This article is part of our series in collaboration with International Policy Review at IE University. You can read more articles at the link just above.

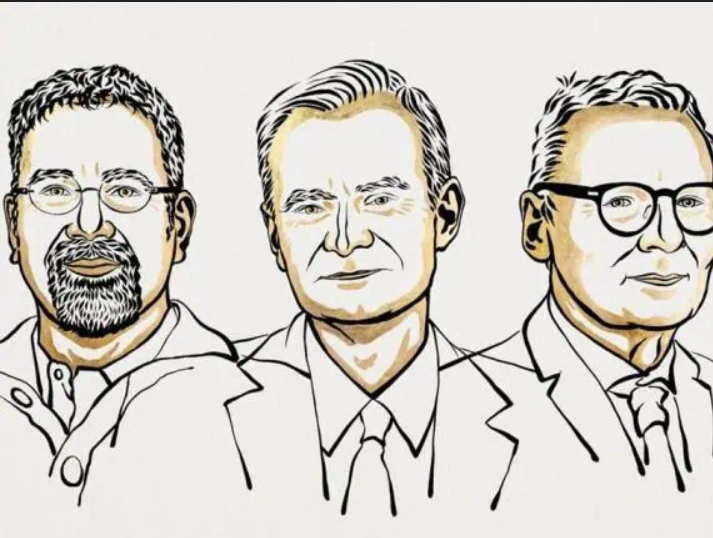

Image Credit: The Nobel Prize

By Isabela Bortolotto Rodacki. Edited by Nelly Lou-Anne Pedrono.

The Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences decided to award Daron Acemoglu, Simon Johnson, and James Robinson the Sveriges Riksbank Prize in Economic Sciences in Memory of Alfred Nobel 2024. In the econ community, it was very much expected that the trio of economists, known as AJR, were going to win a Nobel for their work on how good societal institutions shape economic prosperity. The paper covering the basis of their research, “The Colonial Origins of Comparative Development: an Empirical Investigation“, is one of the most cited in economics, and Acemoglu and Robinson’s 2012 book “Why Nations Fail” is also extremely significant.

When trying to answer the question of the century on why some countries are poor and others rich, “Why Nations Fail” is a comprehensive study on the establishment of societal institutions, dividing them into “inclusive” or “extractive”.

In settler colonies, like the US or Australia, Europeans established inclusive institutions that foster property rights, the rule of law, and democracy. Whereas, in non-settler colonies, like most African ones, extractive institutions persisted resulting in a high concentration of power in small elites, with little benefits for the overall population. According to AJR, a country will prosper if their societal institutions are inclusive.

Although there is no doubt that these economists made significant findings, the decision to award them a Nobel Prize is quite controversial. While the discussion of colonialism is a pillar in AJR’s research, they fall into the common trap of Eurocentrism. The trio’s conception of “good” institutions is deeply rooted in Western concepts of development. And claiming that the liberal European model is the way to achieve economic prosperity could be perceived as an outdated Fukuyaman view of the world.

Yuen Yuen Ang, a Singaporean researcher on Chinese development, posted on X that “I don’t agree with their idealised portrayal of institutions in Western development. It is historically inaccurate, if not ideologized”. The criticisms on AJR’s work follows Yuen Yuen Ang’s view, with scholars highlighting the existence of examples that contradict their notion of prosperity without “inclusive institutions”. This includes China, which the authors struggle to explain in Why Nations Fail, and Singapore that seemed to develop just fine before democratisation.

Also on X, the former Chief Economic Advisor to the Government of India, Arvind Subramanian, highlights another possible inaccuracy: “their strategy of teasing causation out of the natural experiment of colonisation is debatable because it cannot distinguish between the places that colonisers went to and the human capital they brought along with them”. In settler colonies, in addition to establishing societal institutions based on the liberal European model, Europeans also established themselves. This made it easier for settler colonies to secure trading relationships with already wealthy European countries and provided significant knowledge on how to efficiently operate those institutions, which is clearly pivotal for economic prosperity.

Similarly, disregarding normative concerns, the economists fail to highlight the cruel face of colonialism when discussing economic development. Instead, as Dr. Acemoglu stated after receiving the prize: “Rather than asking whether colonialism is good or bad, we note that different colonial strategies have led to different institutional patterns that have persisted over time,”.

Nonetheless, it is important to recognize how Western inclusive institutions are not inherently good, and the main criticisms pointed out their lack of emphasis on the violent aspect of colonialism. The exploitation of the so-called extractive colonies fostered European wealth and strengthened their institutions. The glorious USA that we know today was built with the hard labour of enslaved Africans, while brutal colonialism in African countries destroyed the possibility of building up strong institutions.

Overall, this emerging criticism demonstrates that people are noticing the Eurocentric bias in internationally recognized studies. It is not surprising that The Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences would endorse research that reaffirms the Western model or that, at least, does not question it. While colonialism is discussed in a non-normative approach, Acemoglu claims that “broadly speaking, the work that we have done favours democracy”. The fact that a piece that reinforces the strength of liberal institutions is awarded a Nobel in 2024 is symbolic of how the Western liberal democratic model is not as unchallenged as Fukuyama claimed it to be at the end of the Cold War. In a world with a powerful China, the ongoing Russia-Ukraine war, and extremely high tensions in the Middle East, the West is still trying hard to maintain its hegemony.

Although Daron Acemoglu, Simon Johnson and James Robinson deserve recognition for their work, the 2024 Nobel Prize in Economics fits into the ongoing Western effort to maintain global influence. In this case, however, there is an increasing awareness within the international community of any underlying motivations.

Other posts that may interest you:

Discover more from The Sundial Press

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.