This article is part of our collaboration with International Policy Review at IE University. Read more in the series at the link just above.

By Logan Pierson-Flagg. Edited by Nelly Lou-Anne Pedrono.

What if your next meal was at the center of a global power struggle? As nations race to secure food and water in an increasingly resource-scarce world, the way we eat today could shape the future of our planet.

Ever since the Industrial Revolution, oil and coal has replaced agriculture at the centre of global economies, with water and food becoming just another commodity being bought and sold in markets. Particularly in the West, consumers of food products are so far removed from the production process that food being readily available in the grocery store is taken for granted. However, the world must not forget that food is power, and the control of global food and water supplies will only become more crucial in an uncertain, climate-impacted future.

This may seem like an issue for future generations, but the reality is that we have already witnessed the destabilising effects of water and food insecurity in Yemen and Syria. While the civil wars in Yemen and Syria cannot be attributed to a single factor, secret U.S. communications from both of these countries’ embassies highlight how water shortages, and the ensuing drop in agricultural production led to a lack of trust in the central government, allowing rebel groups to thrive. However, under these unstable conditions water access and agricultural production have only gotten worse resulting in a downward spiral with no easy solution.

Though it may be tempting to write this off as an issue limited to the desert filled Middle Eastern countries, the largest food production company in Europe, Nestle, believes the dwindling supply of fresh water is the “achilles heal of global agricultural development”. Their chief economist has estimated that if the rest of the world had eaten meat at the same rate as the United States, the world would have run out of water in 2000. Given countries like India and China are rapidly developing, their citizens are demanding more meat-intensive diets, putting further pressure on water supplies.

Governments across the world have already begun reacting to these developments with countries like China and Saudi Arabia making moves to ensure their populations have access to food no matter the global situation. Saudi Arabia has been the most aggressive with its policies since it has already depleted its own water sources. In the 1980s Saudi Arabia pursued an aggressive agricultural policy resulting in it becoming the sixth largest producer of wheat in the world despite the fact that its land consists mostly of desert.

However, this came at a great cost as they completely emptied their underground water sources in only thirty years, even though they are as old as the Bible. With 70% of its water today coming from desalination plants, it can no longer sustain these levels of production within its own borders. However, this has not stopped the government from ensuring its own citizens will continue to have food security in the future. In order to achieve this, they have shifted their production of wheat to Arizona where there are no restrictions on pumping out groundwater. They then ship the wheat grown in Arizona back to Saudi Arabia in order to feed mainly cattle, something experts refer to as exporting virtual water.

Saudi Arabia is not the only government today preparing for a future where access to food and water would not only be a problem for the developing world, but for the entire planet. In the last 50 years China has experienced one of the greatest reductions in poverty ever seen, with hundreds of millions of people entering the middle class.

However, this has also resulted in a changing diet and culture around food with demand for meat greatly increasing. In order to ensure the supply of food can keep up with this growing demand, the Chinese government began quietly encouraging its private companies to buy large international food companies. This policy can be most clearly seen in the Shuanghui takeover of Smithfield, the largest pork producer in the United States, in 2013. This purchase has resulted in a Chinese company owning one in four pigs in the United States.

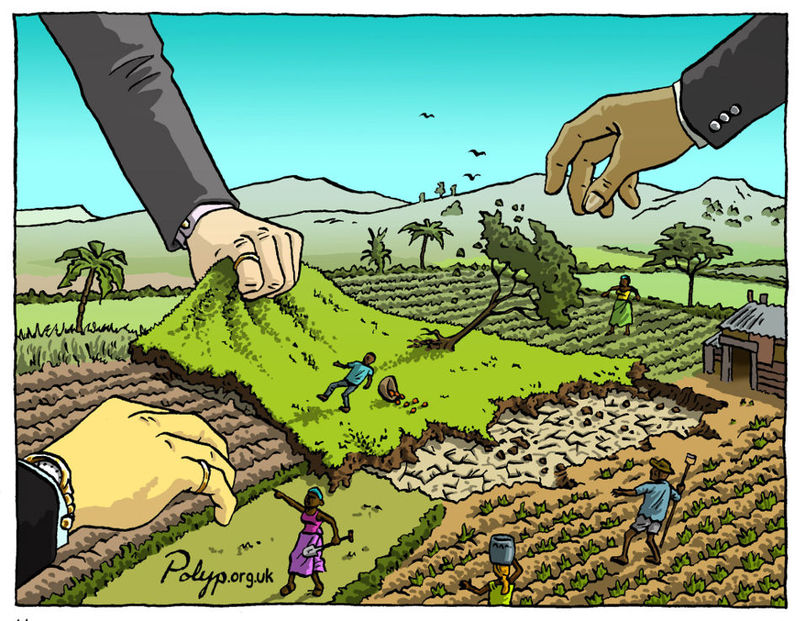

This policy is not restricted to the United States as other Chinese companies have also been buying increasingly large amounts of land in the developing world where locals have few means of resistance. This practice is not limited to authoritarian governments, with India and South Korea also joining the land rush for African agricultural land.

It is hard to blame countries for taking steps to ensure their citizens have access to food in an increasingly uncertain future. The interconnection between conflict and food is already being seen today with food being weaponized in Sudan and Gaza. According to a recent UN report, “the number of people experiencing catastrophic hunger has surged more than twofold in 2024”. Conflict has been the main driver of this increase, with the wars in Gaza and Sudan exposing millions to famine. While hunger is not a new phenomenon of war, its use as a means of asserting power is something the new international order is meant to prevent.

Global cooperation on food security is the only way to ensure that the world does not enter a Hobbesian state of nature where one must fight to secure barely enough for one’s own survival. While access to oil has driven wars and destabilised countries across the world, food as a source of conflict poses a uniquely terrifying threat. When people do not have access to food and water and have no ability to produce their own, they use desperate means. This facilitates the use of food as a method for dividing societies and maintaining power for corrupt and selfish leaders who do not care about their people’s well-being. For example, studies in Somalia have shown the relationship between food insecurity and increased levels of conflict. As precipitation levels decreased in the 1990s and 2000s, the number of terrorist attacks also hit record levels. Many fighters attributed their joining of terrorist organisations to socioeconomic conditions rather than any ideological sentiment highlighting the direct link between food scarcity and violence.

In a world where technology and those who own it promise to solve many of the world’s problems with AI, society must not forget the centrality of food systems to our civilization. Countries across the global north, from China and Saudi Arabia to Japan and India recognize this and have begun trading technology and infrastructure with the promise of economic development to countries across the world in exchange for access to land and the crops grown there. However, what these countries must understand is that food security is not a zero sum game that one country can win, but must be tackled globally. In times of scarcity and desperation people will not accept food grown on their land being shipped thousands of miles away while their family starves. While these policies may give these governments more short and medium term stability, the reality is in the long-term it is not sustainable.

This is why the only path forward is through cooperation that ensures every country can maximise its own production while ensuring efficient distribution around the world. This need has been recognized by countries including Norway, Sierra Leone, Rwanda, Cambodia and Brazil who have established the Alliance of Champions for Food Systems Transformation. This organization was launched during COP 28 with the goal of transforming our food systems to address their contributions to climate change while also ensuring food security into the future. With hundreds of billions of dollars already being spent on agricultural subsidies every year, countries already have the resources to reconstruct our food system to be more sustainable and future-proof.

This change must begin with our own individual relationship with food. We can no longer see it as just another commodity, but must understand and respect its power to build and tie together or destroy and tear apart the communities underpinning our societies.

Other posts that may interest you:

Discover more from The Sundial Press

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.