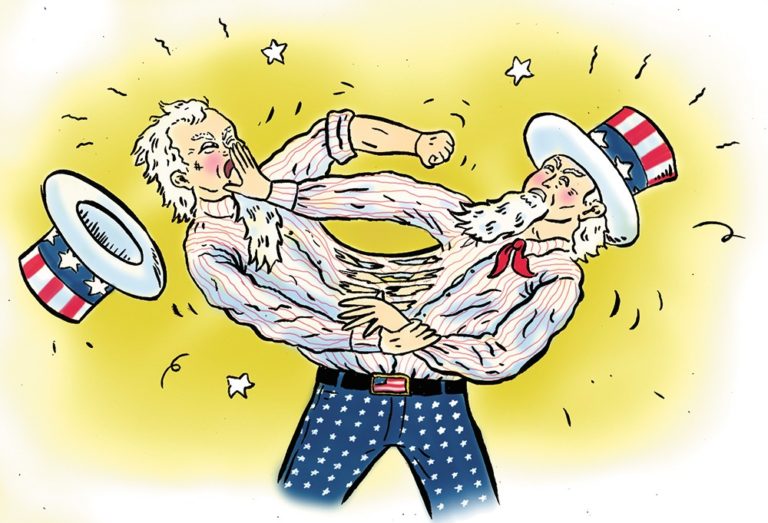

As the saying goes, friendship and politics do not mix. Looking at the US election, one cannot overstate how divisive the political territory has become. Leading up to and following the outcome of the last elections, heated dialogue is in full swing. Thirty years after James Davison Hunter coined the term “culture wars”, the current political landscape has become a battleground where rooting for a political position is now an existential venture.

Both ‘Democratic’ and ‘Republican’ have evolved from political frames of reference into identities themselves. Consequently, as Lilliana Mason points out in her book Uncivil Agreement – How Politics Became Our Identity, “More often than not, citizens do not choose which party to support based on policy opinion; they alter their policy opinion according to which party they support.” Extremism continues to prompt partisan polarization as well as affective polarization – a landscape in which both camps consider other party members as closed-minded, selfish and hostile. As many as 72 % of Republicans and 64 % of Democrats see members of the other party as more dishonest than other Americans. Taking the temperature of public discourse confirms the diagnosis of division. Take, for example, radio host Sid Rosberg’s recent description of the Democratic party as “a bunch of degenerates”. Biden and Clinton have both faced outcry for their labelling of Republicans as “Neanderthal” and “deplorables”, adding fuel to already inflamed political divisions.

According to Professor Tania Israel, opposing sides now “tend to view the other as being more extreme than they are.” Since 1978, negative sentiments against the rival party have climbed at a pace of 4.8 points per decade. Dialogue has become both derogatory and unconstructive, polarising the other and flattening out people into enemies.

This reciprocal ostracism has caused people to avoid socializing beyond party boundaries. For instance, longitudinal survey data showcased a 35% increase in American parents who would be unhappy with their child marrying someone from the opposite party. Similar patterns were made evident in the online dating community, where “matching” is more common with those sharing similar political beliefs. A 2020 survey by the Pew Research Center revealed that four out of ten registered voters did not have any close friends who supported the counterparty.

The wall is heightened in echo chambers. Social networks often see no moderation, and opening any comment section makes it clear: derogatory references and aggressive rhetoric are becoming normal. In a collaboration between Princeton University and Arizona State University, researchers demonstrated how social media not only reflects but also contributes to social sorting. Almost unintentionally, through preferential affinity, users generate self-curated feeds by unfollowing accounts seen as untrustworthy. As such, link suggestion algorithms react accordingly, fostering social reinforcement and intensifying radicalisation on social media. Conversely, “people who are part of a network consisting of a variety of viewpoints tend to moderate one another”. The unintentional construction of echo chambers contributes to political dialogue that remains incapable of formulating a variety of solutions necessary to depart from socio-political stasis.

Psychological tendencies hold a lever here too. Termed as the similar-to-me effect, there is a human tendency to seek interactions with people like ourselves, as it helps to reinforce our identity. Additionally, friendship is in itself a mental mapping system – a heuristic which contributes to validating our sense of self. Yet, this human predisposition in choosing relationships has become a well-oiled cog in the “two-part engine of polarization”. Political homophily further enhances social rifts. When political preferences precede social assimilation, we become limited to sameness and entrenched in unproductive animosity.

So, should one not mix friendship and politics? While it has always been dinner table talk, should the solution in such culturally divided times be to avoid disagreement completely? Should we disengage and remain soiled in the comfort of sameness?

Todd B. Kashdan Ph.D. warns against this contingency of friendships based on political allegiances. Viewing friendship through ideological purity reduces the quality of human connections. Engaging more and diversifying friendships has shown to be empirically more productive. Indeed, taking the US once more as an example, Democrats and Republicans with outparty friends felt less social distance. Judy Hom, clinical and forensic neuropsychologist and Professor of Psychology at Pepperdine University, instead advises on active listening, stepping away from prejudice, and not “mentally preparing rebuttal” when interacting with the other side.

Seeking out only those “like us” cages us in a bubble of relational confirmation bias, allowing us to gain confidence in our exclusive righteousness. Counterintuitively, as we seek to protect ourselves from dissimilar views, we ramp up extremism. This does not mean remaining neutral or abandoning opinions but rather moving away from the idea of vanquishment, which serves as an obstacle to cooperative problem-solving. By not engaging productively with one another, we encourage lingering bitterness.

Avoidance unconsciously fields divides that are unproductive and unwittingly feed into the narratives of figureheads. Toning down our rhetoric and not mistaking political preferences for out-group isolation seems like a necessary first step toward de-escalation. Suppose our core interactions steered towards a more open moderation. In that case, we may recenter the political compass from its current problem-creating dimension to its original function as a problem-solving space, thriving on productive coexistence.

Cover : Doug Dickerson (dougdickerson.net)

Other posts that may interest you:

Discover more from The Sundial Press

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.