This piece does not engage the Opinion section of the Sundial Press and is only a reflection of the writer’s thoughts. Comments and replies to this column are welcome and encouraged by the author.

Clément Streiff

Marianne, the allegory of the French Republic, overlooks the Place de la République in Paris. ©Library of Congress

Some things in life are inherently French. The smell of croissants for breakfast, existentialism, the moody and charming sea of grey Parisian roofs, and republican universalism. Many have tried to recreate the last item on the list, but it has yet to be successfully reproduced elsewhere.

The birth of republican universalism can be seen as a beautiful story of attempting to establish equality, ending a privilege-reliant society, and giving birth to national solidarity – all set against the glorious backdrop of the French Revolution and the philosophical and ideological turmoil that came with it.

In the following text, I argue for a revision of republican universalism, which is used now as a justification for the oppression of minorities and subverts the initial Revolutionist intent of the idea.

The case for a historical revision of republican universalism

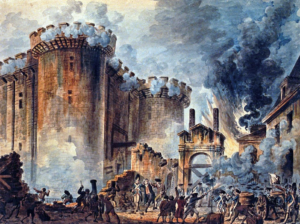

July 14th, 1789: one of the greatest dates in human history. On that day, Parisians stormed the jail of the Bastille, a symbol of absolute monarchical power. Its symbolic value is much stronger than the outcome of the day: only seven prisoners were locked up at the time of the coup, and then freed.

Nevertheless, this magnificent feat was the direct, physical embodiment of the idea of self-emancipation and represented a dramatic shift in the way that life and politics were considered. The takeover of the Bastille birthed the concept of the citizen, as well as the rights and political consideration that the political existence of such a concept would entail.

The Take-Over of the Bastille, by Jean-Pierre Houël — Bibliothèque nationale de France, public domain.

Writing about self-emancipation, I cannot help but feel butterflies in my stomach – sans-culottes butterflies that would proudly wear a Phrygian cap.

To further implement self-emancipation and equality against the State with the Revolutionist ideology, republican universalism came as a tremendous invention. By considering the citizen as an abstract product of the Nation, as a unified people regardless of religious, ethnic, and social status, one’s place within the Republic was blind to one’s origins or convictions. By doing so, the Nation successfully gave to its citizens imputable universal rights that were natural and bestowed through birth (although the Revolution refused to consider women worthy of these so-called natural rights).

Republican universalism, just like the concept of laïcité, could be divided into two schools of thought. The first one, which is currently prevalent, refuses the existence of any distinctions whatsoever of individuals on a basis other than belonging or not to the Republic, sort of in a dualist style. Meanwhile, the second one, a more monist system, allows for ethnic, socio-economic and cultural differences to be acknowledged and to be given the same imputable natural rights in order to better attain that idea of the abstract citizen.

By siding with the first school of thought, France has allowed republican universalism to become an excuse for an inegalitarian society that only benefits the elite.

Today’s republican universalism is a tool for oppression

Thinking about the state of my country today, I feel mostly anger and discomfort. The widespread hate against our Muslim citizens, the racial violence that is plaguing France, and the growing gap between the working-class and the richest are all backed up by today’s prevalent interpretation of republican universalism. By erasing differences in citizens, France is refusing to acknowledge that systemic discrimination is taking place, and refuses either to discuss solutions to solve those problems.

“I will fight any forms of communautarisme and political Islam”, the French President stated on October 25th. If parties influenced by Catholicism such as Les Républicains or le Rassemblement National were accused of communautarisme as well, Emmanuel Macron would improve in accuracy. ©AFP

France, what did you think? Whoever genuinely believed that republican universalism was so entrenched in our current political identity that people would not see others through the prism of race? Of class? Of religion?

Perhaps only foreigners are truly able to step back far enough to accurately think of republican universalism critically. This is why I am turning to the words of the German literature theorist Clemens Pornschlegel, who wrote for the Süddeutsche Zeitung in 2007: “Universalism is hence not a solution to the exclusion that strikes Arabs and Blacks. Through its ethnocentrism disguised as the logic of reason, it is itself the very problem” (translation from German to English by the author of the article).

Would republican universalism’s problem only be its ethnocentrism? We are fortunate enough for Sylvie Tissot’s work for a more intersectional approach, a French sociologist who worked on “communautarisme,” the greatest enemy of republican universalism’s antagonism. She criticizes republican universalism for failing to recognize white male bourgeois society, which has traditionally had policy-making power, as incompatible with universalism, while the stark reality is that it is holding most of the political power.

In this way, universalism selects which communities are acceptable as long as they conform to a certain white, male, and bourgeois standard rather than an actual idea of the citizen in its abstractness. In doing so, it renders suspicious any communities that are regional, sexual, racial, social, religious, and locks them in the status of minorities.

Because of an ideology that is more ethnocentric than truly universalist, France and its elites have not only refused to acknowledge discrimination but also justified them with this interpretation of our Revolutionist intentions.

We can make multiculturalism and universalism coexist.

I truly believe it is possible to revive republican universalism and make it stay true to itself. Born from the idea of self-emancipation, I do think it needs a second chance if the citizens of our country and its elites are willing to provoke this change.

Here are two solutions to consider.

First, it needs to be understood that the natural and immutable rights of the citizen cannot be implemented without a pragmatic approach to one’s condition – be it racial, social, religious, cultural, sexual, all or some of the above. Aided by the tools of realist legalism, it would require that citizens reach self-emancipation from their condition by acknowledging rather than suppressing it, as discrimination is and will remain inevitable. Furthermore, the prevalent approach to universalism needs to be recognized as disguised ethnocentrism putting a white, male, and bourgeois elite in power.

Second, activism needs to be implemented through vocabulary. As the historian, Pap Ndiaye said, “If we want to deracialize society, we inevitably have to first talk about it.” It should not be shocking that any word that does not reflect the ethnocentric reality of those who rule us offend people and is attacked by the so-called defenders of universalism. Only when French sociology will end its awkward refusal to use the word “race” and other denominations for differences will we be able to start thinking about how to start making the Republic profitable to everyone, regardless of their condition.

Embracing a diverse and multicultural universalism, and allowing communities to exist within our Republic will self-emancipate the oppressed minorities, and only by doing so will we see first, the end of the marginalization of any bodies outside of the white bourgeois reality, and second, the realization of what universalism initially intended to do for its citizens.

Other posts that may interest you:

- The Trouble with ‘Ecocide’

- Carbon dioxide removal – hit or miss?

- Local Victories for Turkish Opposition — A Sign of Hope?

- Are France and Japan a Mismatch Made in Heaven?

- A Reflection on Dark Tourism

Discover more from The Sundial Press

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.