We have all been there before. We are in a foreign country having an amazing time, soaking up the local culture, eating new food, and taking in the sites. Then, the dreaded happens: someone steals your wallet, or you’re scammed into a cheesy roadside attraction, or you realize you’ve drastically overpaid for your coffee. The shame rises within you. You know what you are, but you don’t want to say it… a tourist.

Why do we shy away from the word “tourist”? It comes with connotations of Hawaiian T- shirts, disposable cameras, fanny packs and horrid sight-seeing buses. Tourists are a nuisance – they walk too slow, clutter the streets and don’t respect local customs.

Travelers, on the other hand, are sexy, cultured and adventurous. Thus, on Instagram we don’t follow “tourist” influencers, but travel influencers. We don’t read “tourist” blogs, but travel blogs. This isn’t The Sundial’s “Tourist” section, but rather the Travel Section.

However, tourism is now the number one sector of employment on the planet, with one in ten people relying on it for their income. So, let’s face it: if you’re not traveling for reasons related to work or family, you’re most likely a tourist. And when we shun this word, we do so because it makes it easier to disassociate ourselves with the uglier, more destructive sides of tourism.

For example, the negative environmental impacts associated with tourism begin on the planes, trains and automobiles you take to get to your destination. Flying usually accounts for a majority of our carbon footprint, with one five hour round trip flight being equivalent to a 60-hour cross-country car trip. Indeed, since we’ve been flying more, the problem has been growing – in the EU, CO2 emissions from the aviation industry have risen more than 80% since 1990.

But carbon dioxide emissions are not the only environmental challenge we have to worry about. There is also the issue of “overtourism” in locations that don’t have the resources or facilities to fully absorb such as mass influx of people. These are usually cities in “developing” countries or natural spots. Facility overload usually results in increased waste, pollution and destruction of resources (such as clean drinking water) in the country of destination. With natural tourism, it is not uncommon to see a degradation of the local ecology. Some common consequences of overtourism are loss of biodiversity, damage of vegetation and decreased soil porosity. This is why some destinations, such as the Galapagos Islands, have actively limited tourism so as to protect these precious natural amenities.

Another negative impact of overtourism is the local cost of living. This can sometimes be known as the Airbnb Effect, although the increase of housing prices in touristy areas has been occurring long before the creation of the app. Finding affordable accommodation in city centers is close to impossible for locals of popular tourist cities. Since 2000, the Global Real Housing Price Index, as measured by the IMF (International Monetary Fund) has increased more than 50%.

Local communities are being destroyed – grocery stores are being replaced with tourist shops and neighbors are being replaced with tourists. However, the Airbnb effect is tricky in the sense that the app allows you to pay your accommodation directly to locals instead of big hotel chains. Still, on the flip side, residents in cities with high Airbnb permeation are reporting exaggerated levels of gentrification and increased housing prices.

An Anti-Airbnb Protest in NYC, 2015. Photo: usatoday.com

Animal welfare is another issue worth thinking about when it comes to overtourism. As aforementioned, nature tourism can often result in a loss of biodiversity. However, even destinations that one may not consider to be associated with wildlife can reap negative results. For instance, close to 100 million animals are held captive annually as display, entertainment, carriers or quarried to be hunted. Less than one million of these are held in zoos.

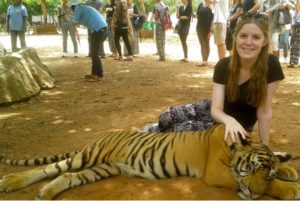

The biggest concern with their abuse extends far beyond hunting. It is not uncommon for animals to be drugged, overworked and harmed in a variety of other manners so as to engage in entertainment displays such as snake charming acts and tiger safaris.

A Drugged Tiger and a Tourist. Photo: thesun.co.uk

Lastly, crime, vandalism and nuisance constitute major problems for sites plagued by overtourism. In British culture, “stag-do” and “hen-do” trips are symbolic of this growing issue, as thousands upon thousands of drunken travelers a year descend on destinations such as Amsterdam, Krakow and Mallorca. But we cannot limit these practices to our English friends – every country is, to some extent, guilty of sending their rowdiest youth abroad.

The money brought in by this party going crowd is often outweighed by the social havoc they wreak. For instance, in November 2014 the Archbishop of Krakow urged his fellow residents of the city to join him in a month of prayer for the “spiritual renewal” of a city that had been “defaced by debauchery and drunkenness.” Outrage from locals in Amsterdam has even banned things like ‘beer bikes’, bikes that have beer on tap which rowdy tourists can chug as they peddle around town. and launch ad campaigns that demand respect from the incoming tourists who are most often drawn by the city’s lackadaisical drug and prostitution policy.

Amsterdam’s new “Enjoy and Respect” ad campaign. Photo: iamsterdam.com

The word “tourist” is ugly, but we need to embrace it in order to deal with its implications. Next time you are a tourist, do not shy away from the term and do not be apart of the problem.

Other posts that may interest you:

Discover more from The Sundial Press

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.