This article is part of our collaboration with International Policy Review at IE University. You can read the other articles in the series at the link just above.

Illustration Credit: Signe Wilkinson, Washington Post

By Esra Püren San. Edited by Souane Mazou-Houel.

I particularly enjoy comedy sketches close to elections. Their satirical nature amplified with the stereotyping of opposing political actors and party members, delivers a new layer of insight.

Not simply because I enjoy good comedy material, but because it plainly and simply puts forward how we perceive the opposing side. Which of their characteristics scream at us, what kind of mannerisms are repetitive, the labels we assign to them, and most importantly, in what context certain words are employed.

The charged landscape of American politics is abundant in repeating words — freedom, security, progress, and as of the 2020s, bodily autonomy. As common as these words are in the headlines, as divergent their context and connotations became, they are all moulded by each party to fit their worldview.

This divergence creates an almost unbreakable communication barrier. Each side’s narrative is fortified by personal and religious values, as well as assumptions the opposing party neither fully grasps nor accepts. Albeit the two sides speak to each other in the same language, in every heated debate, neither speaks the other’s language. Whenever I encounter such scenery, my mind keeps tuning into the same sentence.

All language is but a poor translation. – Franz Kafka

This begs the question: is there a creeping, hidden gap in our communication? The same notion, as we encounter it in different political narratives, albeit in the same language, form differing contextual meanings, leading our translation of notions into the same language to carry a certain degree of alteration in their contextual meaning.

Such questioning is essential when we handle political communication. Looking at how the same words were employed to create divergent narratives, and therefore divergent understandings, is the Gordian knot of political communication, one that might be employed to become the most cunning tool—Rallying, or swaying thousands.

There are two chief factors which allowed a bi-polarised society to become a wildfire in 2024 from the kindling it was in 2016. The rise of antagonism of the other bubbled from resentments, and our mere anatomy. The latter has no remedy but ways of navigation. Whereas, the former is the product of the latter’s meticulous employment.

Antagonism in Political Narratives

The progressive and conservative narratives have a common ground: growth as a prerequisite for prosperity and independence, and advancement through production and consumption of commodities and services.

On this common ground, the two narratives employed powerful and antagonistic values towards one and other: freedom and equality against the risk of tyranny for Democrats, giving power back to the people by making the unknown prohibited for Republicans.

In their essences, each side promises safety and security to their supporters, and, by extension, to the nation. Democrats’ narrative finds the source of safety by promoting equal rights and income equality to the people, by generating an environment in which all people, their life choices familiar or unfamiliar to our own, have the same freedoms to build a life. Republicans’ narrative, on the other hand, locates this safety in familiarity, — and familiarity can almost always only be maintained if the unknown or different is prohibited, and cut out.

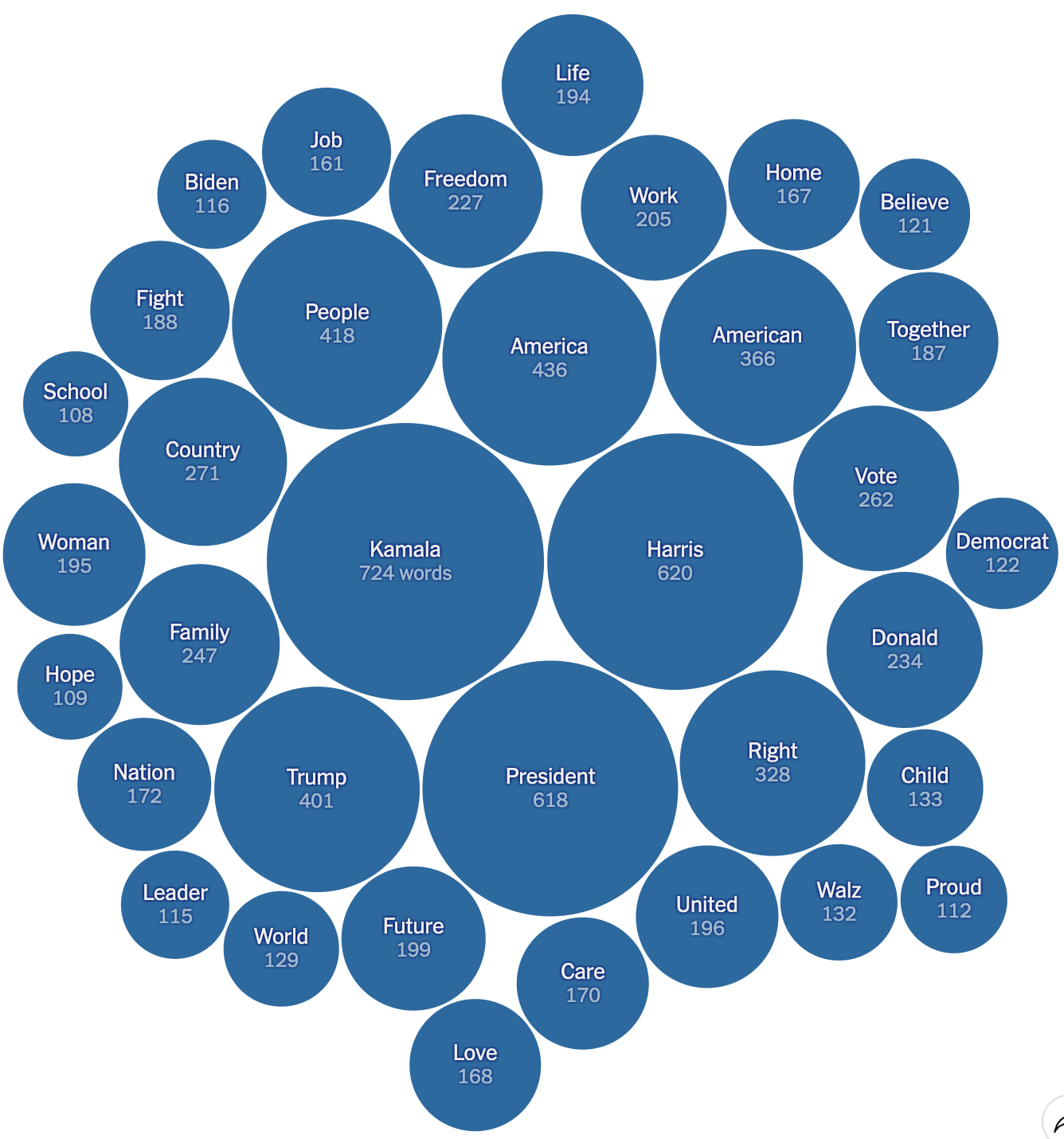

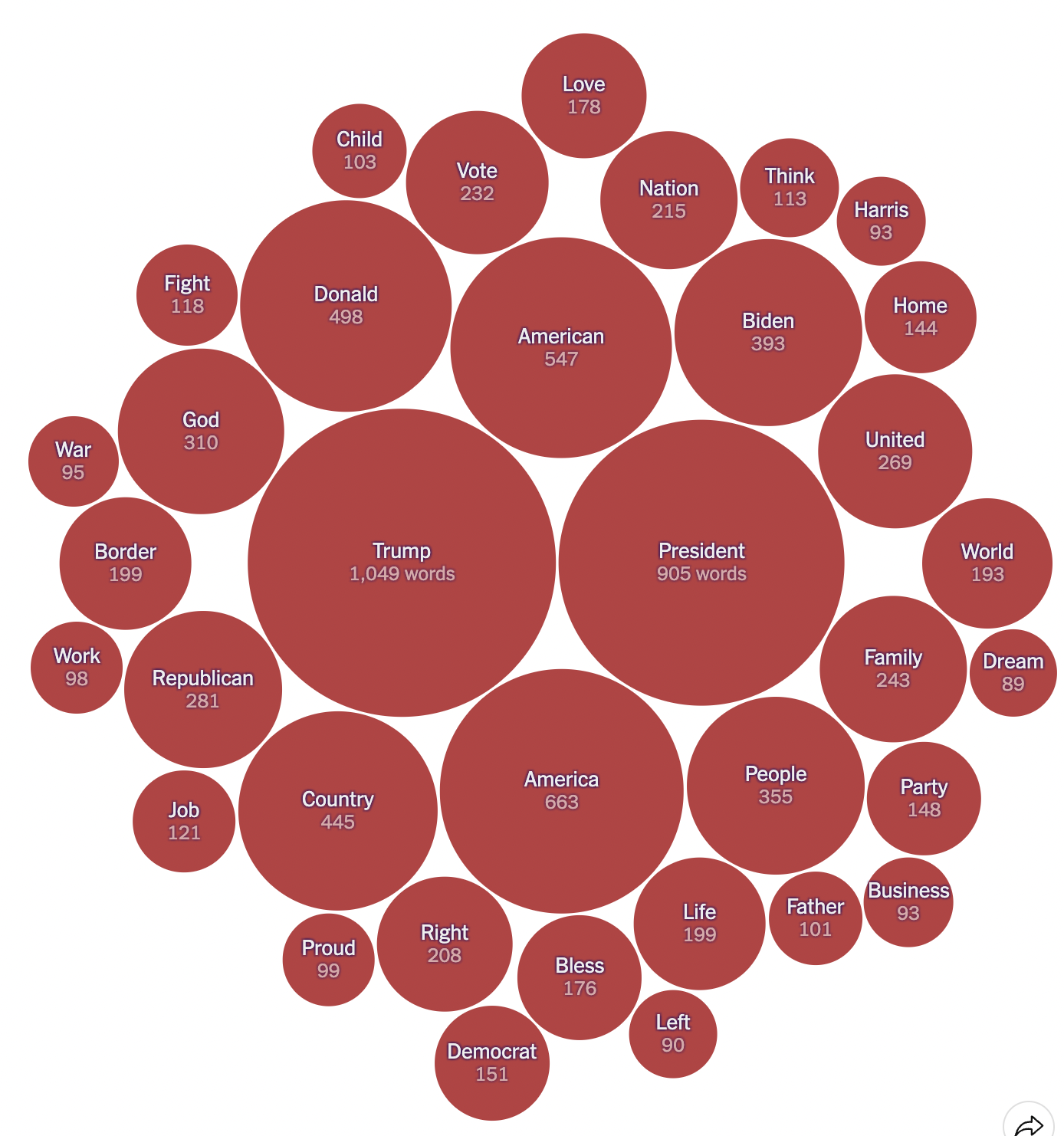

Both narratives talk about the same notions of safety and security. However, how those states are felt by their supporters paint entirely different pictures. This distinction can be seen when looked at the words used at the Democratic and Republican national conventions.

The words used at the Democratic National Conventions convey a message of growing together, a growth sustained by expansion of hope, care, and freedom to be. Whereas the words of the Republican National Conventions communicate sustain and maintain, a growth achieved by protecting — the values, societal structures and order (Family, God, Border), and freedom to stay as is.

The creation of these realities, albeit divergent from each other, is what a safe and secure future looks like for the parties’ supporters. Therefore, both parties include in their narratives the same words of safety and security and promise them. Yet, what is meant by those identical words, and what they entail needs to be done to achieve them are entirely divergent from each other.

Consequently, both the Democrats’ and Republicans’ narratives construct frameworks that feel fundamentally safe to their supporters whilst appearing threatening to the other side. In their quest to secure voters and implement their agendas, both sides contribute to the creation of mutual antagonism. This joint antagonism fosters a polarised landscape where each side seeks validation within their camp — eliciting a race to see which of the divergent futures will be built . In this divergence emerges a bi-polarised society.

Beneath the surface of such societal dynamics, another fracture starts taking shape. One that highlights disparities not only in political beliefs but in social identities, leading to the emergence of sharper factions: us versus them.

Tale As Old As Time: The People vs. The Elite

As these divergent political narratives pull people into opposing camps, an us versus them mentality takes hold of how the sides view each other’s worldviews, fuelled by an instinctual pursuit to belong and distrust of the other..

In this environment, the division between the opposing camps becomes acute, amplifying tensions between those who feel represented and those who feel marginalised, resulting in the distinction between the people and the elite. However, neither the people nor the elite are two definitive groups. On most occasions, the elite represents the 1% whose wealth equals that of the remainder of the people. However, when the first person to reach a net worth of $300 billion, and wealth of $304 billion, making him the only member of the $300 billion club according to Forbes, stands next to the leader of the people—and current president-elect— in the campaign trail, such a line gets blurred.

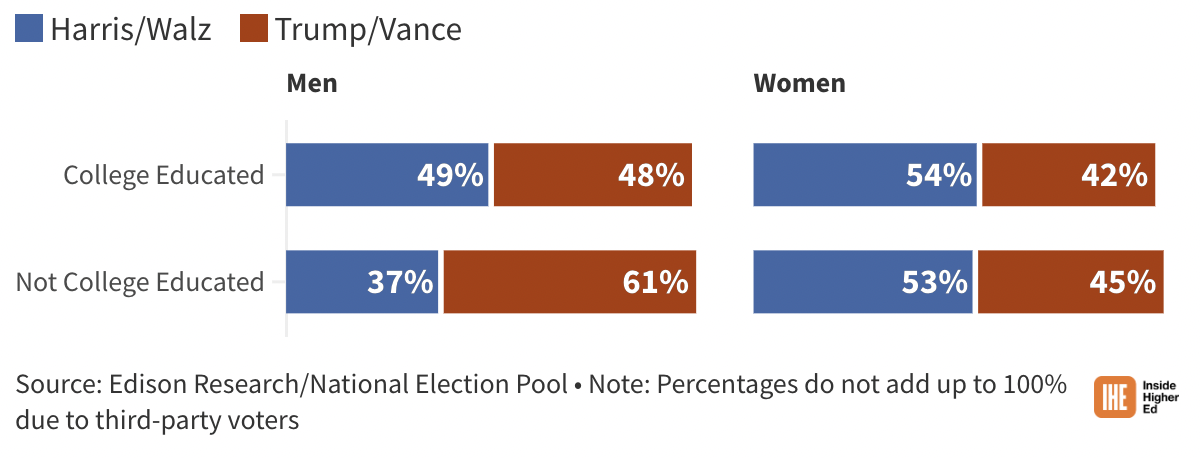

Amidst the 2024 campaign, and arguably at the crux of all recent clashes between Democrats and Republicans, the distinction between the people and the other is defined by education. This is not intended to categorise one party as more intelligent than its opponent, but rather to illustrate the disparity in educational backgrounds, and consequently, the extent of exposure to a certain expansion of knowledge and breadth of information beyond their lifelong familiarity.

Aside from having two separate titles, the two graphs are remarkably similar. To further analyse the correlation, the results of the 2024 presidential election were as follows:

It is indisputable that the level of education is a divide between party supporters. However, has such a divide simply shaped preferences, or has it transformed into a deeper rift— creating a social cleavage of two sides, the people, and the elites?

For many Democratic Party supporters, formal education fosters values that align with progressive ideals. Whilst for many Republicans, it’s often a lack of exposure to these institutions and their teachings that cement a more traditional and close-knit worldview. Education has, therefore in essence, become a greater delineator of political identity, more than just swaying party lines.

In this election, education delineated a schism between two American identities: the ‘elite’ values cultivated in educational institutions whose fundamentals are rooted in scientific rationale, advocating for social causes and equality, contrasting with the populist beliefs held by those who feel marginalised by this broadening of perspectives and changing values. In a society that was split over notions of security, freedom, and identity, education has served as both the lens and the chasm that deepened this cleavage, solidifying two sides: the elite, and the people.

The cleavage between the people and the elite is a tale as old as time. In recent years, and especially amidst the recent election however, this new divider, education and its institutional values, successfully fuelled resentments. Under such circumstances, resentment of the other becomes a great comforter, enabling one to stay loyal to their designated side. This resentment, charged by socio-economic imbalances and contrasting life experiences, fuels this factionalism. One that pits the people against the elite in the ongoing struggle over whose America will prevail.

Currently, it became a familiar America, wary of unfamiliar change, that casted the winning vote — reminding us that the pull of nostalgia, and comfort, can be stronger than the push for progress.

Why Education as a Strategy Failed

Here the principal issue remains: if the lack of exposure to educational values was the divider, then why has Kamala’s effort to educate the people, on issues ranging from bodily autonomy to both national and global economy, failed?

Two reasons: human conditioning, and the time frame.

There are many aspects in which human conditioning comes into play when the discussion leads to voter behaviour and party loyalty. The first aspect to inspect is how people make progress. Our societies on a greater level are team-based. Whether this concerns sports, entertainment or even science, humans make progress through organisations. Especially through collections of people connected by a shared vision fuelled with purpose, and belief.

This makes teamwork, being part of a collective group, the prime mover and amplifier of advancement. At our core, whether for biological needs or psychological reasons, we all seek to belong. And the main-driver of such collaboration? Us-versus-them thinking.

This urge to belong merged with the presence of a shared enemy intensifies the psychological experience of cohesion and identity, resulting in greater performance. However, such amplification of solidarity and performance is a double-edged sword.

This urge to belong merged with the presence of a shared enemy intensifies the psychological experience of cohesion and identity, resulting in greater performance. However, such amplification of solidarity and performance is a double-edged sword. If the direction of performance is for advancement, an acceleration towards it is observed. If the direction of performance is deleterious, this is where the sword goes inwards and outwards towards mutual detriment.

An infamous example of how easily, and swiftly, we might yield to our psychological makeup and get caught in mutual destruction was demonstrated by Philip Zimbardo in his Stanford Prison Experiment. Although the experiment is chiefly employed to showcase the environment’s influence on behaviour, it goes deeper to examining topics of attitude change, cognitive dissonance, persuasion, cults, and shyness.

Overall, the experiment demonstrates two key insights. First is how when belonging to a group, people are capable of blurring their personal lines of moral and immoral to contribute to the greater identity of the collective. Second, if the environment allows and the other group prevails stronger, the victims will also accept their role in shyness. In being the dominant group, the performance gets amplified, gradually, for good or evil. In shyness, grows resentments – resentments that become rooted and potent.

It isn’t suiting to allocate which party occupies which side as it is entirely interchanging, from elections to social issues. The central aspects are to recognise the grouping mentality with its effects and strength, and growing resentments in the shadows.

When a group’s performance to achieve their collective identity starts getting accelerated for detrimental results, from the outside the dangers are visible. However, from the inside much less so. This was demonstrated with the divergent public opinion and sentiment with the overturning of Roe v. Wade, and the issues surrounding women’s right to their bodily autonomy. Whilst one group saw it as a victory, getting them closer to their America, the opposing one voiced its detrimental repercussions.

Under such dynamics, trying to educate a side out of their victory is not a suitable strategy for the short-run. There is a wide range of powerful emotions of pride, success, and victory attached to this decision from their perspective amplified with grown resentments. And against such strong emotions, education and data are no winners for the first rounds.

If you ever came across a skilled salesperson or had the necessity to take a sales class, you’d know the first rule of selling doesn’t rest on how well you inform the interested party. Rather on how well you connect, and tickle that je-ne-sais-quoi in them that consequently leads you to a sale. This is to say, collectively, in most sales and decisions, emotions powerfully, predictably, and pervasively influence decision making. And isn’t a presidential campaign the biggest sales campaign there is?

Is a Common Language At All Possible

Is this all to say a common language is lost in translation or are we yet to learn it? A common language, in theory, should be the natural bridge to connect divergent perspectives. Yet, language alone is insufficient when its meanings are shaped by fundamentally differing values, experiences, and worldviews. The clash is the context the languages carry — context often so deeply rooted in identity that they resist external challenge or reinterpretation.

For a common language to emerge, both sides must first recognise the common grounds their opposing views share and are built upon, and where and why they diverge. This requires adapting a certain degree of education aimed for the long run. An education that is, as far as it can be, clean from false information and grand political narratives that dilute evidence and cloud judgments.

This requires an intentional effort to step outside of entrenched narratives and recognition of the opposing sides fears and resentments, not to erase differences but to reframe them as complementary rather than antagonistic. Such a shift from the us-versus-them mentality cannot be achieved through simply imposing education in the short period, as human behaviour and our decision-making mechanisms are far more influenced by emotion, identity, and a sense of belonging.

This communication must appeal to the emotions and the instincts by not only telling people the repercussions but by showing them what the ripple of misinformation and negligence has caused so far, and will continue to generate. If effectively communicated, the notion that the absence of adequate knowledge to inform our judgements is more detrimental to individuals themselves, prior to society, than being driven by resentments and inherent desires, people will have a reason (and self interest) to listen. However, if the communication is transmitted in a way that the information is coming from a self-appointed superior point, it will be received neither as beneficial nor altruistic, or even be heard.

Bridging this gap is possible, but it will demand leadership that prioritises connection over division and messaging that appeals to shared aspirations as well as one that recognises the fears and resentments of the opposing side — not to exploit them to sway votes for one campaign or two but to minimise the gap in communication and understanding. Until then, the language of American politics may remain a conversation of parallel monologues — coherent within each side but unintelligible to the other.

Other posts that may interest you:

Discover more from The Sundial Press

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.