On April 16, 2023, Iveta, a 39-year-old woman, was murdered on a Latvian country road by her ex-husband, Leons Rusiņš, 53, in front of her mother and 6-year-old son. The family had driven out to the nearby cemetery to visit family graves. On their way back, Leons Rusiņš, who had been stalking, harassing, and threatening Iveta since she ended their relationship more than a year ago, blocked the road with his car and attacked Iveta with an axe. Iveta’s family, in shock, went searching for help, while Rusiņš left the scene of the crime and has not been seen since. Iveta bled out and died on the dirt road.

The details of the case revealed in the weeks following the murder showcased the glaring flaws in how Latvia’s justice system attempts to combat gender-based violence and femicide. Iveta’s murder sparked public outrage, and the brutality of the incident left politicians with little excuse for inaction. The society-wide debate that transpired resulted in concrete amendments to legislation, a widespread increase in public awareness of femicide, as well as the ratification of the Istanbul Convention after years of fruitless debates. Despite these advances, the murder also revealed pervasive misconceptions about gender-based violence and the deeply ingrained attitudes that perpetuate it.

As with many other cases of femicide, this too is a murder that could have been prevented. After Iveta left Rusiņš more than a year before the murder, he started to stalk, threaten, and harass her. He followed Iveta to her job, watched as she took her children out of kindergarten. He would send messages with threats to her and her children, sometimes hundreds in one night. When Iveta managed to get a restraining order against Rusiņš, the ex-husband blatantly ignored it. The next day, he attacked her with a knife, leaving gashes on her cheek and arms. Rusiņš was fined for the offense, but this, just the next one in a pile of unpaid fines, did not deter him. Up until the murder, 19 different proceedings were initiated against the man.

Rusiņš’ behavior was not a secret in Jēkabpils, the town of 20,000 where Iveta lived. She had left her previous job in a pharmacy due to persistent harassment from Rusiņš that paralysed her work. At her new job, a position at the Centre for Disease Prevention and Control, little changed. The government agency was paralyzed as occasionally hundreds of calls and threatening emails would flood in from Rusiņš in a day. This behavior is documented in a trail of police reports – from Iveta, as well as her family and colleagues – and court orders that ultimately failed to protect Iveta from the danger she knew she was in.

When news of the incident broke, responsibility for the murder became an institutional hot potato. The Chief of Police pointed out that while the police can take some blame, the prosecutor and courts might have also not been up to par. The President of the Zemgale District Court, meanwhile, laid the blame squarely with the police: on February 8, 2023,, more than a month before the murder, Rusiņš had been declared wanted concerning a case for failure to comply with the restraining order Iveta had against him. If the police had found him, the murder could have been avoided, the district judge said. The Attorney General Juris Stukāns in an interview with the women’s magazine “Ieva” confidently proclaimed that Iveta’s attorney had not exhausted all possibilities for action, a statement that received widespread condemnation, including from the President of Latvia. Despite public calls for resignation, Stukāns remains in office. Finally, select Members of Parliament claimed that the issues do not stem from the law, but its enforcement.

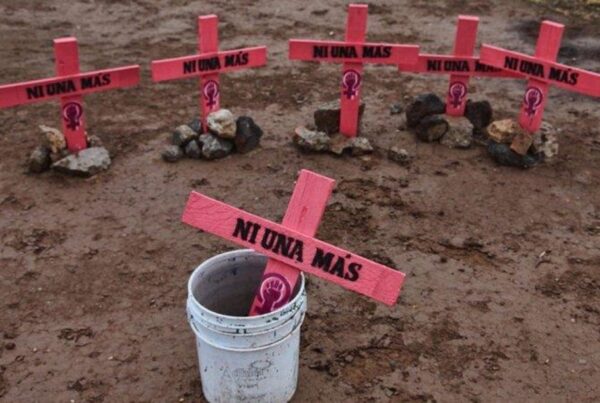

Meanwhile, civil society groups saw the murder as a symptom of a systemic failure to protect women from gender-based violence. In a protest in front of the Cabinet of Ministers, more than a hundred people united in a protest action called Nāves iemesls: sieviete (eng. Cause of Death: Woman), with signs decrying domestic violence and government inaction. Protest leaders demanded a comprehensive review of the mechanisms available for protecting women and called for the ratification of the Istanbul Convention, as the Council of Europe Convention on Preventing and Combating Violence Against Women and Domestic Violence is more widely known.

The Istanbul Convention has been controversial in Latvia whenever discussion about it sparks up in the public space. Whether in 2016, 2018, or in 2021, when the Constitutional Court of Latvia ruled that the Convention is compatible with Latvia’s constitution (an argument many levied against the Convention), the arguments against ratification had remained unchanged through the years.

The primary concern of those against ratification was the term “gender”, defined in article 3 of the Convention as “the socially constructed roles, behaviors, activities and attributes that a given society considers appropriate for women and men”. A public initiative for the non-ratification of the Istanbul Convention, signed by around 13,000 people as of the summer of 2023, claimed that “the Istanbul Convention contains instruments that open the way to overly broad interpretations of the concept of “gender” or “social sex”, threatening not only Latvia’s traditional culture and family values but also the long-term existence of a healthy society”. The public initiative was voted down in the Parliament, but the sentiment expressed by signatories was pervasive in Latvian society.

Over a few months, the ratification of the Istanbul Convention had become a central issue of public debate, with various actors, from social media users to a former president weighing in. A look into the discussion programme “What’s happening in Latvia?” (a popular debate show aired by the national broadcaster) offers a sharp insight into the state of public debate on the Istanbul Convention in Latvia and gets to the root of disagreements that often appear irreconcilable.

When, in the course of the debate, participants are asked where violence against women comes from, conflicting worldviews are put into sharp contrast. Uldis Augulis from the coalition party Zaļo un Zemnieku Savienība (eng. Union of Greens and Farmers) admits that violence, at least in part, stems from gender stereotypes: the boxes our society puts men and women in. These stereotypes cause and exacerbate the belief that men are stronger than women, and women are there to serve man’s will. These beliefs often contribute to violence when a woman exercises her autonomy (let us recall that Rusiņš started harassing Iveta after she left him, a fact he was not pleased with). From this, it follows that combating gender stereotypes, one of the goals of the Istanbul Convention, should be part of the strategy for combatting violence. It also becomes clear why the term “gender” is necessary: it simply emphasizes the socially contingent nature of these stereotypes. Thus, it is not some manifestation of Western “gender ideology”, but simply a word that gets to the heart of a problem we all want to solve.

Jānis Grasbergs, representing the opposition party Nacionālā Apvienība (eng. National Alliance) says that violence is not related to stereotypes, but instead stems from personal “weaknesses” like alcoholism and gambling. It seems that for Grasbergs, violence against women is not a structural problem, but instead just a manifestation of other ills of individuals. It is not hard to see why Grasbergs opposes the ratification of the Convention. Although transphobia and fears of Westernization confound the problem, at the heart of the opposition to the Convention is the very simple fact that, to many opponents, there is no reason for it. As opponents repeat, violence is already illegal. If the problem does not have a structural cause, why bring in a structural solution, no less one that introduces concepts like “gender” that are foreign to the Latvian audience?

Still, the facts are clear – Latvia has the highest share of women who suffered intimate partner physical and/or sexual violence over their lifetime among European OECD member states at a stark 25%, and while data is not available for all countries, Latvia certainly harbors one of the highest femicide rates among European countries as well. While the scale of the problem sometimes got lost in more ideological discussions, the tragedy of Jēkabpils roused enough public pressure and gave Members of Parliament no other choice but to act.

Previously, threats to cause serious bodily harm and to commit murder, as well as stalking, were punishable by short-term imprisonment (up to three months), probation supervision, community service, or a fine. But with a unanimous vote, the possible punishment for these crimes was increased to 1 year in prison, and up to 3 years if the crime is done against a family member or intimate partner. Punishment for cruel or violent treatment of a person that causes physical or mental suffering, if the person is a family member or intimate partner, was also increased, with fines or community service no longer permissible means of punishment.

Finally, the Istanbul Convention was also ratified. The five-hour-long debate before ratification set in record the disagreements already outlined above. Ingmārs Līdaka, a member of Apvienotais Saraksts (eng. United List), after airing his family arrangements – “while I chop wood, my wife washes the dishes, while I fix the tractor, my wife irons the shirts. I’m a bit scared to offer my wife a more modern division of roles in the family” –, summarizes the anti-ratification position succinctly: “violence against women is not caused by stereotypes, but by behavioural pathology”, as he puts it. Meanwhile, Jana Simanovska from coalition party Progresīvie (eng. The Progressives) proclaimed her support for the Convention: “[..] I would say: women want security. And the adoption of the Istanbul Convention is a public statement that women’s security is important. (Interjection: “And men’s?”)”

As the murder of Iveta approaches its second grim anniversary, much has changed in Latvia. Numerous amendments to legislation aimed at better protecting victims of violence have been enacted. Late last year, the government accepted a comprehensive plan to prevent and combat violence against women and domestic violence in the next four years. Public awareness of gender-based violence has taken a step in the right direction, and law enforcement is quicker and more decisive in its actions. Nevertheless, the discussion that arose around the Istanbul Convention makes us question whether regulatory reform is sufficient for addressing the widespread misogynistic stereotypes that still serve as justification for cruelty.

The murder of Iveta became a battleground for conflicting worldviews. Commitment to women’s rights prevailed. Let us hope that further progress will occur without such a tragic catalyst.

Other posts that may interest you:

- New Semester, New Projects: Discover the New Student Initiatives

- Police Action, General Assemblies, Online Arguments – What Happened on March 21?

- Your Guide to the March 12 Blockade

- What’s Up With the Clocks on Campus?

Discover more from The Sundial Press

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.