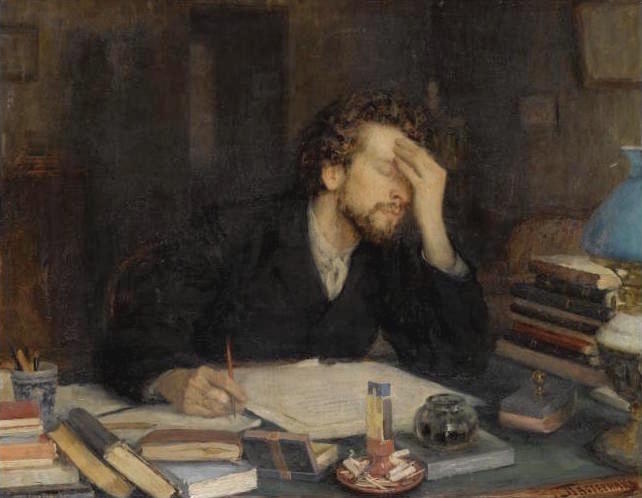

Credit: The Passion of Creation – Leonid Pasternak

A short introduction

The University is cruel in its ways to keep the public unaware of what happens in its hallowed halls. Hushed whispers glide along the large stone walls, confined in the momentum of the conversation, only to be locked away in the minds of those speaking. It was not always like this. In the beginning, when the University was founded, scholars had a hard time containing the excitement over their academic work, although they were always careful to keep it secret to those not worthy of being privy to knowledge’s allure. However, if there is one thing this place loves more than heavy, hardback tomes, it is intrigue, mystery, a good story that plagues your days and nights for decades before it finally settles as an imminent part of your subconscious.

Some of the stories are harmless fun, conjured up after a particularly exciting night at one of the nearby taverns. Where alcohol flows, minds wander in the depths of their imagination to create a story worthy of decade-long appreciation.

One such story is the legend behind the creation of Narnia. Supposedly, during one drunken night back in 1918, C.S. Lewis came up with the idea of the imaginary land, while staring at a lamp.

One of the favourite tales of any professor over the acceptable age of retirement is about a group of students, who frequented a certain tavern close to All Souls College. They were a rowdy bunch of men, who harassed the owner’s daughter and, naturally, were expelled. Then they decided to create Cambridge.

However, dear reader, I do not wish for you to get the wrong idea. The more you listen to the cold gusts of wind in the old Bodleian library and the quiet murmuring of the librarians, the more you will understand the consequences of letting your guard down in a place like this. Soon enough, you will begin to comprehend, try as you might not to, that there are far more sinister and dangerous things on the grounds of this University than the law exam at the end of the Hilary term.

The Sheldonian theatre incidents have always been reported to be an ire try of the newly graduated students to frighten everyone else. A simple jest, one last amusement before leaving the cobbled streets of the city. After all, nobody could ever confirm nor deny that they were, indeed, lying about what they saw. However, I would strongly advise against any inclination to believe their words are anything but a warning.

Graduation at Oxford follows the same tried routine that it has for the past exorbitant number of decades. The Divinity School is not of particular splendour nor size, yet it is just as beautiful and ornate as any other university building. It boasts a hand-decorated ceiling and walls, which took some 60 years to make during the War of the Roses. In this very building, you put on the old gown, always smelling of sweat, which has been passed down from generation to generation. Afterwards, you enter the Sheldonian theatre where the actual ceremony begins. It is a tedious affair, however you should most definitely count your blessings if all you have to worry about is mind-numbing boredom.

They come without any warning, swarming the dome of the theatre with their long, black wings and foul smell. The creatures are hard to describe, as the memory of them fades just as quickly as they appear. Nonetheless, I will try to the best of my ability to relay the events to the extent of which I remember them.

It was a particularly cold June day in 1928. Angry clouds gathered above our heads as we made our way into the Divinity School. The gown they had given me was dusty and smelled of rotten wood. It was made from a thick, rough fabric, which scratched my neck with every move, so I resigned myself to looking straight ahead. Suddenly, two slender hands around my waist sent an electric current through my body. Memories of a violent storm in the middle of the night and the unclenched jaw of a transparent ghost flashed in my mind. I jumped two steps ahead in fear, yet when I turned around all I saw was the warm smile of my friend Elisabeth —– the only summa cum laude in our class of 1928, Bachelor’s of English Literature and Poetry. Despite the horrendous clothes from the university, she still managed to look put together with her long blond hair and crystal-clear complexion. Her cheeks creased where her dimples created shallow hollows in her face.

“All these years and you still jump like a deer in front of headlights.” She giggled warmly and covered her mouth with her hand.

I looked at her incredulously and sighed. “Well, we both know I’ve always found your jests far more stress-inducing than whatever this place has ever thrown in our faces.”

“Luckily enough, after today we no longer have to see these buildings for the rest of our lives. Unless you make a promise out of your threats to return here and become the greatest academic the world has ever seen.”

Oh, dearest Elisabeth, if only you knew.

Apart from the electric excitement to continue with a new chapter of my life, I was also deeply saddened by the idea of leaving the university, despite all the harrowing events of the previous years. From our very arrival in the city, we were thrust into the mysteries of the supernatural: loud screams in the middle of the night, a foreign reflection in the mirror of the dorm’s bathroom, the creak of the floorboards in the corridors made by an invisible entity. Yet, Elisabeth and I took it all in stride and sometimes, even to this day, I owe my well-being to her existence. Her presence always somehow soothed the calamities, which followed our backs.

“That entirely depends on whether the dean is nice to me when he hands me my diploma,” I joked and saw the stream of our fellows walk out of the school. “Let us go, Lizzie.”

For what I thought would be the last time seeing the dome of the Sheldonian, I straightened my back and followed my friend into the building.

It was a grand old thing made from deep mahogany and heavy, white stone. A series of windows circulated the building, but despite their size and quantity, the inside of the theatre was uncharacteristically dark and cold. A half-circle of wooden benches spread before us. One by one, we all took our respective seats in front of the podium where the deans and the professors would make their speeches.

Despite any attempts by the upperclassmen to frighten you with rumours of screaming ghouls during the ceremony, do not listen to them, as what you will witness will be far worse. There will not be any screaming involved, just cold, unfiltered fear running through your veins as a large shadow above your head will engulf the insides of the theatre. The smell will always be the first thing your sensory nerves process.

The stench of a decomposed carcass filled my nostrils and I turned to my side where Elisabeth was sitting. We exchanged a fearful look, before slowly weaving our hands together and calmly looking up. Their elongated scaly bodies encompassed the entire dome, casting long shadows on us. The speeches continued as they were and the remainder of the student body kept entirely still in their seats, for nobody knew what would come if they did move. Suddenly, one of the foreign beings landed their long-toed feet on the end of our wooden bench. A loud clamour upon the landing echoed in the theatre. I tightened my grip on Elisabeth’s hand and silently prayed that would be the end of it. However, when I turned to catch her gaze again, her eyes weren’t on me, instead she was frozen in her seat, staring into the large bright eyes of the lizard-like creature. My foot instinctively slammed into hers to get her out of the trance she was under, but it was already too late. The wyvern extended its black neck and in a swift motion bit off her upper body.

Blood sprayed on me like a cold shower and the presence of her hand in mine was occupied by the limpness of whatever was left of her. I disassociated, a storm cloud of numbness hindering my ability to think.

The continuity of events is reliant on the accounts of everyone else, who was present at the time, for I do not remember anything afterwards. The speeches had stopped at that moment until the wyverns gathered at the top of the dome and then disappeared without another casualty taking place. Supposedly, the graduation was postponed for the next week and the diploma on my wall is a testament to that, yet I have no recollection of such an event. The entire extent of the version of events the administration described to Elisabeth’s parents is unknown to me, but as far as I am aware, she is considered missing, after having run away. For all they knew, she could’ve taken a boat to France and forged a new identity for peculiar reasons. Whatever imaginary tale they were fed, it was better than what had truly transpired.

My return to Oxford the next year was all the more surprising, yet I could not help but feel responsible for those who came after me. I would like to believe Elisabeth would want to be remembered as a reason for other lives to be saved.

The wyverns in the Sheldonian (see Chapter 7) are one of the many peculiarities of this place, but by far not one of the worst, as surprising as it may sound. The ghouls’ howling every full moon in the court of Christ Church college (see Chapter 8) is said to be far more heart palpitation-inducing than whatever else you are going to witness during your years at Oxford. Yet, I cannot help but disagree. The road to hell is paved with bones sticking out from grassy patches, wide white eyes staring at you in the dark as you try to sleep, and the faint smell of chlorine in all drinkable water.

Dear reader, I do not mean to scare you, for the shadows only grow as large as your fear will let them. I simply hope to prepare you for what is to come. Should you find this piece of writing, do not, under any circumstance, put it back where you found it, or they will find you. Find someplace else —– a hole in a secret courtyard, a stack of books that belongs to your professor, the floorboards of your neighbour’s dorm. One thing you should never do, however, is fully get rid of it. Do not even think of burning it, cutting it into a million different pieces, chucking it into a mass of water far, far away from the limits of this city. Even I cannot fathom the consequences of such carelessness.

Dear reader, tread carefully with the knowledge of this book. And remember, none of this is true.

Dominus illuminatio mea.

A. Dankworth, 1932

Other posts that may interest you:

Discover more from The Sundial Press

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.