Credit: Holly Warburton for the New Yorker

As he crouched in the field with the sun beating down on his back, he began to realize the profoundly bothersome way the strap of his harvesting basket dug into the flesh of his shoulder. It was late July, and most of the beginning of summer was spent cultivating the tea leaves to prepare for mid-summer’s peak harvest, pruning and clipping the bushes to make room for new growth. He had never been particularly fond of tea, though his mother brewed it constantly. Yet at the beginning of harvesting season, before he would become disillusioned and ached at the sight of a tea leaf, the smell of it all would draw deep breaths in his diaphragm as his heart slowed down to a leisurely rhythm.

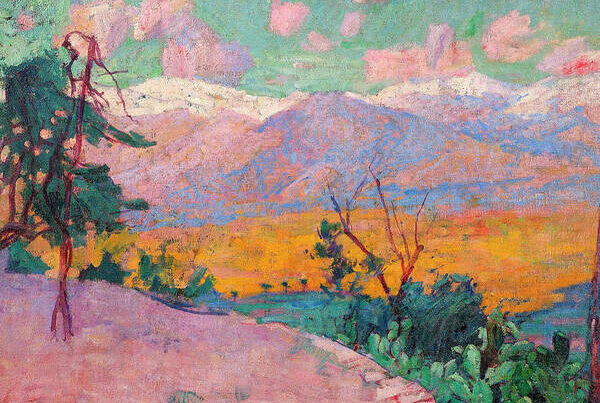

Early morning, the laterite soil was moist with overnight precipitation, and the humidity hung low in the air, bathing everything in a gray dewy cover, save for a few pockets of cloud where the sun would sneak through and illuminate a patch of crop. At those certain parts, the freshest budding leaves of the tea plant would be lightly warmed with the rays of sunlight, and produce a faintly aromatic redolence only identified by one resolute to distinguish the scent beneath layers of rotting compost and the musk of drying sweat on tanning skin.

But if he spent a morning solely tending to the plants, he could not only identify the smell of the warming leaves, but relish in it, and for such brief moments between hard bromidic and tedious work, he was in love with the world and all it could produce. And even sometimes as July faded into August, and the days grew longer with work, he would find pockets of time within the day, under the overreaching shadow of a rubber tree, to trace the spots in the dirt where stones turned over and dried remnants of leaves lay stagnant beneath the loam. He would plant his back onto the trunk of the trees, feigning acupuncture treatments after supine afternoon naps with the imprint of the tree bark’s pattern leaving fresh pink marks on his tensed lateral muscles and the perpetual hunch of his spine. He could discover nests left over by some migratory bird, cobwebs drooping between branches, the rough shells of nuts weathered by rain and cracked underfoot.

He found moments of solace under the watchful eye of his father, unaffected by the same conditions others drew their motivation for work from, free from insecurities of hunger or shelter or thirst, because despite the continuous work he was put under during the waxing and waning of harvesting seasons, he knew his punishment for sloth would never amount to exile from the household. And so he took advantage of the flexibility in his working hours and lounging hours, taking particular emphasis on the latter, his mind empty and soundless against the whirr of cicadas and the turn of the tea roaster, a motionless hour waxing and waning with the gentle bend of branches. Though after Etan, he harbored a sinking resentment for the doubling of quotas and work to be fulfilled, he rarely completed his harvesting on time, his work sloppy with leaves left on bushes and weight quotas unreached. As four hands fell to one, and idle chat resounded silent, there was a visible emptiness in the fields, certain harvesting baskets left untouched, handles worn through from rough calluses left to erode under rain. He was pushed enough to complete his work and fill enough for drying, roasting, and packaging, but never again enough to the point of Etan, to the exhaustive monotony of pulsating nausea from summers before.

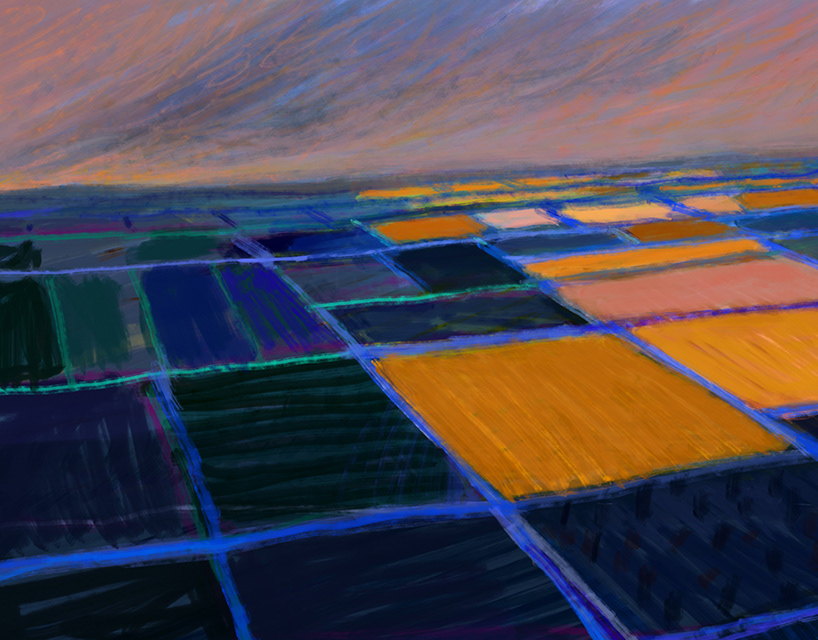

Things were slower now. Production rates dropped, shipment became exclusive, the blue doored truck, that bi-weekly stopped to a screech outside the house’s bamboo porches to bring towards the city bundles of roasted tea, now rolled onto clay roads once a month at maximum. The vivid picture he frequented coming back from the fields of his mother seated in front of the short wooden table in the kitchen, funneling roasted leaves through old newspapers into squat metal containers one by one, faded into seasonal appearances. The rest of the house boasted a stale creak of doors left unopened and belongings left untouched. Rooms emanated with budding whispers and ghosts of midnight conversations. Even jackrabbits and insects dulled to a gentle settlement, as if they, too, had grown accustomed to the quiet.

Alone, he remained on the harvesting plains, feet heavy into the uneven dirt and undergrowth, thumb and index finger stained green and brown with oxidizing leaf remnants. The sun continued to beat, the basket continued to dig into his shoulders, and the leaves left unharvested glared sanctimoniously in their elevated perches.

Perhaps the world would move on without him, shipments slowing and fields left to grow wild, but he knew that within the softness of the soil and the creak of the house, there was something that still held him. It was folded into the land, into the rows of tea bushes and the soil beneath his feet, into the indentations in mud and soul. He would always be rooted here, in the tea fields, where time moved slowly, and the weight of the lost became something he could finally bear.

Other posts that may interest you:

Discover more from The Sundial Press

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.