A Guest Submission from Sámuel Vető.

You can read our exclusive interview with the author here.

If there is any significance this small narration from a writer of an otherwise humongous prowess, Eva Janikovszky, carries, it is that of the moral that growing up is the hardest thing there is. In spite of how commonly we tend to ponder on what this may or may not carry in its presence, and moreover how possibly apt we consider ourselves to be in answering it (oftentimes too hurriedly and instinctively to properly give our thinking the privilege that is due), we surreptitiously get lost in the implications which we are always locating in a vaguely defined end. In asking ourselves what this strange transformation suggests, we fail to reflect on its evolutionary proportions, which is why we instead conclude where the entire activity – by necessity, but always with an uncertain pretense – concludes, without deeming the development of its object necessary.

At times we are also amiss of the object of our questions. Who or what are we aiming them at? Are we doing so in order to prove something? Is it done in the favor, or for the good of a certain someone? Some very prevalent signs already known to us would say that our perceptions align on the problem of youth.

“Youth”, as a concept, is given to us once a sign of vitality in a person marks that which happens to be present in his age, mood and body, as an expression of life. We see the wild punk, the rowdy city-goer, the chain-smoking teenager, the self-incongruent tween, the nascently attractive girl, the libertine couples as inscribed on the same word: youth entails that its subject diverges, turns things over, disrupts, doing so out of no apparent purpose that would portray an end. Indeed, the beauteous, spectacular and violent dispositions which we have seen being proliferated under this word carries over its meaning into a space where no systematicity appears in how they live: there need be none, because its meaning is to swerve. No mention of purpose here is needed too, because no actual requirement attaches itself to such profusely aesthetic variations.

With respect to this youth, that, recurrently, is life, we sometimes have the impression, as we grow older, to command some regulative arrangements into how these people exist. We see, to borrow two terms from Bergson, a geometric order being warranted rather than a vital order – the preference for propriety, routine and stability ranks over that of flexibility, of ordinary speech, of ambiguity for example, for we see less in something we think of as “disorder” than what we otherwise would think as being “order” proper. In effect, the specific manner with which this strange life lives itself is misread as a notion that is falsely posited to be the line between two fixed dots.

Thus, for so many people to talk of growing up means to pose the inevitable questions to those who are other than them in disposition which are too big for their own (and even their) size: What will you do? When will you stop? When will you act? When will you think? When will you finally start growing up? The subtle expectation of a finish, of an uncoupling, of a sign of termination precedes our concern, and makes of our time-to-time ironic query a reproach that is rendered in the negative. To use that formidable expression that we indeed use when we detect a nuisance in those lives, we take up our words polemically: we are there to vanquish that nasty apparition of an attitude.

We would like to pose to the other person a quality as an example – though many times such is only allusory, having a bearing of no consequence on his actual progression in life – which he, out of no circumstance that would form the matter of our concern, could or would not possess. Such takes form precisely because he is not in that position of holding onto that quality at that moment, regardless whether our intention is that of elevating, encouraging, empowering that who is other than us, even if we may do so only through our own talk of a seen absence.

Following suit, we like to make of our statements abrogations of the now by our expectations of things to come, regardless of affect. We draft up their entire life in front of them. We would like them to follow a plan. Have them stick to routine. Once our intentions reflect such, we have managed to do so perfectly obliviously to, and without any needed account of, what exactly the one we have addressed has to embody. We demand of them a change of an absolutely first degree. Change their looks, their manners, their tastes, their humour – better yet, let’s change their thinking entirely, just let’s not have them be them!

Let’s stay with this image for a moment. When we mention something akin to our desire to change something by giving it a foundation, we like to envision to ourselves the figure of that person who we see as a root of the concern. We see his outlines, his behaviour, we know his faults, and, because we think ourselves to have a clear view of the situation, the truth—as we may as well presume—is on our side. How sure can we be in our own truth once we are called to reflect on our inner life? If we take our own standing consciously of what we are exposed to and conscientiously of what we are receiving, a change of heart would be what we find.

We see life as being presented as a mechanistic pre-arrangement of all the factors we are obligated to abide by, emptied out of all the nothing of what they might be reasoning with compared to the fullness of that which we would take, our talk of purpose does indeed reflect nothing beyond that. If our thinking, the thinking of us, older, experienced, mature and distinguished types, is so permeated by our demand for an end, what use do we see in those who beguile us by what we are presented with as their own obsolescence? Is our talk of them having to grow up not a charitable deed? Do we not want them to be one of us?

The threads covered by this narrated agonism between old and new, elder and young, mature and flimsy, propriety and vitality are addressed one by one by Janikovszky. What then mediates in the end? We must not imagine the “No” of a declaration of the need to grow up as substantive. It has no bearing on the situation, but does introduce a change of a second degree instead of a first one, which otherwise would have been the aim of the statement: it affirms something of an affirmation that itself affirms something about an object. It posits the essential existence of something lying elsewhere rather than with the place or person where and with whom it originally sprung. To grow up, then, can in no way suggest a state. In fact, it can only imply a process. Our metaphysical considerations have to reflect indeed the same balance: we are exposed not to an evenly formatted change of individual degrees in a sequence, but a disorderly, irregular and frenzied space of jumps, plunges, ascensions, turn-arounds, functionings, arbitrary choices. Our hopes of an end do not thereby cease. We have no benefit in attempting to abandon such a notion, and neither does this precursion recommend anything of the sort. What matters is that one cannot force another to hurry with growing up. Better yet, let us affirm not what may be merely an absence of a given kind concealed in a neglected and unaccounted-for end. Let us affirm, in all its unfolding disinterest of what comes next, the powerful sweep that life has on us in its critical moments, so that even in a moment of despair, one may still retain a potential for change.

Note from the editor: The following is the unedited translation of a work by Janikovszky carried out by Sámuel Vető.

“Who’s this kid more akin to?”

By Eva Janikovszky (1999)

Da tends to warn me so many times to beware not to have him unleash his wrath upon me.

But nearly each and every time he says that, it is always too late.

By that time his wrath is always already out, so it doesn’t even matter.

As long as I was small and smart and kindly and pretty, they always knew who I

resembled the best. Grandma always said: “By God, looks just like her mother!” Grandpa

always said: “I’ll be damned if it’s not his father’s!” Uncle Fergus said by and by: “They’re

exactly like poor Jemima down to the spot!” Me Da uttered: “As if I would be looking into

the mirror!” And finally me Ma added: “Just maybe we’re also a bit alike!” As long as I was

small, and had more wits than those who were grown, me Ma used to write down into a

notebook the times when I lied on my stomach before successfully turning around to my

back, the time when I first sat up by myself, or when I managed to stand up in the playpen,

when I first drank from a mug, and what the first word I ever said was. As long as I was small

and adorable, everybody talked to me like so: “The apple of my eye! My only sweetheart! My

little star! My one and only nightingale! Let me grab those pretty fingers! Let me kiss those

tiny feet! What did I bring to my one and only today?”

As long as I was small and charming, me Da used to stick into his album – so that

everyone may come and wonder – the photos of how I looked when I was three days-, two

weeks-, four months-, or one year-old. This was also during the time when I grew out of my

first pair of shoes which then were placed upon the shelf that was above me Ma’s bed, or

when my Grandma cut the first tuft off of that beautiful golden locks of mine, and when me

Da decided to put away into his purse the first ever drawing I drew for him. As long as I was

small, everybody got around to see how much I’ve grown, what good thing I had said again

or had in mind, or to just witness how clever I can be. And me Da took photos of me in the

zoo, on the playground, with Caesar (the giant dog who didn’t scare me to bits at all) or with

Aunt Marjorie (who, on the other hand, did), and during the end-of-year celebration in the

daycare when I received most of the applause. All of this is in spite of the fact that, sadly, I

didn’t look at all interested in what was going around me: Neither did I give a damn about

giving the impression of being present, nor did I even pretend to care that I had a razor-sharp

wit on any of the photographs.

As long as I was small and smart and kindly and pretty, anybody who’d ever seen me

said: “What a success story! You can most definitely be proud of ‘em!” And even though the

family pretended: “Come on, any kid is nice in their own way!” – they admitted among each

other that there is a limit to what can be denied. It is indeed a rare thing to have a kid who is

so nice and so smart equally in the same way. Because they could raise for example the son

of that poor Donna’s, or that daughter of the unfortunate Smiths’, and when – in the middle of

these disputes – my Grandma realized that little Desmond wasn’t even mentioned, everybody

agreed that in the case of poor little Desmond, it was best to leave it that way. Dear Ma and

Da in such times always smiled and said, of course, any kid is fit enough to become rational.

Ever since I’ve grown, and I had started speaking nonsense, and had become

unbearable, and had turned out miserable to even look at, anybody who sees me cries on: “Is

this supposed to be your son? Just baffling! I can’t even recognize him!” And then the family

feels ashamed, because of course, they didn’t realize that I would also become rational. Just

not in the way they had hoped. Ever since I am grown, absurd, foppish, and ungainly, the

only thing they’re doing is sitting around in the room and letting out humongous sighs, trying

to figure out who this kid might be akin to. Grandma says this: “I haven’t the faintest clue,

but surely it’s not his mother!” Grandpa replies: “Hell if I know, but it’d be lunacy to suggest

that it’s his father!” Uncle Fergus utters: “What luck that poor Jemima did not live to see this

day!” Da says, rebuking: “Now at least his mother knows what happens when we grant him

everything!” Ma says, reprimanding: “Well you are his father, why don’t you give him a slap

already?!”

And even though the family knows more than well that any teenager is intolerable,

they agree among each other that what’s enough is enough, that even their own patience has

limits, and that things cannot carry on like this. The only thing they are puzzled by is how to

carry on otherwise. According to Grandma, somebody inevitably has to tend to this kid,

because he is growing like a wild mushroom exposed to the downpour of the early spring.

Grandpa claims one has to discipline this kid, because duty comes first. Aunt Marjorie is of

the opinion that somebody has to sort out who this kid gets to make friends with, because it is

common knowledge that if one sets their mind to gather thistles, they sure too can expect

prickles. Me Ma says this kid should get more sleep, otherwise he will never get any rest. Me

Da thinks this kid should study more, otherwise he will not amount to anything. When Uncle

Fergus reflects, he says it’s sad, because – of course – in their family everybody was normal,

and as such he is afraid that I have the blood of Ricky in me. I asked them who this Ricky is,

but everybody agreed that I have nothing to do with who, or rather, what he is. I dreamt a lot

around those times about this Ricky, but then Grandma told me not to give credit to Uncle

Fergus. Ricky was a good lad who had sadly trodden down the wrong path, said she, as she

showed me a picture of him. Have not dreamt of him since.

Ever since I am grown, absurd, foppish, and ungainly I simply just cannot be talked

with. But they warn me nevertheless. Even if they know that talking to me is like talking to a

wall. I have no idea why the wall does not bother replying, I for one could not bother less

because I know that only trouble is to be gained from that. I could not give a fair reply ever to

anything for the life of me. When they ask me: “My dear son, what are you using your head

for?” I could only say in response that it’s the primary tool for giving headbutts, or growing

my hair out, or that it is where my ears are, which I can even move. And they of course could

not get any more upset from these half-assed answers because they have told me so many

times already, over and over, that it is for thinking. When they complain that only if they

knew what I have been doing over the entire afternoon once they see that I am only beginning

to do my school homework late into the evening, I could potentially tell them that during the

afternoon I recorded three new songs on tape, which I listened to time and time again, then

tried to write down the lyrics for which I had to look up a dictionary in which in turn I had

found a comic book that then reminded me of my own collection of comic books enclosed

within a giant envelope, that of course was tucked away somewhere because we always clean

everything up, which is why I made a comic book envelope-holder for the comic book

envelope because nothing is ever lost in our house and which – once I’ll find the comic book

envelope – I shall be using hereafter, and really, I must admit, the comic book

envelope-holder turned out to be pretty neat, the only sad thing is that I accidentally poured

some liquid glue onto my desk while making it and then I had to search for some gasoline to

have it rinsed off and once it actually did rinse it off, it also destroyed the table varnish on top

that I had to apply a new layer to, but as I found the container the varnish was supposed to be

in I also saw that something completely different was actually there because everything is

mixed together when it comes to containers, so I had to find some sandpaper to refresh the

whole thing which made me think about the possibility of inventing a new type of varnish

you would not have to apply sandpaper to and which instead has a brand new layer of varnish

below it. Maybe it could have a third extra layer below the second one, but none of this is

certain. This whole thing made me remember that there are three problems from chemistry

class which have to be done by tomorrow, but I had no clue which three out of all possible

ones will I have to do definitely, so I dialed up Franklin, because he always manages to

remember stuff like this so fantastically and he really knew, so then I decided to play the

three songs into the telephone that I just recorded so that he may actually hear something

that’s actually good for once and that was when the moment the parents came home. Now, if I

say all of this, the only thing they would actually remember is that I ruined the table-top

again. So I just shrug it off, which makes them retort: “I am just baffled by your tempo, I

have no idea where you get it from!” As if I wasn’t able to make sense of anything on my

own. They will always say in the end anyway: “I don’t know what kind of a kid you are!” But

then again, they all know what kind of a kid I am, all of them, except me.

Grandma says that my nerve is the thing that causes me worry, Grandpa argues it is

the lack of sport, Aunt Marjorie claims it’s anxiety, Uncle Fergus insists that it’s my own

disregard for everything, Me Ma thinks it is the fact that I’m overworked, Me Da considers

that trouble is bound to arise when I stop using my head. On the other hand, they all

completely agree that I haven’t an ounce of consideration for others. Now I don’t know what

they exactly mean by consideration. But my throat always sores up when they play the

national anthem before the games or when we end up winning and they pull up the flag; and

even now, I still keep my old teddy-bear on my room’s shelf and I always feel sorry for the

fish that I catch with my rod. And it’s not true that it does not even cross my mind to stand up

and help around in anything, because even last time I did the dishes and washed up the floor

at Beth’s place once the party ended. Beth’s own grandma said that Beth, as a girl, could take

me as the right example – an utterance that she later came to regret when Beth, as an act of

vengeance, waited for her to emerge from the convenience store to then grab onto her

groceries and carry them home. From that point on, I could also learn from the example that

Beth showed, who, despite not being the most glamorous beauty alive, is at least considerate.

Nevermind anything I could say though, because after everything I could say, they still

wouldn’t understand what and why exactly do I see so much in that Beth girl, when I could

also look to that daughter of the Smiths’ who just happens to live in the neighborhood; or the

sister of that Desmond for that matter, who is indeed somebody more serious. And why do I

not fancy making friends with Desmond himself in the first place, from whom I could only

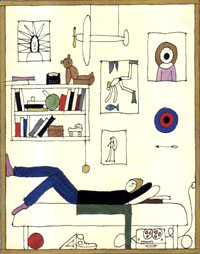

learn good things? After all, neither is it normal that I constantly sit rotting away in my room

and have the tape-recorder bellow into the bad, unhealthy air. When they were my age,

neither Da nor Ma did lie all day on the sofa, or sit with crooked backs against the wall next

to the tape-recorder, but rather, after lunch, they immediately started doing their homework so

that once they finished up, they could go out to the field and breath in the good air. In my

opinion, they did so because none of them owned tape recorders.

When I play the tape recorder, Uncle Fergus just laments how I used to love music

back in the day, while Ma repeats that neither is it proper that I haven’t got any friends. The

fact is that they can’t fathom that I actually have some of the sort, it’s just that they too are

sitting at home with crooked backs, in the bad air, bellowing the tape recorder into it all day

long. They also just might be lying on their backs on their own sofa. And of course one thing

that does not appear to cross neither Da’s or Ma’s mind is that if I had no friends at all to

begin with, I wouldn’t be able to bellow the tape recorder all day long in the first place,

because then I couldn’t count on anyone to lend me their tapes.

Da says he is happy that I have friends, but he would like to see who those people

might be. Then when they actually show up, he cannot even stand to look at them. Because

what kind of a pigpen is the sort where none of them wipe their feet when they enter – but all

of them have their hands in their pockets; that none them are able to greet him properly – but

are glad to take off their shoes; that none of them have not one normal word to say because

all they do is either neighing like horses, or sit in silence like piles of trash. Because neither

Ma nor Da had tape recorders or record players or pocket radios when they were my age, but

instead they had their own respective good companies who they used to go on trips, or play

tabletop games with, and to whom they always used to talk to like normal people. Each and

every one of their friends became notables, except for those ones who deviated. Grandma

cannot deal with the fact that when my friends are concerned, it is impossible to guess which

one is a boy and which one is a girl, because all of them are dressed in the same costumes to

the extent that their mere presence is already a bad sight. And if they exceptionally do not go

around in the same type of clothing – and thus it can be determined who is a boy and who is a

girl –, then the trouble is that: “It’s unbelievable how these kids are behaving nowadays, do

those girls even have a mother?!” I do have to say, it’s interesting that Beth’s grandma

pointed out the same thing when I was over at their place for the first time, except she did

know that I was a boy.

When everybody already saw my friends at home, Grandpa said I really could have

that much in reserve to admit that my parents are working people, thus they also deserve this

one Sunday, with the only other day for them being Saturday, to finally have some rest, and

that at least during this time they’d like to have silence and peace of mind at the house. And I

had that much in reserve to admit that, so I grabbed the tapes and was already headed to a

friend’s place. Ma was delighted that I finally moved out of my room for once and that I

won’t be sitting with a crooked back against the wall in the bad air and that I won’t be lying

on the sofa all day long. But she wanted to know my friend’s name, address, the contents of

his last grade transcript and their father’s job, because even if she couldn’t care less whose

son we’re talking about – because something like that is undeniably trivial –, she stood firm

that I won’t be taking the tapes anywhere because they didn’t buy something so expensive to

only have it ruined by somebody else. All of this is because one of my friends, Skippy, took

the tape-recorder away once and the thing happened to malfunction simultaneously. Da

reiterated that: “I knew it, I knew it, what a self-fulfilling prophecy!…” Because grownups

already know everything. They always know the time when I’ll fall off of that one thing,

when I’ll break the other, when I’ll ignite it, or that I’ll be pouring it out, that I’ll also get

cold, or that I’ll ruin it, and even that it’ll never, almost never end well. The only thing I don’t

get is the reason why they get mad at me when they turn out to be right in the end. I’d never

prefer to know the end of anything at all, except the answers for the problems from math

class, but I can always call Franklin for that.

Ever since I’ve grown, and even my five year-old sister has more wits than I do,

they’re also curious about how exactly I’m trying to picture life out of all things. Almost as if

I was supposed to be doing that when I am loudly bellowing the tape recorder, when I leave

my muddy shoes in the hall, when I am about to lend the camera to Skippy, when I come

home late, when they cannot wake me in the morning, when I take too long in the bathroom,

when I watch the TV all day and when I spend my weekly allowance first thing on Monday.

Obviously these are all of the wrong moments for me to picture life, because whenever these

moments happen, I also happen to be pretty preoccupied with so much other stuff. I try to

picture life once I sit down to study, because that is when I actually have the time; or when I

come out of the movies because that is when I am in the mood; or when Beth comes around

and whistles me down, because that is when things get going.

Personally, life is pretty tolerable and it’s completely unnecessary to trouble anybody

with it. I for one feel great being alive, even if it’s not the first thing that occurs to anybody

else when I’m being looked at. The reason why I think it’s not apparent, is because otherwise

none of them would be repeating that so many others would be happy to go around in such

expensive winter coats, to learn various languages, to drink hot chocolate every morning, to

own this many books, toys and clothes, and be so cherished by and cared after by their

parents. The only problem is that in my giant, good deal of a life, I don’t even know what I

should be doing. Okay, maybe this isn’t true, because I always know what I should be doing

in this giant, good deal of a life. I also know that once I’ll become an adult, I’ll be eating all

of that tasty food that I’m now mostly just tinkering away with, that later on I’ll be grateful to

Aunt Marjorie who always wanted the best for me, that I’ll be cherishing the money that I’ll

have been working for, that I’ll cry after my childhood when everything was plenty, and that

I’ll be learning – sadly at my own cost – how hard is it really to live. The only problem is that

none of these things are important for me to hurry with growing up, and besides, I love

leaving everything to the last minute. So it’s all for naught when Da asks me about what kind

of a man I’ll wanna grow up to be with an attitude like this, because I just cannot imagine

anything like it, even though I already spend hours pondering. Maybe I’ll grow five more

inches, but three more certainly, and maybe I’ll sport shoes one or two sizes greater than the

ones I do now, and I hope my muscles will get stronger and then have a wider shoulder,

maybe also try having a beard for once. But I definitely will resemble Da – and even Ma – a

little.

And once they’ll get old, and once they’ll be sitting out on the benches of a local park,

then they’ll be the ones to show around my pictures, saying that: “This is our son, you

certainly must have seen him on TV and read about him in all the newspapers, because he is

world famous, yes, indeed, he is the one who reached it and traveled around it and discovered

it, won it and surpassed it and knocked it out, found it and captured it and saved it, defeated

it and liberated it and declared it, lived through it and wrote it and composed it!” And then

everybody will be sitting around them and they’ll just stand and wonder like: “I’ll be

damned, is he your son?! How astounding! You sure can be proud!” And then finally, not

even Da will say: “I knew it, I knew it, what a self-fulfilling prophecy!”

Other posts that may interest you:

Discover more from The Sundial Press

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.