Credit: Netflix

Is it a comedy? A horror film? Perhaps neither, and yet both—a psychological thriller. In “Get Out”, through the duality of this genre, Jordan Peele unpacks the complex nature of race relations while tackling popular social and cultural issues. Most notably, the underlying relationship between systemic racism and white liberals.

Tucked in bed with two fluffy duvets, check. Rain outside, check. Box of Sucré cookies, check. My roommate and I were ready for our traditional Friday night movie.

Expecting and having mentally prepared to watch horror, the bloody graphics, grotesque images and repugnant motion pictures were lacking, to our surprise. But we were left unsettled, unnerved, at a loss for words, and with an excess of thoughts. Why was it not the blood, the hit-and-run or the gunshot scenes that had elicited the most fear? Instead, why was it the hypnosis that evoked the greatest ensemble of shock and disgust? Peele skillfully taps into a more cerebral source of tension through the exploration of a psychologically dark matter. He presents the raw, yet dramatized reality of US citizens trying to navigate a rough racial dynamic, where the white perspective lionizes and demonizes black people, dictating their perception of their own identity.

“Get Out” narrates the story of twenty-six-year-old Chris Washington, a black photographer, who travels to upstate New York for a weekend getaway to meet the family of his white girlfriend, Rose Armitage. However, we slowly realize that the family’s attempted friendliness is merely a facade hiding a twisted plan.

Through dialogue with the Armitages, enriched by symbolism and parallelism, Peele portrays the family’s romanticization of blackness as an object for white people to possess—ironically, by those who claim to “have moved beyond racism.”

“Get Out” must be seen as a critique of white liberals “who are trying to understand black culture” but are hindered by their ignorance, preventing them from humanizing the experience. Peele initially showcases this phenomenon through the interaction between Chris and Rose’s family, thereby setting the tone of the movie.

Rose’s father attempts to mask his discomfort with exaggerated friendliness by repeatedly using the stereotypical “my man” slang. He is quick in telling him that he would have voted for “Obama a third time” if he could, letting him know he was “the best president ever.” This overenthusiastic display of acceptance paints the family as awkwardly out of touch, and “racially clumsy”, cementing a distance between Chris and the Armitages.

These conversations are laced with passive-aggressive and racially charged undertones. Rose’s brother, Jeremy, is quick to point out Chris’s “primitive instincts” as he suggests that “his frame and genetic makeup” could transform him into a “beast.” Peele’s script reveals a deeper layer of covert racism beneath their surface-level politeness. “Bro, this is like the casual racism in like half the US states,” mumbled my friend, whilst simultaneously taking her last sips of strawberry milk.

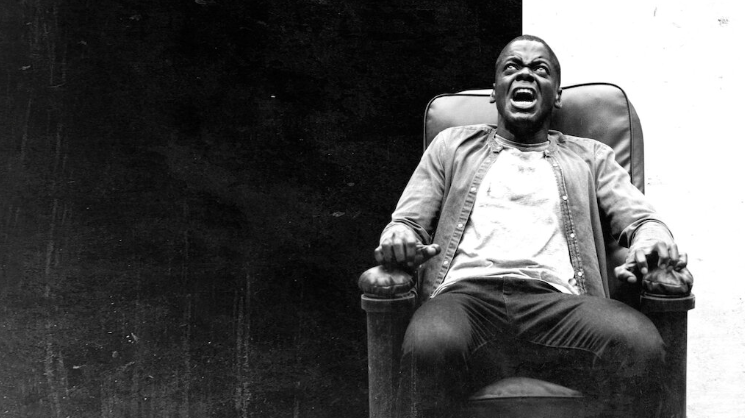

The narrative later follows Chris as he slowly realizes that he is the next victim of the Armitages’ twisted plan, in which the brains of wealthy white people are transplanted into others’ bodies to grant them desired physical traits. However, by the time he awakens strapped to an armchair in the basement, it is already too late.

Chris’ liberation is nothing short of symbolic, or as described upon viewing that night, “low-key iconic.” As the dark underpinnings of the family’s motives slowly unravel, Chris repurposes everyday items, imbuing them with new meaning and using them as tools for his survival. These once-innocent objects become his weapons of freedom. One particularly poignant scene, now referred to by fans as the “cotton-picking moment,” sees Chris stuffing cotton buds into his ears to block the hypnotic control exerted over him. The act is a haunting reminder of the forced labor endured by slaves in the past, turning a symbol of historical oppression into an instrument of resistance. In another moment of bitter irony, he uses bocce balls, symbols of leisure and privilege, to fight for liberation. These items are transformed into instruments of survival, showing how Chris must weaponize the very symbols of his subjugation. The denouement had us standing on our beds screaming “Run, Chris, Run!”

The film ends. We are acutely aware that both of us are still awake. The computer is shut down, the lights switched off. Yet we remain awake.

“It’s scary how realistic this horror movie is,” I whisper.

“There is more truth than fiction in Get Out,” my roommate answers.

Other posts that may interest you:

Discover more from The Sundial Press

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.