Illustration: Sévérine Peyron

“In spite of my profound disagreement with the authoritarian political system of Chile, I do not consider it as evil for an economist to render technical economic advice to the Chilean government, any more than I would regard it as evil for a physician to give technical medical advice to the Chilean government to help end a medical plague.” – Milton Friedman in Newsweek (June 14, 1976)

It seems popular nowadays to consider economic theories as neither good nor evil, but simply as mathematically correct or incorrect. Economics has become a prestigious science unrelated to its potential violent effects – which are usually interpreted as mere coincidences. Even our economics courses cite theories without mentioning their consequences.

I realize that courses have time limits and that some names are best left briefly mentioned, but I do not believe Milton Friedman to be one of them. His face stared back at us from the lecture screen in our Core Economics class, as a neutral economist much like any other. Although we obediently wrote down his main ideas, we did not learn about their disastrous consequences in Chile from 1973 onwards.

What should be up there, on that Powerpoint? Should we remember Milton Friedman like the University of Chicago does, as “one of the greatest economists of the 20th century”? Or should we first dismantle the idea that Friedmanite policies brought about a free Chilean society? For one, in the 1960’s, progressive Chile already had “the best health and education systems on the continent, as well as a vibrant industrial sector and a rapidly expanding middle class” says Naomi Klein in a column in The Guardian.

The United States were concerned about Chile’s policies, ranging from their trade barriers to their strong social safety net. From 1957 to the early 1970’s, the University of Chicago (Friedman’s bastion) was chosen to conduct an exchange program for Chilean economics students, in order to spread monetarist ideas to a Chile dangerously leaning towards socialism. The returning graduates went on to teach at Santiago’s Catholic University, thus creating a never-ending loop of intellectual imperialism. Despite the influence of the so called “Chicago Boys”, Chile’s politics remained a threat to its conservative military and Nixon’s United States. This culminated in the victory of the socialist candidate Salvador Allende in the 1970 presidential elections.

Allende’s nationalization of Chile’s copper mines was unacceptable to anyone sharing Friedman’s view on state intervention or US economic interests. A friendship blossomed between the CIA, the Chicago Boys, and Allende’s domestic opponents. Over 75% of the neoliberal research to reshape Chile, done by Chicago graduates and the military, was funded by the CIA. It resulted in El ladrillo, a five-hundred page economic guide containing the foundation of the soon-to-be Chilean economic policy. The ultimate goal of this three-way cooperation is best illustrated in the alleged words of Richard Nixon, found in CIA-director Richard Helms’ notes from a meeting in 1970, shortly after Allende’s election: “Make the economy scream.”

And make the economy scream, they did. First, Chile was embargoed by the US, and internally blockaded by CIA-funded truckers. Then, on September 11, 1973 Allende was violently deposed in a coup by CIA-backed forces led by Augusto Pinochet. In the weeks leading up to the event, several Chicago Boys, led by Sergio de Castro the future economy and finance minister of the junta, were busy finishing and printing El ladrillo for Pinochet’s first day on the job. Then came a screaming of a different kind, best explained by Orlando Letelier, Allende’s ex-US ambassador, in his article published in The Nation in August 1976.

“Here Friedman’s theories are especially objectionable — from an economic as well as a moral point of view — because they propose a total free market policy in a framework of extreme inequality among the economic agents involved […]”

He was murdered by Pinochet’s secret police several weeks later. His stunning denunciation of Friedmanite policies is matched with an appalling description of out-of-control prices, monopolistic wealth-concentration in the hands of foreign global corporations, booming unemployment, all this in a radical attempt to supposedly ‘cure’ Chile of the ‘parasite’ that is state intervention. He concludes his article by touching upon the fact that Pinochet’s brutality intertwines with the Chicago Boys’ Friedmanite ideas:

“While the “Chicago boys” have provided an appearance of technical respectability to the laissez-faire dreams and political greed of the old landowning oligarchy and upper bourgeoisie of monopolists and financial speculators, the military has applied the brutal force required to achieve those goals. Repression for the majorities and “economic freedom” for small privileged groups are in Chile two sides of the same coin.”

This fusion of economic violence and dictatorial repression is developed in Naomi Klein’s Shock Doctrine (2007). “The shock of the coup prepared the ground for economic shock therapy; the shock of the torture chamber terrorized anyone thinking of standing in the way of the economic shocks.” One can say Friedman’s economic goal of eradicating government spending is intrinsically linked to Pinochet’s wish to eradicate dissent.

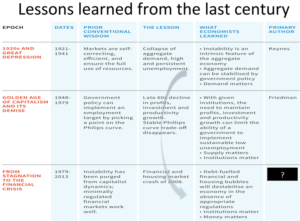

So, how can we name Milton Friedman as a primary lesson-giver of the 20th century without mentioning the practice of his ideas in the life-size nightmare laboratory of Pinochet’s Chile? For those who still doubt, let me quote Edouard Louis:

“That too, is strange, that those who should do politics are those whom politics have no effect on. For the powerful, more often than not, politics are an aesthetic question: a way of thinking, a way of seeing the world, of building your own person. For us, it was a matter of life or death.”

Source: Core Economics

Emilie Rappeneau is a French first-year Euram student from Poissy who writes for the Opinion section of The Sundial Press. She talks too much, sleeps too little and loves to write silly poems. When she’s not procrastinating, she can be found defending veganism, binge-watching Friends or playing the ukulele.

What thoughts do you have regarding this issue? Write a response by first contacting the editor, and we will publish your opinion.

Other posts that may interest you:

- Quand la sécurité prend le pas sur la liberté : les défauts du règlement Dublin

- The Pros and Cons of Effective Altruism

- An industry sewn with denial

- Rote learning is Not Learning At All

Discover more from The Sundial Press

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.