You may write me down in history

With your bitter, twisted lies,

You may trod me in the very dirt

But still, like dust, I’ll rise.

Maya Angelou

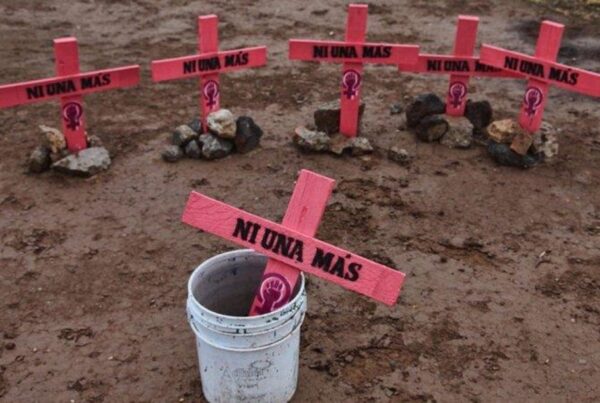

Often undervalued, invisibilized or ignored, women have always been put to a second level when we create narratives and write history. However, they have always participated in social and political movements across history, rising from the ashes to become major figures to admire.

Millions of women mobilized against President Donald Trump in the United States in 2017 and President Jair Bolsonaro in Brazil in 2018, viewing these leaders as dual threats to women’s rights and their countries’ democracy. In Poland, women took to the streets during the COVID-19 pandemic to protest the ruling Law and Justice party, their activism catalyzed by the government’s aggressive rollback of reproductive rights. In Belarus and Myanmar, women spearheaded nonviolent civil resistance movements against authoritarian power grabs, mobilizing at great risk to their safety. Women in India, Iran, and Sudan similarly fronted mass protests against antidemocratic and exclusionary regimes.

In other words, women are unquestionably on the frontlines of change, raising their voices of resistance against rotten systems, unfair regimes, and human rights violations.

Therefore, this article will portray four women figures who were brave enough to stand up for their beliefs, leading protests, mobilizing others, raising awareness, and fighting for justice, while dealing with discrimination and oppression. Because, whether intentionally or unintentionally, discrediting women’s role across these resistance movements is a form of gender-based violence which is shaping History through a patriarchal and masculine lens.

May Sabe Phyu (Myanmar)

Born in the late 1970s, May Sabe Phyu is a Kachin activist and human rights defender from Myanmar. She is active in promoting freedom of expression, peace, justice for Myanmar’s ethnic minorities, and anti-violence in Kachin State. Her work centers around combating violence against women and girls and advancing gender equality.

Born into a multi-ethnic family, May Sabe soon learned about the reality of ethnic discrimination and ethnicity’s inextricable connection to armed conflict in Myanmar. While her mother was born in Kachin State, her father grew up as a member of the Bamar, the dominant ethnic group in the country, which has systematically excluded, marginalized, and oppressed ethnic minorities, including the Kachin, for decades.

“As a mixed-blood child, I was always seen as an outsider in my own community. This discrimination made me think a lot about the origin of Myanmar’s ethnic divide and inspired me to become a peace activist and advocate for ending inequality and violence, especially in remote areas.”

After living under a military dictatorship for most of her life, May Sabe knows that men’s hunger for power and authority can result in increased violence and the adoption of policies that fail to address the needs of women and girls. While most people in Myanmar still believe that a woman’s place is at home and that women lack the skills to lead, May Sabe is a firm advocate for feminist leadership, who strongly believes that women’s negotiation skills are critical to achieving sustainable peace.

“When women get involved in decision-making, it’s not just good for women and girls, but for everyone. They understand the needs and challenges of the wider society and make decisions seeking the common good. When they get to participate in peace negotiations, women serve as medicine: they talk to both sides, try to negotiate, and make people listen to each other. A lot of evidence-based research, not just my experience, highlights this.”

In 2008, she was instrumental in forming the Women’s Protection Technical Working Group during the response to Cyclone Nargis. After the disaster relief situation stabilized, the Working Group evolved into the Gender Equality Network. As Director of the Gender Equality Network, May Sabe Phyu carries out high level advocacy on women’s rights and oversees the implementation of the network’s strategic initiatives to promote gender equality policies. Through the network, May Sabe Phyu is currently co-coordinating a law reform process with various stakeholders to draft the country’s first law to prevent violence against women by creating new criminal offenses for many types of violence, civil remedies, and a regime to enforce the law.

By taking a deeper look at her engagement in activism in Myanmar, we observe her activism story began in the early 2010s with the foundation of the Kachin Women Peace Network, where she used to raise awareness in order to improve the situation of internally displaced persons (IDPs) in Myanmar. Moreover, she advocated for inter-ethnic trust-building and women’s involvement in the peace process to resolve Myanmar’s civil conflict. As her family and herself received more death threats and false accusations (corruption, conspiracy, trahison), she started to become more involved in protest movements (mainly against government policies and actions).

Following the February 1, 2021, Myanmar military coup, the situation worsened drastically for human rights activists as well as for women’s rights. Thousands of people started protesting against Myanmar’s increasingly authoritarian regime. Activists’ focus shifted toward democracy, sparking street protests to restore democracy.

According to a Women’s League of Burma report, women comprised more than two-thirds of the protesters in the aftermath of the coup. Women and girls played key roles as medics in conflict zones and supported displaced populations, primarily women and children. Despite facing systemic violence, they emerged as prominent leaders in the resistance and social movements against gender-based violence. In the civil disobedience movement, women employed creative tactics like hanging sarongs, underwear, and red sanitary pads to exploit soldiers’ superstitions, slowing down their military advances and giving protesters more time to mobilise.

“Women’s rights have never been part of the military agenda” said May Sabe Phyu, “This time, women are standing at the front and, in many cases, they are leading the protests.”

For her leadership in advocating for equal rights of women, ethnic and religious minorities in Myanmar, May Sabe Phyu was honored with an International Women of Courage Award by the State Department of the United States of America in 2015.

In fine, May Sabe Phyu is an unquestionable voice of resistance. Through her several years of activism, she has demonstrated how important it is to constantly be fighting for women and minorities rights, as we can not take them for granted. A change in the political regime can make years of activism disappear.

Razan Zaitouneh (Syria)

Born in the late 1970s, Razan Zaitouneh is a Syrian human rights lawyer and civil society activist. Soon after graduating from law school in Damascus in 1999, she started working as a lawyer to defend political prisoners. In the same year, Razan was one of the founders of the Human Rights Association in Syria (HRAS). In 2005, she established SHRIL (the Syrian Human Rights Information Link), through which she continued to expose human rights violations in Syria. Moreover, Razan Zaitouneh was an active member of the Committee to Support Families of Political Prisoners in Syria.

Therefore, when the revolution kicked off in 2011, she was among the first activists to call on the Syrian government to release political prisoners in an open letter published a day after the first major protests on March 15, 2011.

“We are facing one of the most brutal regimes in the region and the world with peaceful protests, songs of freedom — chanting for a new Syria,” she said in a 2011 video statement. “I’m very proud to be Syrian, and to be part of these historical days, and to feel that greatness inside my people.”

Back then, 33-year-old Zaitouneh became directly involved in organizing protests in Damascus and other cities across the country. Her efforts contributed to the formation of the Local Coordination Committees, which were instrumental to early democratic efforts in Syria. Her opposition to armed resistance set her apart from many of her contemporaries — some of whom would go on to actively lead organized violence against the regime.

In April 2011, only a month after protesters had taken to the streets against President Bashar Al-Assad, the young lawyer co-founded the Violations Documentation Center (VDC), which continues to operate today. The center reports atrocities committed by security forces, including the kidnapping, arresting, torturing and killing of peaceful protestors. She was one of few sources for the international media who documented the brutality of Bashar al-Assad’s regime towards the Syrian people.

Nonetheless, she eventually found that she could no longer work effectively in Damascus with Syria’s secret police stalking her across the capital. In May 2011, her husband was arrested at their home and held for three months. As a result, she went into hiding for two years after being accused by the government of being a foreign agent.

At that time, female activists in Syria were jailed and tortured. Stories of rape spread like wildfire, terrifying to most women activists. Despite this brutality, many women inside Syria continued their fight. But they were also keen to use precautionary measures to protect themselves, including covering their faces while in protests so that they could not be identified by security forces.

By April 2013, Zaitouneh decided to flee for the rebel-held town of Douma on the outskirts of Damascus in the hope of continuing her work more freely.

Her arrival in Douma was challenging. Zaitouneh and her colleagues quickly figured out that their presence in the area was not welcomed, largely because she also investigated abuses committed by armed rebel groups, including Islamist militants.

“We did not do a revolution and lose thousands of souls so that such monsters can come and repeat the same unjust history,” Zaitouneh wrote. “These people need to be held to account just like the regime.”

By summer 2013, Zaitouneh was being targeted for her work. But her refusal to wear a headscarf or adhere to conservative values also triggered hostile responses from some of the rebel groups.

On December 9, 2013, armed men stormed her office in Douma. They abducted Zaitouneh, her husband Wael Hammada, fellow colleague Nazem Hammadi and Syrian activist Samira al-Khalil. They would become known as the “Douma Four” in the wake of their disappearance.

A criminal complaint holding Jaish al-Islam responsible for the abduction was filed in France by the International Federation for Human Rights (FIDH) and the Syrian Center for Media and Freedom of Expression

Until today, her fate remains unknown. The disappearance of Razan, her husband and colleagues remains one of the great unsolved mysteries of the Syrian revolution. Nonetheless, her fight for Syria’s pro-democracy movement continues nowadays through her work and her fellow colleagues.

“People’s rights and treating them with justice is not something open to interpretation nor is it a point of view,” Zaitouneh said in the last article she wrote before her disappearance.

Leymah Gbowee (Liberia)

Born in the early 1970s, Leymah Roberta Gbowee is a Liberian peace activist and Nobel Peace Prize laureate who led the women’s non-violent peace movement, Women of Liberia Mass Action for Peace, that helped bring an end to the Second Liberian Civil War in 2003.

Originally born in central Liberia in a close-knit rural community, she moved to the capital city Monrovia with her family when she was a child. A serious student, Leymah Gbowee had just graduated from high school and was preparing to study medicine when her world turned upside down.

In 1989, General Charles Taylor led an armed uprising against the government of President Samuel Doe. The First and Second Liberian Civil Wars — two wars separated by a brief ceasefire — would rage on for 14 years, tearing the country apart. The day the fighting broke out, Leymah was separated from her parents for several days. The war traumatized her mother and forced the 17-year-old girl to become a caregiver for her mother, her sisters’ children, and nearly 20 friends and extended family members who sought shelter in the Gbowee home. She turned, in her own words, “from a child into an adult in a matter of hours”.

As the fighting of the First Liberian Civil War ended in a ceasefire, the country settled into a brief period of peace under the dictatorship of President Charles Taylor. The United Nations Children’s Emergency Fund (UNICEF) initiated a program to train social workers to help others recover from the trauma of war. Gbowee enrolled in the program and spent the next few years counseling women who had been raped by soldiers and children who had seen their parents murdered.

She came to believe in women’s responsibility to the next generation to work proactively to restore peace, and she became a founding member and Liberia Coordinator of the Women in Peacebuilding Network. Inspired by a dream and as a person of faith, she started recruiting women in markets, churches and mosques to unite Christian and Muslim women in a single movement, staging massive demonstrations and sit-ins in defiance of the orders of President Charles Taylor. This unprecedented coalition with Muslim women gave rise to the interfaith movement known as the Women of Liberia Mass Action for Peace.

Dressed in matching white T-shirts and white hair ties, the ”Women in White” defied the police and stood along a route where President Taylor had to pass them every day. With more than 2,000 women gathered outside his office, Taylor finally granted them a hearing in 2003. As the recognized leader of the women’s movement, Gbowee took charge to make their case to President Taylor.

She led a delegation of women to Accra (Ghana) in June 2003 where they applied strategic pressure to ensure progress was made towards peace. At a crucial moment when the talks seemed stalled, Leymah and nearly 200 women formed a human barricade to prevent Taylor’s representatives and the rebel warlords from leaving the meeting hall for food or any other reason until, as the women demanded, the men reached a peace agreement. When security forces attempted to arrest Leymah, she displayed tactical brilliance in threatening to disrobe – an act that according to traditional beliefs would have brought a curse of terrible misfortune upon the men. Leymah’s threat worked, and it proved to be a decisive turning point for the peace process. Within weeks, Taylor resigned the presidency and went into exile, and a peace treaty mandating a transitional government was signed by all parties concerned (rebels, governments).

Leymah’s impact on the world had only just begun. She had emerged as a global leader whose participation was in demand at meetings of the United Nations Commission on the Status of Women and other major international conferences.

In addition to helping bring an end to 14 years of war in Liberia, this women’s movement led to the 2005 election of Ellen Johnson Sirleaf as president of Liberia, the first elected woman leader of a country in Africa. Sirleaf is co-recipient of the 2011 Nobel Peace Prize along with Gbowee and Tawakel Karman. The three were awarded the prize for their non-violent struggle for the safety of women and for women’s rights to full participation in peace-building work.

Morena Herrera (El Salvador)

Born in the late 1950s, Morena Herrera is a Salvadoran feminist and social activist, renowned for her work against her country’s abortion ban.

Active in campaigning for social change from a young age, during the Salvadoran Civil War, (1979-1992), Herrera served as a left-wing freedom fighter. She fought with the Farabundo Marti National Liberation Front (FMLN) against the United States-supported government for over ten years.

She and her leftist comrades were incensed by an autocratic leadership that had ushered in sweeping inequality and a crackdown on civil liberties. As a commander and top military strategist, Herrera risked everything in a twelve-year war that left an estimated 70,000 dead.

Herrera was outspoken on the Peace Accords, signed in 1992, which she saw as deeply problematic for women’s rights in El Salvador. She has said of them: “Those accords left big holes when it came to women’s rights. I realized I had to fight another way. Women’s rights are human rights and they have to be a priority.”

Indeed, the situation for women and abortion worsened over the 1990s. The small Central American country has the highest rate of femicide in the world and one of the highest rates of teenage pregnancy in Latin America. In 1998, abortion became illegal and criminalized in all cases including rape, incest, and those in which a mother’s life is at risk. The country’s powerful Catholic Church and pro-life lobby enthusiastically backed the new law and wielded significant influence among a vastly conservative population. However, the state of reproductive rights in El Salvador was not always so dire. Prior to 1998, abortion was permitted in cases of rape, incest, where a foetus was injured or if the life of the woman was in danger.

It is estimated that between 1998 and 2013, more than 600 women have been jailed for up to 40 years after being accused of having had an abortion. In many of these cases, the women had simply endured a miscarriage.

As the head of the Citizen’s Group for the Decriminalisation of Abortion since 2009, she is today often the only champion for such women, criminalised by the state. She has received death threats and abuse, and faced allegations that she is working for those who want to damage the country.

One of the most outstanding cases Herrera and her colleagues have fought for is a group of jailed women known as “las 17”. A handful have been freed, but the authorities keep prosecuting more women; the number of 17 now stands at 25.

“It’s because the reproductive rights of women are not recognised,” she said, explaining the slow pace of change. “The problem is the lack of awareness about what reproductive rights are, and because of this the [impression] for the majority of women is that they are here just to be mothers. For example, right now, the huge number of teenage pregnancies is brutal. A third of all births come from teenage mothers. And there is another terrible number – those mothers who are beneath the age of 14.”

These young women are more subject to pregnancy complications since they are still growing and maturing themselves. Political figures do not want to discard the ban on abortion because they fear the church and certain organizations such as the “Yes to Life Foundation”. The idea of “a woman’s sole purpose is to be a mother and take care of the house” is a priority for the church and society of El Salvador, leading to the inability for a woman to be in control of her body. To make matters worse, contraception is very hard to obtain for most women and if they do obtain some, it usually does not work properly.

Despite the plethora of obstacles Herrera still has to overcome, she continues to work tediously each day towards a better, consented life for all women in El Salvador. Her work was the subject of a report by Amnesty International in January 2015 and in 2016 she was named one of the BBC 100 Women.

Women are, without a doubt, voices of resistance and resilience across the world, fighting for justice, human rights, democracy, women’s rights, etc. From El Salvador to Myanmar, passing through Syria and Liberia, we have highlighted four exceptional and unique stories of women who were on the frontline of change, determined to fight for their rights.

Ignoring and undervaluing their powerful actions as protesters, advocates, or activists is a mistake that has been perpetrated through centuries, because History is mostly always written by men or with a male-center perspective.

We must not forget these actions are a form of gender-based violence, committed over decades and centuries of patriarchal societies that try to maintain gender roles as they best suit men.

Other posts that may interest you:

- Briser le cercle : les impacts intergénérationnels de la violence domestique

- Milei au pouvoir : quel avenir pour les femmes en Argentine ?

- Les femmes en Ukraine, entre victimes et combattantes d’une guerre sans fin.

- Une dictature du patriarcat : un an après la mort de Mahsa Amini, la répression demeure présente…

Discover more from The Sundial Press

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.