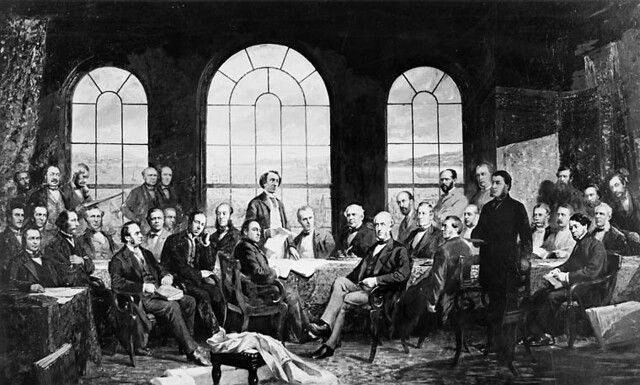

Illustration Legend: The Conference at Québec in 1864, to settle the basics of a union of the British North American Provinces. (James Ashfield, original painting by Robert Harris) Library and Archives Canada / C-001855

Doug Ford, the premier of Ontario, ignited a national debate in 2021 when his government passed legislation imposing strict limitations on third-party political expression for a full year prior to an election, effectively curbing criticism of the government. But unlike most leaders in the Free World who would face an onslaught of lengthy court battles, the head of Canada’s most populous province had an easy fix. He invoked the Notwithstanding Clause—Section 33 of Canada’s Constitution that allows provinces to override certain Charter rights for up to five years, effectively sidestepping the courts’ scrutiny and shielding his law from constitutional challenges.

A common Western notion of constitutional democracies rests on the idea that, regardless of political fashions, passions, or pressures, certain indivisible rights must remain inviolable. Constitutions act as guardrails, shielding against the tyranny of the majority, governmental overreach, and the worst excesses of power. They are designed to endure beyond the whims of expedient leaders or shifting public opinion. By defining the relationship between the citizen and the State, a constitution serves as the fundamental guarantor of legality, ensuring that State power cannot be exercised without conforming to its principles. But what happens when the unity of an entire nation hinges on a precarious balancing act, one that permits democratic norms to be subverted by majority fiat?

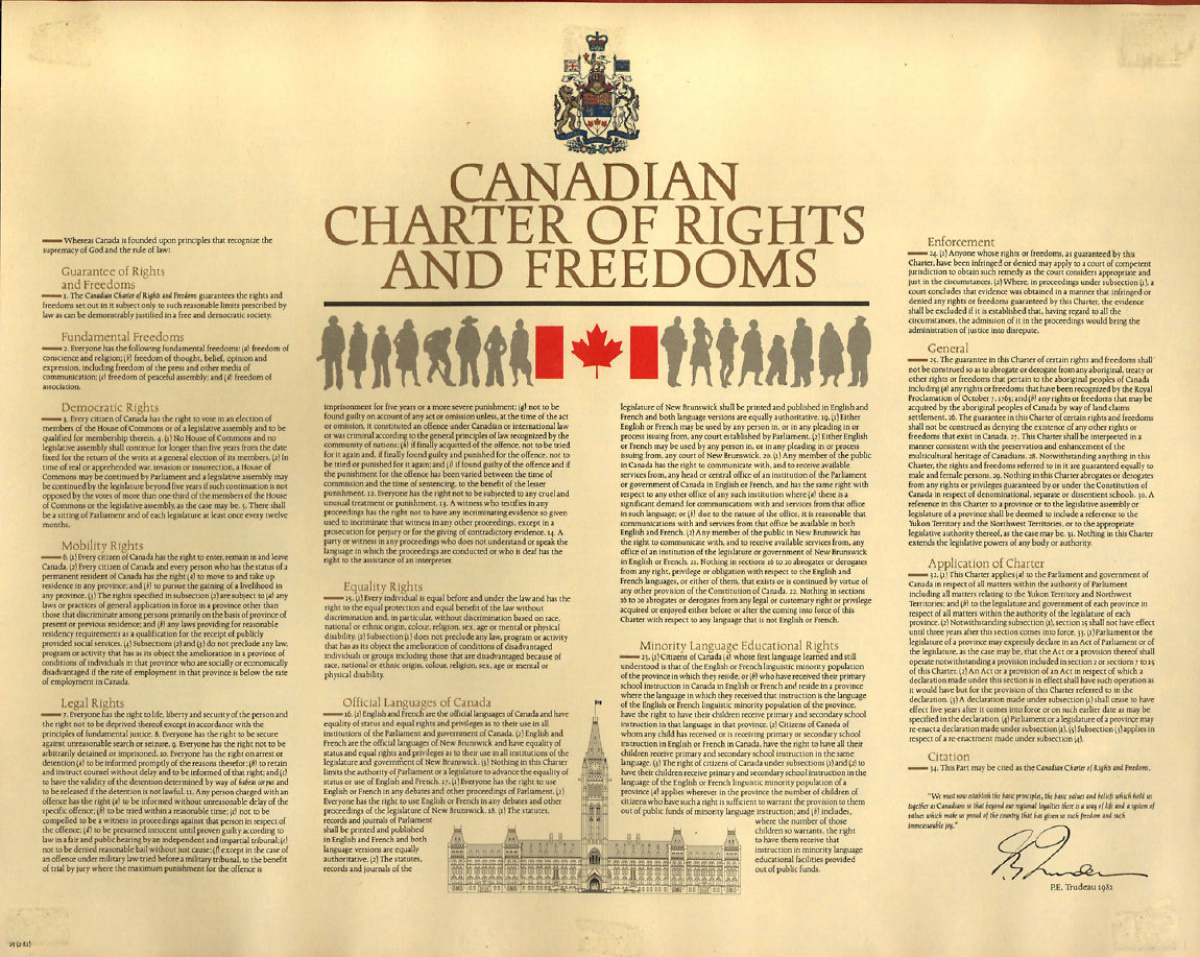

In Canada, federal and provincial legislatures can subtract, with a specific declaration, a law from the scope of certain constitutional protections around legal and political rights–within confines of section 2 or section 7 to 15 of the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms–notwithstanding judicial review.

To offer a concise overview for non-Canadian readers: when Canada was created in 1867, its constitution, in essence, was a piece of British law. Britain only granted the country full autonomy over its affairs in 1931, except Canada did not have a constitution of its own and Britain continued to wield sole amendment discretion. Constitutional sovereignty was an imperative for the to-be Prime Minister Pierre Trudeau; a failed separatist referendum of 1980 in Quebec opened a window for him to convince the provinces to attempt to do just that.

When we discuss the Constitution today, the focus is often on the Charter of Rights and Freedoms—the instrument the Ontario court relied on to invalidate Mr. Ford’s restrictions on political expression. Yet, in 1980, when Prime Minister Trudeau convened the provinces’ premiers and initiated constitutional negotiations, the Charter was far from a priority. By 1981, only the federal government, Ontario, and New Brunswick supported the entrenchment of a national charter of rights. Like Mr. Ford, the remaining premiers—that came to be known as the Gang of Eight—opposed it, arguing that codified rights would erode Canada’s tradition of parliamentary sovereignty by subordinating legislative authority to judicial interpretation, altering the nation’s constitutional balance.

From a historical point of view, creating a national bill of rights required a compromise to prevent the opposition of all provinces, especially Quebec. Quebec in no small part has been a dispositive determinant of the Canadian constitutional order. The British North America Act of 1867, while creating a federal structure, was primarily intended to unite the British North American colonies which meant accommodating Quebec’s demands for greater autonomy, particularly through the transfer of jurisdiction over “Property and Civil Rights” to the provinces, ensuring the preservation of Quebec’s civil law system within a broader common law federation. The founders feared that if the Confederation wasn’t constructed in a way that balanced the autonomy of the provinces with the strength of the central government, it might unravel. The Quebec Conference and the Charlottetown Conference, key precursor meetings to the Confederation in 1864, involved serious discussions about how to ensure that the provinces had sufficient self-governance to maintain their loyalty to the union and avoid the disintegration of the infant nation. Looking around the rest of the world, we find ample evidence that would have been the cause of amplifying, not modulating, their fears.

The 1982 patriation of the Constitution marked an inflection point in Canada’s full independence from Britain. Quebec’s refusal to endorse the new constitutional arrangement threatened national accord at a historic moment. The Notwithstanding Clause emerged as a constitutional safety valve, a compromise aimed at placating provincial concerns—especially Quebec’s—over the powers granted by the Charter. Even though this maneuver did not go far enough to quell all grievances of the French-speaking province—such as claims to a constitutional veto— in retrospect it helped keep the impulses of the moment from spiraling.

This provision has since been grounds for forceful debate stemming from legitimate fears of enabling precisely the kinds of abuses the Framers sought to prevent. An order freezing financial assets from peaceful protesters to muzzle dissent? Override. A law mandating mass data collection on citizens’ private communications to combat perceived threats? Override. An order directing the Royal Canadian Mounted Police to conduct tampered investigations on political opponents? Override. Override, override, override.

Copy of the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms. (Department of Secretary of State, Canada)

As the Canadian founders recognized, the notion that courts inherently act as neutral, sanitized arbiters of public consensus crumbles under scrutiny—not least with the neighbouring example of the overturning of Roe v Wade by the U.S. Supreme Court, which did away with over 50 years of precedent and yes, overrode the overwhelming public support for women’s right to choose. Even in Canada, where the Notwithstanding Clause has been selectively invoked—such as in Quebec, where legislators outlawed the public display of religious symbols under the guise of “laïcité,” or secularism—parallels can be drawn to France’s own such ban in 2010. When constitutionally challenged, not only did France’s domestic courts uphold the move, but so did the European Court of Human Rights in SAS v France (2014). A key distinction, however, lies in Canada’s five-year sunset clause for parliamentary interventions under the Notwithstanding Clause, which ensures that such measures must be periodically reassessed. In an electoral democracy like Canada, ultimately voters retain the power to hold leaders accountable for these overrides at the ballot box. In jurisdictions with judicial veto, rights can be stripped away with minimal recourse, unless the apex court reverses its own precedent or experiences a significant ideological shift on the bench.

The issue was a dealbreaker for the combative Gang of Eight.

Section 33, or the Notwithstanding clause, was devised as a way of solving that deadlock, a compromise to keep the nation together. The Canadian statesmen succeeding the founding generation were keenly aware that the challenges of keeping a democratic union remained just as great after 1867 as they were before.

In a country as vast as Canada, with regions extraordinarily diverse in their economic interests, regional loyalties, and ethnic and religious attachments, credit then is due to Mr. Trudeau and his opponents for settling intense differences through democratic means–an achievement made all the more remarkable when comparable arguments sundered societies elsewhere and confounded the goals of stable, consensual governments.

Doug Ford’s invocation of the political maneuver serves as a reminder that Canada’s founding compromise remains a living, breathing tension. The mechanism designed to keep the Canadian experiment from fracturing in 1982 now seems to allow office-holders to bypass guardrails with unsettling ease.

But perhaps that is the paradox Canada must live with. The Canadian compromise was never about perfect harmony; it was about making a union work despite deep divisions.

The Constitution is neither a self-actuating nor a self-correcting document. The Framers made it to be uniquely rejective of complacency and dependent on constant action on people’s part, admittedly more than most nation-builders would have dared. We will continue to have the democratic government they created as long as we can keep it that way. Only as long as we can keep it that way.

The clause is not absolute and cannot be used to cancel democratic processes, restrict mobility, erase language protections, undermine Indigenous treaties, or roll back progress on gender equality. It enjoins a set of values and principles enshrined in a document that also allow for self-renewal, and moral growth. We carry the scars of residential schools and state-sponsored exclusion, but came out of them a people that, through amendments (in particular the 1982 Constitution Act), made the Constitution better and stronger. One that finally grants equal protection of the laws to all the people, not just some of the people.

If there is a lesson in this, it is that the staying power and dynamism of the Constitution comes from no permanent rule other than its faith in the wisdom of ordinary people to govern themselves.

The question of whether the Notwithstanding Clause has outlived the crisis it was designed to settle is one that should no longer be deferred. It is time.

Meanwhile, when the judiciary is attempted to be overridden, the responsibility for accountability shifts to the people. The ballot box becomes the primary tool for checking government power. In Canada’s system, guided by the Charter, the people themselves become the check and balance.

Other posts that may interest you:

Discover more from The Sundial Press

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.